Prenatal care can be sporadic for rural women, raising health risks for mom and baby. Out-of-town trips can be necessary for checkups during pregnancy or ultrasounds.

BY MARY ANN ROSER

Brittany Hardy was at home in Paige when she realized her first baby might be arriving in a hurry. She and her husband, L.J., jumped in the car and headed to the hospital — fast.

But fast is a relative term when home is in rural Bastrop County, and no maternity ward is close by. Hardy had been seeing an obstetrician/gynecologist who practices at St. David’s Women’s Center of Texas, where she planned to have her baby. The drive to North Austin takes 45 minutes to an hour from her home.

“It was scary,” Hardy said of the frenzied dash she and L.J. made in March 2016. She got to the Austin hospital in time, but when she was pregnant with her second child, she decided not to tempt fate. She scheduled her son’s delivery and her labor was induced at the hospital four days before his due date.

“I was terrified I was going to end up having him in a car somewhere,” said Hardy, who is a member service representative for Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative.

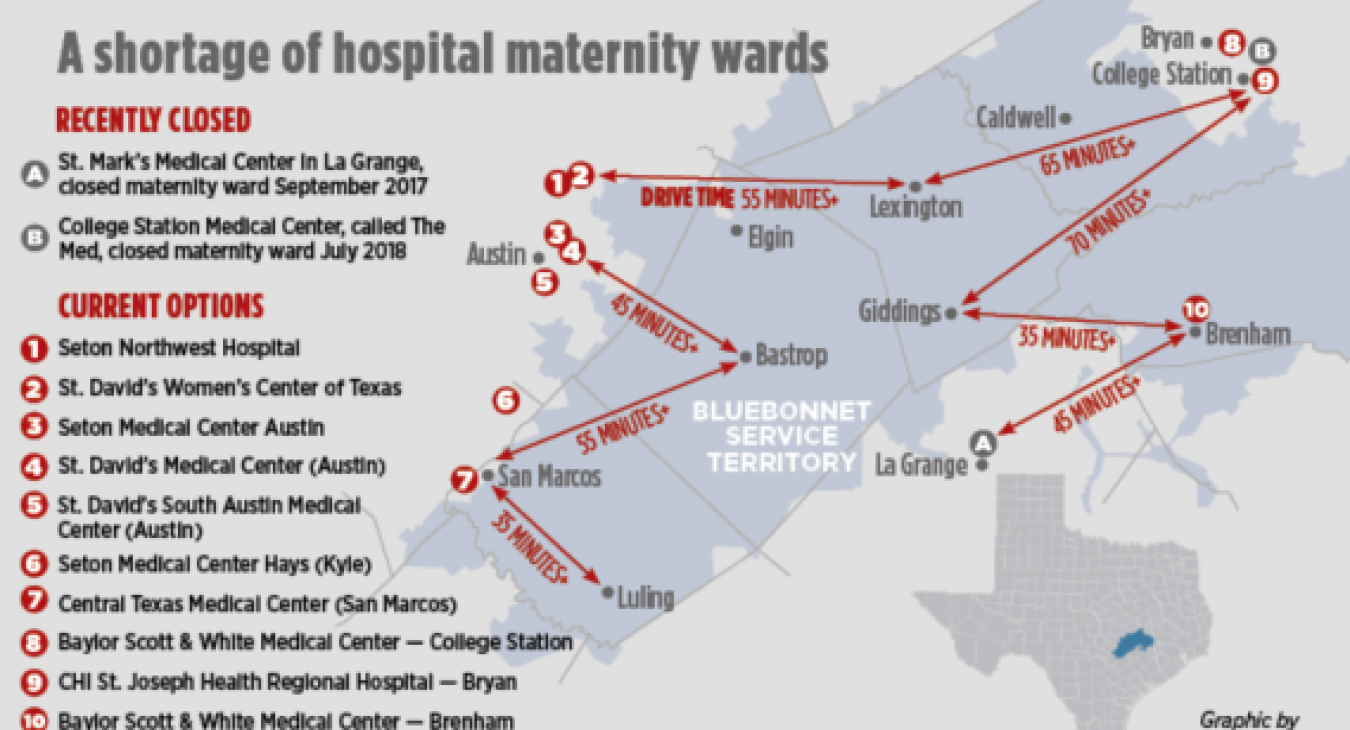

In rural parts of Central Texas, that fear is very real. The nearest hospital maternity ward can be a longer, farther drive than it was just a few years ago.

That’s also true in other communities across America, as more rural hospitals have stopped delivering babies or have shut down altogether.

The percentage of rural counties with hospital-based maternity care fell from 55 percent in 2004 to 46 percent in 2014, according to a March study in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Over that decade, the study found that pregnant women in remote rural areas had a higher risk of complication-related hospitalizations than women in urban areas, and their babies had higher rates of being premature, below weight or dying.

Many women who live in rural Central Texas who want a hospital birth like Hardy must travel an hour or longer when labor starts.

Over the past 13 months, two more Central Texas hospitals that serve rural women have shut their maternity wards: St. Mark’s Medical Center in La Grange on Sept. 30, 2017, and College Station Medical Center, called The Med, in July 2018. Almost always, the reasons for the closure are financial.

“This is an alarming trend,” said Don McBeath, director of government relations at the Texas Organization of Rural & Community Hospitals, known as TORCH.

In the United States, 87 rural hospitals closed between January 2010 and Sept. 21, 2018, according to the North Carolina Rural Health Research Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Of those closures, 15 were in Texas — the most of any state.

In areas that lack a hospital maternity ward, full-time obstetrician/gynecologists are often also scarce. That means prenatal care can be sporadic for some rural women and non-existent for others, raising health risks for mom and baby.

It also means out-of-town trips can be necessary for checkups during pregnancy or for ultrasounds.

Some women in remote parts of West Texas have to fly to Lubbock for prenatal appointments, said Dr. John C. Jennings, a past president of the American Congress of Obstetrians and Gynecologists who works with Texas Tech University’s medical students and residents (doctors in training).

TORCH issued a report in February 2018 that says more than half of the 254 counties in Texas — 147 — have no obstetrician/gynecologist. Lack of access to prenatal care and childbirth care causes concerns about increased premature births and infant death rates, TORCH’s report says.

FINANCIAL OBSTACLES

Medicaid payments, which cover more than half of the births in Texas, haven’t kept pace with rising health-care costs, hitting rural hospitals the hardest. There, Medicaid covers between 60 percent and 70 percent of births, McBeath said. Many of those hospitals struggle to survive, and opt to save money by closing costly maternity departments — especially those that handle fewer than 100 births a year.

Many rural hospitals told TORCH their obstetric units were losing $500,000 a year.

In addition, legislation stalled in the U.S. Congress that would identify areas in the nation with the greatest shortage of obstetricians so doctors could be placed there temporarily in return for having their medical school debts forgiven. Such loan repayment programs help but aren’t enough to meet the needs in rural Texas, McBeath said.

It’s never an easy decision for hospitals to shutter a service they consider a moral obligation to provide, he added, “but if they don’t stop the bleeding, they’ll lose the hospital.”

In the 1960s and 1970s, most of the 300 rural hospitals in Texas delivered babies. By January 2018, just 66 of the 161 remaining rural hospitals in Texas had maternity wards, according to TORCH.

In addition to the College Station hospital, McBeath said three other rural hospitals in Texas closed their maternity wards this year: Medical Arts Hospital in Lamesa, Yoakum Community Hospital and Good Shepherd Medical Center in Marshall.

Even some rural or suburban hospitals that are part of a larger health system have stopped delivering babies or never offered that service.

Construction is underway on the $30 million, two-story Ascension Seton Neighborhood Hospital, at the intersection of Texas 71 and Texas 304 in Bastrop. The facility is scheduled to open in fall 2019, spokeswoman Erin Rogers said. It will fill a medical-care void in the area, with physicians’ offices and women’s imaging on the second floor, and a “micro-hospital” on the first floor, featuring seven inpatient rooms, seven emergency room beds and two minor procedure rooms. But it won’t have a maternity ward.

In addition, none of Seton’s existing rural hospitals delivers babies, including Seton Smithville Regional Hospital and Seton Edgar B. Davis Hospital in Luling, Rogers said. Seton Southwest Hospital in Austin stopped providing maternity care. The teaching hospital that opened last year in downtown Austin, the Dell Seton Medical Center at the University of Texas, also does not deliver babies. Expectant mothers are often referred to Seton Medical Center Austin.

Today, there are fewer family doctors in rural areas who deliver babies. Physicians don’t want to be on call 24/7, and Medicaid payments are inadequate, said Tom Banning, CEO of the Texas Academy of Family Physicians.

“This is a challenge, but it’s been a challenge for 30 years,” Banning said. “If you want to really influence the workforce, you compensate doctors differently.”

GETTING THERE IN TIME

Kaitlin Dannar had her first child at the 60-bed Baylor Scott & White Medical Center – Brenham in 2016. The Dannar family lives in Carmine in Fayette County, about a 20-minute drive to the hospital — "15 if you’re in a hurry,” Dannar quipped. She was a week past her due date when the hospital induced her labor, she said.

It is not unusual for women living in rural areas to schedule their baby’s delivery or rent a room near the hospital as their baby’s due date closes in.

Dannar said she had a good experience at the Brenham hospital, but would consider going to a birthing center next time, if it were near a hospital.

Stephanie Bise lives in Serbin, 7 miles southwest of Giddings, and scheduled the delivery of her first child at Baylor Scott & White Medical Center — College Station, an hour and 20 minutes from her home. The medical staff induced her labor a few days before her Sept. 22 due date. She received great care, she said.

Some women don’t make it to their chosen hospital’s maternity ward and end up in an emergency department somewhere along the route.

One rural hospital between Abilene and Dallas that doesn’t have a maternity ward recently delivered two premature babies in the ER, McBeath said. As a result, neonatal intensive care teams flew in from the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex, picked up the babies and flew back to hospitals in that urban area, he said.

The good news is the babies did well, he said. “The bad news is, those were Medicaid deliveries and cost taxpayers hundreds of thousands of dollars. Could that have been avoided if the hospital had a maternal or neonatal care program? I can’t know for sure, but my answer is yes.”

CALLING ON A MIDWIFE

Midwives are helping to fill maternity care gaps in rural America. Two midwives serving in the Bluebonnet region said that many women who opt for a natural birth with the assistance of a midwife prefer to have their child at home or at a birthing center because they want a calmer environment than a hospital delivery room. Most of their clients seek out a midwife, regardless of hospital proximity.

“There’s a certain type of woman who is attracted to home birth,” said Ulrike Schmidt, a licensed and certified professional midwife who lives in Bastrop and attends home births in Austin, Bastrop and surrounding communities. “The care is so different.”

Schmidt, founder of Heart of Gold Midwifery, once had to transfer a woman in labor at home to a hospital. The woman needed a cesarean section — a surgical delivery performed in a hospital. A woman with a high-risk pregnancy should not plan to have a baby at home, Schmidt said. “We’ll err on the side of caution.”

Licensed and certified professional midwife Toni Kimpel, of Brenham, operates Traditional Midwifery Services and opened Jubilee Birth Center in Bryan more than six years ago because of patient demand, she said.

The women wanted a midwife delivery but didn’t want to have the baby at home or be far from a hospital, Kimpel said. Like other midwives, she provides prenatal checkups throughout pregnancy and attends home births. Kimpel said her business has increased in recent years from 30 births a year to more than 60.

The ranks of nurse-midwives are growing. They managed 12.1 percent of vaginal deliveries in the United States in 2014, up from 10.5 percent a decade earlier, according to the American College of Nurse-Midwives.

The number of certified nurse midwives in Texas has increased from 282 in 2007 to 417 in 2017, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services’ Health Professions Resource Center. A handful of midwives serve women in rural Central Texas in private homes, hospitals and birthing centers, including the new Bastrop Birthing Center, National Birth Centers in San Marcos and Kimpel's Jubilee Birth Center in Bryan.

The idea of educating maternity-care physicians and nurse-midwives side-by-side “so they learn to work together from day one,” is being promoted by the national obstetricians/gynecologists group, but such a training system would face regulatory barriers, said Jennings, the Lubbock doctor.

Jennings isn’t optimistic a solution will be found before the gap in rural maternity care reaches a crisis. Twenty-seven percent of obstetrician-gynecologists are at least 60 years old, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges. Having midwives regularly handle uncomplicated births and refer women with difficult pregnancies to collaborating physicians would help, Jennings said.

Leigh Blankenburg of Lexington had four of her five babies with Kimpel. The other one, her first, was born in a hospital. It was not a pleasant experience, Blankenburg said.

“There’s something so calm and peaceful about birthing your baby at home. I wasn’t confined to a bed … like in the hospital. The protocol that went on just didn’t seem natural. Even if there were a hospital next door, I would not choose it,” she said.

Another of Kimpel’s clients, Nancy Anderson, feels the same way. Anderson lives in West Point, a small community between Smithville and La Grange on Texas 71, and has six children. Her first child was delivered at a hospital. So was her second child, who was breech and had to be delivered by C-section. Anderson’s other four children were born at home, with no complications.

But because of the unpredictability of childbirth, midwives don’t always arrive in time for the birth. Anderson said her husband delivered two of those four babies born at home.

Whitney Faske lives outside of Giddings and also wanted a midwife to attend her baby’s birth, but in a hospital. She chose a physician-midwife group that delivers babies at St. David’s Women’s Center of Texas in North Austin, where she had her three children. The drive takes an hour, Faske said, but she wasn’t worried about the distance.

The important thing for her was finding a group practice that provided natural childbirth. The practice’s birthing center would have been ideal, she said, but her insurance wouldn’t cover the delivery unless it was inside a hospital. Faske said she wanted to be near a full-service medical center in case she or the baby had a problem.

“Looking back on it, I would be totally comfortable with a home birth,” Faske said. Having a baby “is the most natural thing we can do.”