James Harkins installs the outdoor unit of a heat pump system at a home near Elgin. Heat pump systems, which look similar to conventional HVAC systems from the outside, work by transferring heat rather than generating it, making them an energy-efficient option for heating and cooling. Sarah Beal photo

Don’t let the name fool you. Today’s heat pumps can cool and warm your home year-round.

Story by Sharon Jayson

Photos by Sarah Beal

The typical heating and air conditioning systems in Central Texas homes now have competition. Despite the name, a heat pump — more specifically, an air-source heat pump — can warm a house in winter and cool it in summer. Proponents tout the technology for its money-saving energy efficiency.

A growing number of homebuilders and buyers in the Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative service area, across Texas and throughout the southern U.S., are choosing air-source — or air-to-air — heat pumps, either connected to ductwork throughout the house, or “mini-split” systems for smaller spaces. These systems heat and cool through a single unit rather than separate air conditioning and heating components and use 50% less electricity on average.

Although savings vary by system and home size, homeowners could potentially save an average of $670 annually on electric bills with a whole-home heat pump rather than a conventional heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) system, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

Air-source heat pumps use 32% less electricity for cooling, depending on the size of the house and the temperature outside. In winter, they can reduce electricity use for heating by as much as 75%, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

There are different types of heat pumps, including geothermal systems that transfer heat between a home and the ground or a nearby water source. Those systems are more expensive to install and require underground pipes.

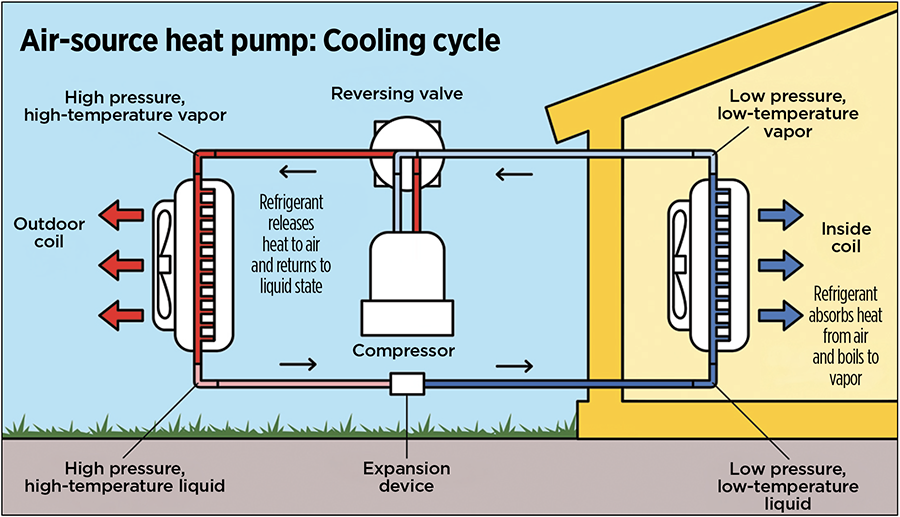

Air-source heat pumps work by transferring heat using a refrigerant that absorbs and releases heat as it cycles through the system. In winter, the pump extracts heat from outside air — even when it is cold — and transfers it inside to warm the home. The refrigerant absorbs heat energy from the cold air, and a compressor and heat exchanger release it indoors.

To cool a home in summer, the process reverses. The heat pump absorbs heat from the indoor air using the refrigerant and transfers it outside, cooling the home. The process is similar to a conventional air conditioner, but is typically more energy-efficient. The systems can dehumidify too, making indoor air feel cooler on humid days.

The smaller ductless mini-split is suited for single rooms, workshops, very small homes or additions.

In the Bluebonnet region, more builders are opting for heat pumps instead of traditional heating systems powered by electricity or natural gas.

“We’ve seen a couple of our builders in the last two to three years switch strictly to heat pumps. Some that were strictly using propane for heating are venturing out,” said Steve Honeycutt, co-owner and co-founder of Honeycutt Air Conditioning in Bellville, which serves Bluebonnet members in Austin, Colorado, Fayette and Washington counties. “Consumers themselves are asking about it.”

The average cost to buy and install a heat pump system that can heat and cool a new 2,500-square-foot home is approximately $18,000, Honeycutt said. In his service region, this is only about $1,000 more than the cost of buying and installing a conventional HVAC system.

“Air-conditioning equipment has gotten expensive in the last 10 to 15 years,” he said. Between increases in supply costs, Environmental Protection Agency regulations on HVAC systems, foam-insulated homes — which require specialized tools — and advancements in technology, the cost of a traditional system has gone up significantly, Honeycutt said.

“Heat pumps are way more cost-effective than propane heating, especially in areas without natural gas,” said Anthony Gomez, a Bluebonnet member in Cedar Creek, as well as service manager at Austin-based Strand Brothers, a plumbing and HVAC company that operates in Bastrop, Caldwell, Travis and Williamson counties.

The cost of an air-source heat pump system depends on its size and number of units needed. Other factors that affect the price are the home’s square footage, ceiling height, number of stories, insulation levels and types and the heat pump’s energy-efficiency ratings. If the pump includes special features such as higher-rated air filters or variable-speed motors to improve efficiency, that increases the cost.

One family in the Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative service area recently opted for heat pumps to cool and warm their new 2,750-square-foot home near Lexington. Eric and Meredith Middaugh and their three children — Logan, 15; Landry, 13; and Lincoln, 7 — moved into the house last August.

They moved from a larger home in Coupland in Williamson County. It also had an air-source heat pump. That convinced him of the technology’s efficiency. “I knew from experience that heat pumps are more energy-efficient and would be a great choice for our new home,” he said.

The family’s new house is equipped with two air-source heat pumps: a 2-ton unit for the bedrooms and a 3-ton unit for the common areas.

“I’ve been really impressed with how well the systems work, especially in the summer,” he said. “Our Bluebonnet electric bill for cooling was just $150 a month, even during the hottest part of the year.” In comparison, the average monthly Bluebonnet electric bill for a home that size in the summer is $215. Bluebonnet has one of the lowest electric rates in the state.

As of December, the family’s heating costs were low. “Our bills have run about $175 a month, which is much lower than what I expected for a home of this size,” Middaugh said.

Despite the new wave of interest, heat pumps have been around since the mid-1800s. For more than a century, they were used mostly for large-scale and industrial heating. The technology to both heat and cool a home was available in the 1970s, but technological advances now make them increasingly popular options for new homes or retrofitting all or part of existing homes.

James Harkins, owner of Elgin-based ACHS Inc., handled the installation of the Middaughs’ heat pumps. If a homeowner has an electricity-powered furnace, he recommends replacing it with an air-source heat pump. “Within two to three years, they pay for themselves,” Harkins said.

The process of installing an air-source heat pump system is relatively straightforward, Honeycutt said. He recommends that consumers speak directly with their HVAC installer to understand the system, ensure it meets their needs and choose the most cost-effective option.

Heat pump systems typically include a backup heating option, often referred to as a “heat strip.” These coil-like elements within the system generate heat when electricity flows through them. The heat pump system’s fan blows air across the strip, distributing heat throughout the home. “When the temperature gets below freezing — about the low 20s — that’s when heat pumps stop being efficient and auxiliary backup systems and heat strips kick in,” Gomez said.

A backup heat strip would probably not be needed very often in Central Texas. “They’re only designed to kick in at certain low temperatures,” Gomez said. The strips can also serve as a backup heating source if a heat pump is not functioning, he added. If it does kick in, it’s not cheap: The strip can use up to five times more electricity per hour than the heat pump alone.

In Texas, especially in rural areas where homeowners rely on electricity or propane to heat and cool homes, heat pump systems have become a standard option for new homes in the last few years.

Adam Hernandez is a co-founder of HDZ Builders in Chappell Hill. The custom home and residential construction company serves customers including Bluebonnet members in Austin, Colorado and Washington counties. He is a believer in heat pumps.

“In my opinion, the heat pump is a better system,” he said. “Unlike natural gas or propane heating systems, heat pumps do not produce condensation that can freeze in winter.”

One system that both heats and cools a home is also simpler mechanically. An air-source heat pump should have twice-yearly maintenance checks, much like traditional HVAC systems. That maintenance includes cleaning coils and checking that auxiliary heat systems are working properly, Gomez said.

What do heat pumps look like? “You’d never be able to tell from the outside of a home whether it is a heat pump or a conventional HVAC system,” Honeycutt said. “They look the same.”

Inside the home, however, they look different. A conventional HVAC system has two parts: a furnace for heating and a coil for cooling, typically housed in more square-shaped units. The heat pump’s simpler system is a single, more horizontal and compact unit that takes up slightly less space. Like the HVAC system, it is usually installed in an attic or closet.

Eric Middaugh believes his home's combination of spray foam insulation and heat-pump technology will create an efficient system. By sealing air leaks and eliminating the need for natural gas or propane, the setup should not only save money by reducing electricity use but also offer a more environmentally friendly heating and cooling solution — one that he expects will attract more consumers to heat pumps.

— Alyssa Meinke contributed to this story

Side by side: Heat pumps or traditional cooling/heating systems

Both systems can keep your home comfortable year-round. Which is right for you?

Air-source heat pump system |

HVAC system |

|---|---|

| HOW IT WORKS | HOW IT WORKS |

|

A single unit that works by moving heat in different directions. To cool, it absorbs heat from indoor air using a refrigerant, then transfers it outside. To heat, it pulls warm air from outside, even on cold days. It easily switches between heating and cooling by changing the direction of the refrigerant’s flow. |

Two systems: an air conditioner to cool the home, a furnace to heat it. The air conditioner uses refrigerant to absorb indoor heat and transfer it outdoors. Electric or gas furnaces generate heat to warm air being pushed into the home. |

| EFFICIENCY | EFFICIENCY |

|

Can reduce heating costs by up to 75% because it transfers heat instead of generating it. If temperatures drop significantly below freezing (typically in the 20s), a heat pump typically switches to an auxiliary or backup energy source, such as heat strips, to generate heat – but that uses much more electricity. |

Two systems typically use more electricity and/or natural gas. Electricitypowered furnaces are less efficient than heat pumps, but they maintain warmth better when temperatures drop into the 20s. |

| COST | COST |

|

Typically costs 10%-15% more up front, but will reduce electricity bills over time. Prices for a new system vary widely — from $6,000 to as high as $25,000, including installation, for a 2,500-square-foot house in Central Texas. System costs vary based on county, size and number of units, features, warranties and maintenance packages. Rebates and tax incentives may be available. Installation costs vary based on system size, design/construction of house, pump brand and efficiency rating. If replacing an existing HVAC system, using existing ductwork can save $1,000 to $5,000, unless upgrades or additions are needed. |

Often lower upfront costs, ranging from $3,900 and $10,000 on average for a 2,500-square-foot Central Texas home. Operating costs can be higher due to inefficiency of systems; cooling costs more comparable to heat pumps with similar efficiency ratings, heating costs typically higher due to price/consumption of natural gas or electricity. Rebates or incentives may be available for high-efficiency furnaces or air conditioners. |

| NEW HOME VS. EXISTING HOME | NEW HOME VS. EXISTING HOME |

|

Ideal for new homes with energy-efficient designs. Retrofitting a heat pump system into an existing home may require upgrades or additions to ductwork, adding to the cost. Ductless mini-split systems, which heat smaller areas such as individual rooms, may be a more cost-efficient solution. |

Easier to install in existing homes with ductwork already in place. Adding or repairing ducts can increase costs, especially in older homes. Some homeowners install two systems — a traditional air conditioning unit for summer, a heat pump for winter. Some also opt for a traditional furnace for use when temperatures drop below freezing. |

| LIFESPAN & MAINTENANCE | LIFESPAN & MAINTENANCE |

|

Can last 10 to 15 years with regular, semiannual maintenance by a qualified installer with heat-pump system experience to clean filters, check refrigerant levels and inspect components. |

Furnaces typically last 15 to 20 years; central air conditioners last 10 to 15 years, on average, in Central Texas. HVAC also needs twice yearly maintenance by experienced technicians for air conditioner in warm months and furnace for cold months. |

| AVAILABILITY | AVAILABILITY |

|

Widely available and growing in popularity, but increased demand may lead to installation delays in some areas. Availability will vary by unit size. |

Readily available with a broad range of sizes and efficiency levels. Installation and repair services are widely accessible due to systems’ long-standing market presence. |