Purple horsemint Other common names: Lemon beebalm, lemon mint, plains horse-mint, lemon horsemint, horsemint, purple lemon mint Scientific name: Monarda citriodora Characteristics: Annual herb that grows 1-2 feet tall and displays lavender-to-pink tufted flower spikes; when leaves are crushed, the plant emits a citrus scent; attracts bees and butterflies Water requirements: Drought tolerant

FIELD NOTES

A guide to the flora that flourishes in Central Texas

Texas plants, like Texas residents, generally come in two varieties: natives and transplants.

Despite our sweltering summers, Mother Nature has gifted us with more than enough native and adapted flowers, bushes and trees to keep our landscapes looking picture perfect.

Native plants, such as bluebonnets, were born here. They evolved to thrive in our heat, humidity, dry periods and sometimes unforgiving soils. The transplants — such as crape myrtle and shrimp plant — arrived from elsewhere, but got to Texas as fast as they could. Some of them have adapted so well and been here long enough that they’ve put down permanent Texas roots.

In Texas, we know that one size does not fit all. In fact, the Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative service area alone, at 3,800 square miles, is large enough to be in two of the state’s 10 “ecoregions,” as defined by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. In these regions, different soils and conditions accommodate different plants. Sun, shade, drainage and drought tolerance help determine where a particular plant will thrive.

Spring is the most popular time to get growing in Central Texas, although there is plenty to plant in the fall. To help you get started, we’ve compiled short profiles and expert tips about what grows best in the Bluebonnet area.

“Have your soil sampled so you know what you’re starting with,” said Skip Richter, a Texas A&M AgriLife Extension agent. You can buy a test online or at a local garden center for about $15, he said. Then mail in your dirt and get a report back telling you the pH (acidity/alkalinity) of your soil, its salt and organic matter content, and whether your dirt is nutrient-heavy or in need of fertilizer.

If you have alkaline soil, but are determined to plant acid-loving azaleas that grow well in states such as Georgia and Alabama, you might have to switch plans, said Lisa Blum, a master gardener in Burleson County. “I have a friend from Louisiana who wanted azaleas” in her garden, Blum said. “I recommended the ‘Encore’ azaleas because they were specifically developed to be less picky about their soil, and to do well in the heat.”

Texas’ tough conditions don’t make it easy. On top of the weather, some plants come armed, like the razor-sharp fronds of sago palm or the piercing thorns of roses. Preparing soil could call for some hard labor, and bugs (mosquitoes, fire ants) will be after you or your plants (aphids, caterpillars). Ready to roll up your sleeves?

WATERMELON: THE PRIDE OF LULING

Luling residents love their watermelons. They love eating them, growing them, and celebrating them.

Commercial watermelon production in Luling began in the 1930s and steadily in-creased until the 1980s, according to Wayne Morse, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension agent for Caldwell County. “Early watermelon growers found the Luling area had the perfect soil and climate” to grow this West African native fruit, he said.

“It’s all about the soil,” added Skip Richter, another Texas A&M extension agent. “Watermelons like a well-drained, sandy-type soil.”

During the heyday of watermelon produc-tion in the Luling area — the 1950s to the 1980s — hundreds of acres produced the large, sweet fruit, with much of it exported to Canada, Morse said. Finding laborers to harvest the fruit became increasingly difficult, and watermelon-craving feral hogs cut into the yield. Although production has decreased, the fruit remains an important part of the city’s history and culture and is a favorite at farmers’ markets and roadside stands, according to Trey Bailey, executive director of the Luling Economic Development Corporation.

The annual Luling Watermelon Thump, which has been held at the end of every June since 1954, continues to draw about 30,000 revelers for food and entertainment. The four-day celebration is the site of the world-champion seed-spitting contest. Plus there's the parade, presided over by the Thump Queen, a high school junior who is elected by residents.

Best picks: Watermelons to grow in Central Texas

• Black diamond (red flesh, sweet)

• Crimson sweet (crisp, fiberless)

• Charleston gray (juicy heirloom)

• Bush sugar baby (flavorful)

• Jubilee (crisp, flavorful)

FOR THE LOVE OF LOBLOLLY

Among the most revered plant life in Central Texas are the loblolly (Pinus taeda) pines of Bastrop County. These towering evergreens can reach 100 feet but typically top out at 50-80 feet tall with a trunk about 3 feet wide. They are fast growers, shooting up about 2 feet each year. They can live more than 150 years.

The “lost pines” of Bastrop are a testament to nature’s adaptability. The swatch was once part of a vast expanse of pine trees that covered much of the southeastern United States, including much of East Texas. As the Texas climate became drier over thousands of years, the territory of these pines shrank.

But Bastrop’s sandy and gravely soils, including a subsurface layer of water-preserving clay and plentiful aquifer-fed springs and seeps, allowed the trees to thrive. They gradually adapted to require 30 percent less rain than loblollies in East Texas and adjacent states. The Bastrop stand has become one-of-a-kind, genetically.

“The pines add a uniqueness to our area,” said Rachel Williams Bauer, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension agent for Bastrop County.

If you’d like to help build the loblolly population by adding a pine or two to your yard, it’s probably best to buy a young sapling from a local nursery center. A 15-gallon container with a 5-foot tree can make a nice addition to your landscape immediately and then grow into a true beauty.

THE SWEET SMELL OF BRENHAM

Brenham's Antique Rose Emporium is a fragrant, lush 8-acre floral paradise that draws rose lovers from around Texas and beyond.

Antique roses are typically grown in residential yards on rambling bushes or vines. In contrast, hybrid tea roses are grown commercially, perhaps for inclusion in this month’s Valentine's Day bouquets.

The Antique Rose Emporium was founded in the mid1980s by horticulturist Mike Shoup as a “labor of love.” A chance encounter with a spectacular rose clambering with abandon over a chain-link fence led to the enterprise that has rescued dozens of old rose varieties, giving them new life in Texas landscapes.

Antique Rose Emporium

10000 FM 50, Brenham

(979) 836-5548

antiqueroseemporium.com

“These roses were mail-ordered by early Texas settlers to enhance their gardens,” Shoup said. The people who lovingly tended their plants and the homes the roses beautified are lost to time, but nature endures. “I was finding roses that were timetested survivors for a hundred years,” he said. “You have a plant that’s the best of natural selection.”

The nursery and garden has 300-400 rose varieties for sale at any time, some originally imported to Texas. Others are Lone Star State natives. Many were first collected along roadsides or in cemeteries. “Cemeteries are fruitful hunting grounds for these old roses,” Shoup said. “They are micro-environments of what will do well in an area.”

Shoup and the Emporium team develop their own cultivars — plants bred to shine in the Central Texas heat — while highlighting Shoup’s favorite qualities: personality and fragrance. “Old roses embellish the architecture of the home. They’re so endearing,” Shoup said. “And the fragrance. You can see the tears welling up when a customer smells a certain rose smell.”

Many people are intimidated by growing roses, thinking they are fussy, Shoup said. “But they’re not. I want to dispel the myth that roses are difficult. They’re just not.”

He encourages mixing roses in your landscape with other Texas natives. At the Emporium, for example, roses are paired with salvias and ornamental grasses.

A visit to the Emporium can fill an afternoon. “I don’t mind people coming and just hanging out,” Shoup said. “That’s the spirit of a garden. That’s what a garden is for.”

Mike Shoup’s rose-growing tips

- Plant in early spring or late fall

- Plant into a mixture of existing soil and compost

- Don’t add synthetic fertilizer

- Add plenty of organic matter

- Mulch well around planting site

TEXAS ECOREGIONS

Texans like to boast about the glorious magnitude of our state, and one example is our whopping 10 ecoregions, as determined by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

Ecoregions are areas defined by distinctive geography, and uniform sun and precipitation. There are variations in climate, topography and landscapes. The state has southern subtropical areas, where palms and citrus grow, and northern temperate areas where you might see fields of daisy-like coreopsis. Some regions can get as much as 56 inches of rain a year, while others are lucky to get eight. Like Texans, our lands are diverse, too.

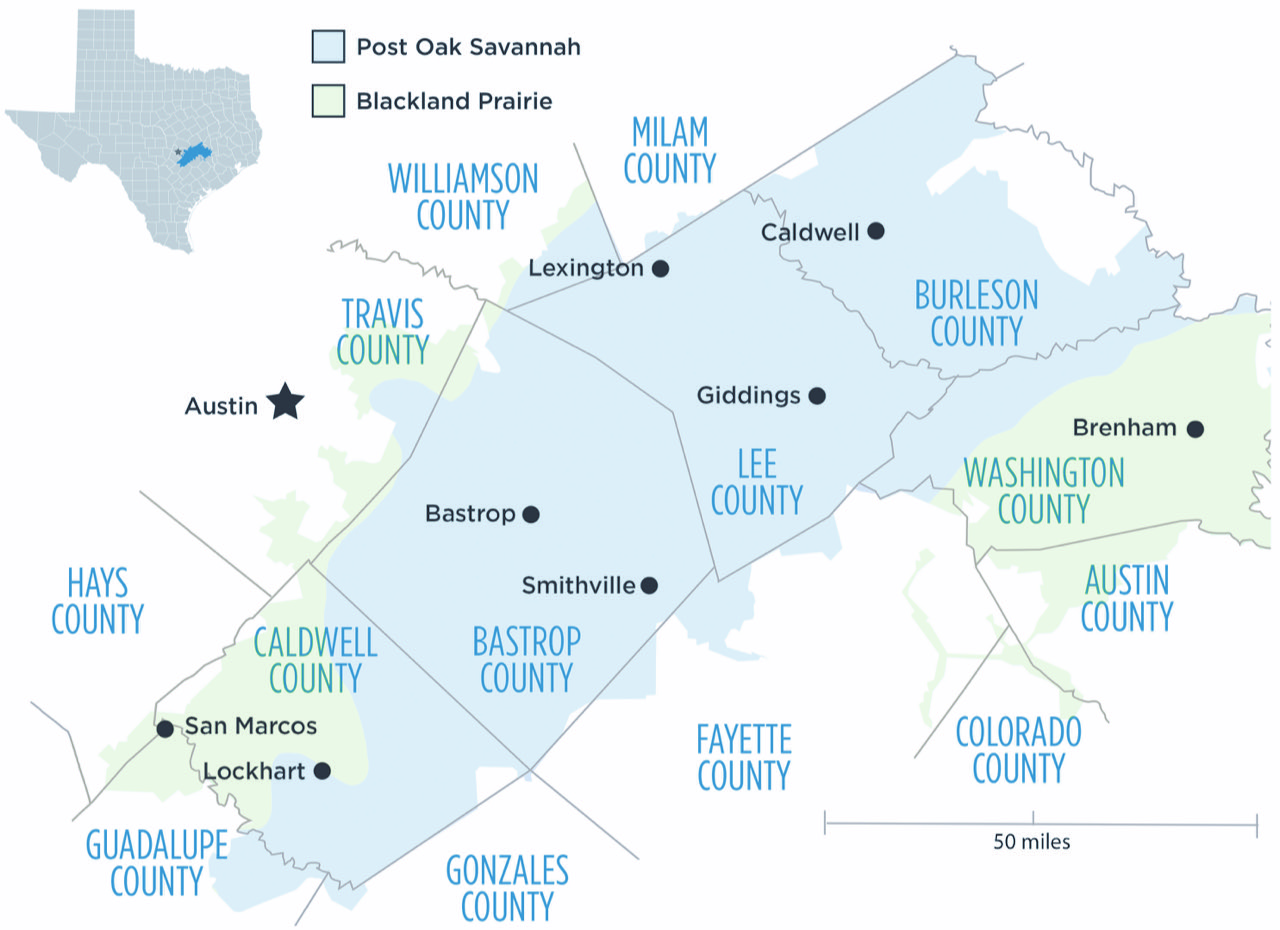

Plants that grow well in the high desert Big Bend region of West Texas — such as the spindly, spiny shrub ocotillo — likely won’t do well in Dime Box in Lee County. Most of Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative’s members are in the Post Oak Savanah region (also known as East Central Texas Plains), but much of Washington County and parts of western Caldwell County are in the Blackland Prairie region. Because these ecoregions are next to each other and have similar annual rainfall totals — around 30 inches — plenty of plants will do well in both.

Post Oak Savannah

The Post Oak Savannah region has an arid climate and dense, compact soil with a high clay content. The Post Oak Savannah is mostly gently rolling, wooded plain. The area was historically characterized by high grasses — such as little bluestem, Indiangrass and switchgrass — and wildflowers such as verbena, yarrow and winecup. Clumps of trees such as cedar elm, common persimmon, sugarberry and eastern red cedar punctuate the Post Oak Savannah.

Parts of Bastrop County are in a separate, smaller ecosystem with an unusual, native expanse of loblolly pine.

Blackland Prairie

This area is known and named for its fertile dark clay soil. Full of nutrients, Blackland Prairie soil is known as some of the richest in the world. The dominant grass of this once tallgrass prairie is little bluestem, but big bluestem, Indiangrass, eastern gammagrass, switchgrass and side oats grama can also be found, according to the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. The Blacklands are largely prairieland, but a number of trees have found a home in this region, including pecan, black walnut, sycamore, bur (or burr) oak, cedar elm and Mexican plum.

Download this story as it appeared in the Texas Co-op Power magazine »