Aged tombstones and new burial markers, a wrought iron arch and the Avenue of Oaks make up Winchester Cemetery, above. The burial grounds, northwest of La Grange, were donated in 1871. Sarah Beal photo

On the Bluebonnet region’s roadsides and buildings, historical markers tell the stories that shaped our past.

Stories by David Pasztor l Photos by Sarah Beal

You see them standing sentinel on roadsides, gracing courthouse lawns or hanging on aging buildings. Across the state, thousands of historical markers tell small pieces of the story of Texas. Some were erected by national or local historical organizations. Many more are the work of a program run by the Texas Historical Commission.

They are whispers on the landscape, capturing pieces of the past — poignant, mundane or monumental — and tracing the evolution of a land, its towns and people. The plaques are reminders of the founders, fighters, builders and worshippers who passed through not so very long ago. They remind us that it is important to stop sometimes in our busy days and learn more about the treasures of the Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative region’s past.

Texas started placing historical pins in its map not long after it was formed. In 1856, gravesites at the San Jacinto battleground near Houston were commemorated 20 years after the decisive fight that won Texas its independence from Mexico. By 1936, the Texas Centennial Commission erected more than 1,100 markers and monuments around the state. The Texas Historical Commission began its official program in 1962 and has since placed more than 17,000 cast aluminum markers statewide.

Each of the state’s 254 counties has at least a few. Here is a sampling of the stories behind historical markers in counties and towns in the Bluebonnet region.

WINCHESTER CEMETERY

Fayette County

About half a mile east of Winchester on FM 153, a wrought iron arch welcomes visitors to a cemetery with historical threads deeply woven into this small community northwest of La Grange. Col. Nathan Thomas, a former Republic of Texas congressman, donated the land for the burial grounds in 1871. It became the final resting place for many of the area’s original settlers and is still in use today.

Winchester hit its peak in the early 1900s, shipping local cotton and other farm products while the town was a stop along the San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railroad. The town boasted 18 businesses in 1900, but the number dropped to a handful after 1950.

Winchester remains a picturesque small town, and many descendants of former residents are still being buried in the carefully maintained cemetery. In 1999, an “Avenue of Oaks” was planted along the main entrance, and in 2002, nine Victorian-style lamps were installed around the grounds to provide light and security.

BURTON FARMERS GIN

Washington County

When it was built around 1914, the Burton Farmers Gin was a marvel of cutting-edge technology, a steam-powered integrated system that could “process cotton from wagon to bale in a continuous operation,” according to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers. The gin, one of four in Burton, could turn out seven bales per hour.

It was the last gin in Burton by the time it stopped operating in 1974, as the importance of the area’s cotton waned. But fans and preservationists have been able to keep its unique machinery and structure intact, and it’s one of the few gins from that time that can still operate. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Burton, a small town on U.S. 290, 22 miles east of Giddings and 13 miles west of Brenham, continues to embrace its history. In addition to preserving the gin, the town is home to the Texas Cotton Gin Museum. The historical marker is attached to the old gin at 307 N. Main St. For more information, call 979-289-3378 or visit texascottonginmuseum.org.

THE DR. EUGENE CLARK LIBRARY

Caldwell County

One of the most storied buildings in downtown Lockhart is also the perfect place to sit down with a good book. Just off the town square, on South Main Street, the two-story Dr. Eugene Clark Library is an architectural showpiece of red brick and limestone that is the oldest continuously operating library in Texas.

Clark, a New Orleans native who practiced medicine in Lockhart for 13 years, died in 1897 at age 37. On his deathbed, he “dictated a will specifying that the citizens of Lockhart should have a library and lyceum,” according to the City of Lockhart’s website. “His will left $10,000 to the people of Lockhart, of which $6,000 was to be used for construction, $1,000 to buy books and the remainder was to be put in a trust to maintain the building and purchase new books.”

Dedicated in 1900, the library has endured as a social and cultural hub for Lockhart. The building alone is worth a visit, but after expanding into an adjoining building, it also remains a fully functional, modern library, where people can go to fulfill their desire to learn.

THE CHISHOLM TRAIL AND EL CAMINO REAL

Burleson County

Two legendary paths through Texas history cut through Burleson County near Caldwell, and they are enshrined on historical markers a few miles apart on Texas 21.

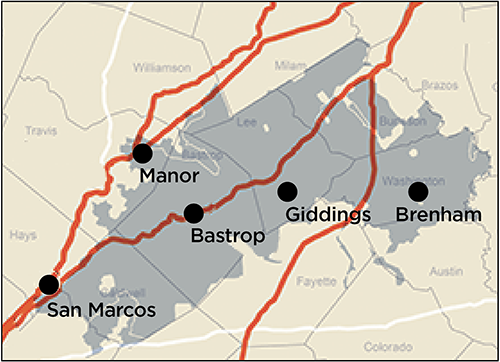

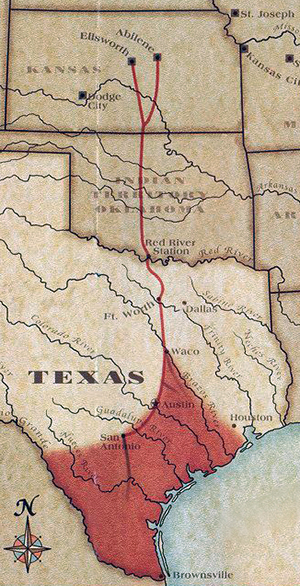

After the Civil War, between 1867 and 1884, the Chisholm Trail became a major thoroughfare for longhorn and other breeds of cattle headed to Kansas for sale. The trail started as many smaller trails, with many names, in far South Texas. Named after the merchant Jesse Chisholm, who established it in 1865, it eventually stretched at least 800 miles. One of those branches ran through Burleson County, as well as six other counties now in the Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative region. “The trail became a significant commercial road. Vital to the development of Burleson County's cattle industry, it declined in use after rail lines reached the area in the late 1870s,” according to the marker on the north side of Texas 21 about 8 miles west of Caldwell.

Many stretches of Texas 21 also follow the path of another storied trail: the original El Camino Real de los Tejas — the “royal road of the Tejas,” or Caddo Native Americans. Paths that had been formed over hundreds of years by the passage of indigenous peoples and bison became the primary trade routes for Spanish colonization from 1690 to 1821. The historic trail stretched 2,580 miles in the United States, starting in colonial Mexico City, crossing Texas and ending in Louisiana. Three branches of El Camino Real in Texas crossed large segments of today’s Bluebonnet service area. The National Park Service, which named it a historic trail in 2004, said El Camino Real was “instrumental in the settlement, development and history of Texas. Its path, parts of which are now paved by major highways, including Interstate 35, was key to the growth of several cities, including San Antonio, Austin, San Marcos and Bastrop. The Burleson County historical plaque is on the south side of Texas 21, near the turnoff to Dime Box.

WEBBERVILLE EBENEZER BAPTIST CHURCH

Travis County

Where the Colorado River loops north on the eastern edge of Travis County, the community of Webberville is directly in the path of growth and development pushing out from Austin.

But in the early days of Texas, it was an isolated refuge where John F. Webber, a white man married to a Black woman, moved his family in 1839.

The town that grew here took Webber’s name. It was first called Webber’s Prairie, according to the Texas Historical Commission. But his family did not find the peace they sought, and in 1851 Webber sold his land and moved to Mexico.

After the Civil War, the community began to evolve. “In 1868, Matthew Duty donated one acre of land here for the purpose of building a church for the area’s recently emancipated African Americans. That year, the Webberville Ebenezer Baptist Church was organized. Duty, a resident of Webberville, is commemorated on the marker, which is at 1314 Weber St. off FM 969, directly in front of the church. Surrounding the marker is an open pasture and an iron fence enclosing several stone markers, known as Duty’s Cemetery, where Matthew Duty and several of his family members were buried in the 1800s. The site is between Webberville Village to the north and a Dollar General to the east.

“Ebenezer Baptist remains active despite the relocation of many of Webberville's families to nearby urban centers. Former members continue to gather here on special occasions and holidays,” reads the marker.

DIME BOX

Lee County

The story of Dime Box actually started about 3 miles from where the town now sits on Texas 21, 18 miles northeast of Giddings. Originally, Dime Box was built in the 1860s and early 1870s when Joseph S. Brown built a sawmill. It got its name because residents would leave dimes, letters and orders for small items in a large wooden box for a mail carrier on horseback to take to nearby Giddings. The mail carrier would return with residents’ mail and items, which were dropped in the box.

In 1913, the Southern Pacific Railroad built a line about 3 miles south of the original Dime Box, so most residents and businesses moved nearer to the railroad. The new site claimed the name Dime Box. The original location along Texas 21, now known as Old Dime Box, is still home to some residents. The wooden box was probably used for only a few years, but Dime Box’s 207 residents continue to honor its story of origin. The town received national attention in 1946, when a CBS radio broadcast kicked off the March of Dimes fundraising drive from Dime Box, according to the Texas State Historical Association.

A historical marker on FM 141 near Stayton Avenue partly captures the town’s past, but a little farther down the road is an actual “Dime Box,” a 2-foot replica of a dime encased in a large transparent box. Nearby is the Dime Box Heritage Museum, which holds crafts and quilts from the area’s German and Czech settlers.

EDUCATION IN INDUSTRY

Austin County

In the 1830s, German immigrants began settling in Austin County about 14 miles southwest of Brenham. They founded the town of Industry, believed to be the oldest German settlement in the state, and brought the idea of free public education from their home country.

By 1880, the county had established a system of public schools, including five in Industry. Local education advocates also tried to establish a college in the town, although the plans never came to fruition. Blinn College, the closest institution of higher education, is 14 miles away.

Over time, Industry’s fortunes ebbed with the decline of cotton farming. The local school district was eventually absorbed by the nearby Bellville Independent School District. But education remains a cornerstone of the farming community: The West End Elementary School in town still serves 168 local students, and the historical marker capturing the town’s history stands in front of the school on FM 109, about half a mile south of downtown.

BARON DE BASTROP

Bastrop County

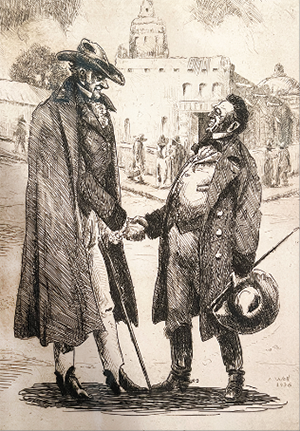

Two markers in Bastrop memorialize the city and county’s namesake — Felipe Enrique Neri, Baron de Bastrop, a major figure in the colonization of Texas.

The markers describe him as an empresario and land commissioner. The largest marker, hewn of granite and metal in 1936, is on the northwest corner of the Bastrop County Courthouse grounds, near the intersection of Pine and Water streets. It reads, in part: “Let this name bring to mind the friend and advocate of the pioneer in a foreign land.” The second marker is on the grounds of Bastrop State Park, about half a mile east of Loop 150 on Park Road 1-A.

The markers tactfully omit the self-styled baron’s backstory, a tale of how the ambitious and desperate once looked to the fledgling Texas territory as a place to reinvent themselves.

Born Philip Hendrik Nering Bögel in 1759 in Dutch Guiana — now Suriname in South America — he moved to Holland with his parents as a child. He left about 30 years later, fleeing a bounty for his arrest after charges of embezzlement of tax money, according to the state historical association’s Handbook of Texas.

Bögel changed his name to Neri, added a flourish with the title of baron and headed to the United States. He passed through several states before arriving in Texas, where he became instrumental in helping clear the way for colonists.

“Although his pretensions to nobility were not universally accepted at face value even in his own lifetime, he earned respect as a diplomat and legislator,” the handbook notes. He died on Feb. 23, 1827. Friends and fellow legislators paid the cost of his burial in Saltillo, Mexico, which was then the capital of a vast region that included Texas.

CEMENTERIO DEL RIO

Hays County

Here’s the trick to finding this well-hidden but precious historical gem: Take Texas 80 east out of San Marcos and turn right onto FM 110, also called Old Bastrop Road. (There’s a light at the intersection.) After crossing the San Marcos River, immediately look to the left for a small, hard-to-spot gravel ranch road. Follow that path to its end.

There you’ll find the Cementerio Del Rio, a burial ground that hasn’t been used for at least 80 years but still speaks volumes about the multicultural history of San Marcos and Central Texas.

The three-acre cemetery on the south bank of the San Marcos River sits close to the old location of the Spanish settlement of San Marcos de Neve, which was authorized by the Spanish in a bid to stop Anglo expansion in the area. Hit by floods and conflict with Native American tribes, the settlement lasted only from 1808 to 1812.

In 1893, the site was deeded to Hays County “for the purposes of a church, school and Mexican-American burials,” according to the historical marker on the cemetery grounds. It’s hard to say how many people are buried there. Many tombstones are faded beyond readability or toppled and decayed from decades of exposure to the elements.

Grave markers that can be made out are mostly in Spanish, with burial dates ranging from 1906 to 1941. “A majority of the surviving stones which are mainly from 1910-1920 reflect the influx of Mexican immigrants around the time of the Mexican Revolution, thereby exhibiting the growth of a unique culture in San Marcos,” the historical plaque notes.

About Texas’ historical markers

Thousands of Texas Historical Commission markers are scattered across Texas, and as of mid-September, 2,169 of them could be found in the 14 counties where Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative provides electricity. To explore a complete list of these markers, visit the commission’s website at bit.ly/4d58AG9, which includes an interactive map and search features.

Each marker highlights significant people, events, structures or locations that have been a part of Texas’ story. The historical commission has other programs designed to protect and restore historic places, including 39 historic sites.

One site is in the Bluebonnet service area: Washington-on-the-Brazos in Washington County.

Qualifying for a historical marker requires an application, documentation of historical significance, community involvement, a review period and a nonrefundable $100 fee. Applications for Texas Historical Commission marker designations in 2025 will be available on Feb. 1, 2025, and will be accepted from March 1 through May 15. More information is here.

Sources include: Texas State Historical Association, Texas Historical Commission, National Park Service, El Camino Real de los Tejas National Historic Trail Association, U.S. Census Bureau; additional reporting by Ed Crowell

Download this story as it appeared in Texas Coop Power magazine »