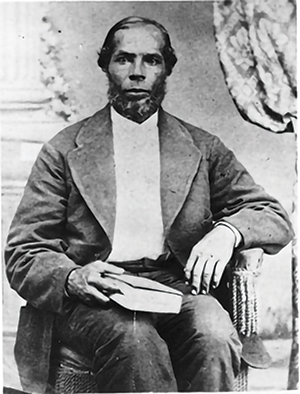

Before Elijah Campbell was a letter carrier for Ledbetter from 1906-1937, he lived in the Lee County settlement of Sweet Home. Such Freedom Colonies proliferated throughout the region.

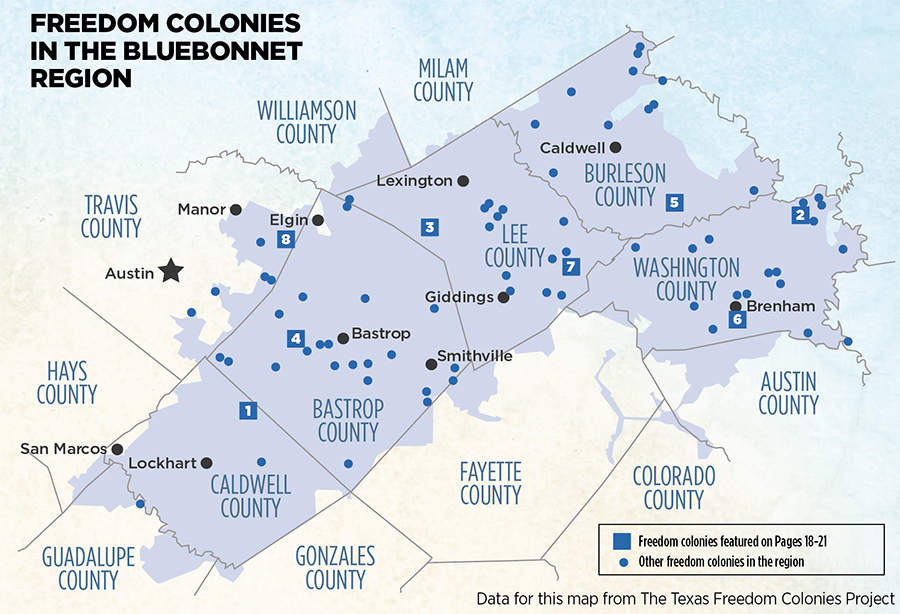

They are called Freedom Colonies: at least 65 settlements, built by newly freed Black people, established across the Bluebonnet region more than a century ago. Family histories and dedicated descendants keep their stories alive.

Story by Clayton Stromberger l Photos by Sarah Beal

Tucked away in the Post Oak Savannah about 10 miles northeast of Lockhart, the unincorporated community of St. John Colony is country-quiet much of the year, just like the rest of rural Caldwell County. Passing through on FM 672, you might note a few church buildings, a small museum and a historic cemetery, and then you’re winding your way toward Dale or Red Rock.

But visit St. John Colony on the third Saturday in June, and you’ll witness a remarkable transformation: Big family groups typically gather under old oak trees as children shout and play. Barbecue smoke wafts across the 10 acres of land between St. John Missionary Baptist Church and the St. John School Museum near the intersection of St. Johns and Carter roads. During the morning’s official Juneteenth program, hundreds of voices come together in a joyous rendition of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” the poem-turned-hymn written in 1900 and often sung in Black communities as a prayer of thanks to God and for freedom.

Juneteenth — honoring June 19, 1865, the day the end of slavery in Texas was officially announced by Union forces that landed in Galveston — has been celebrated on this site for more than 150 years. Although celebrated in Texas officially since 1980, Juneteenth was declared a national holiday in 2021.

St. John’s founders were 14 Black families who made a trek in 1872 from the Elgin area to Caldwell County to carve a new community out of the undeveloped countryside. The families purchased land and built homes, churches, schools and stores.

St. John flourished through the early 20th century, but then gradually declined in population, like many rural communities. In 1910, about 80% of Texans lived in rural areas; by 1970, that number had dropped to 20%. St. John was part of that change. In 1966, St. John schools became part of the Lockhart school district, and by the 1970s, local stores and cafes had closed.

Still, at least 50 current and former area residents come to St. John Regular Baptist Church, at 110 St. Johns Road in Dale, every Sunday to worship. Today, about 300 people live within the original boundaries of St. John Colony, according to retired Caldwell County Commissioner Joe Roland. Of those, about half are believed to be descendants of the original settlers. Many of them continue to keep the history of St. John Colony alive.

Throughout the Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative service area, freed Black men and women formed many independent communities after the Civil War, and countless people can trace their family histories to those settlements.

Most Freedom Colonies were settled near large cotton plantations in the state’s eastern half. At least 65 of the colony sites that have been identified by the Texas Freedom Colonies Project are in the Bluebonnet region.

Stories about Freedom Colonies — and how they survived against all odds, often in the face of extreme hardships and racial prejudice — have long been part of oral histories passed down through generations of Black families. In their 2005 book “Freedom Colonies: Independent Black Texans in the Time of Jim Crow,” authors Thad Sitton and James Conrad brought attention to this often-overlooked part of the state’s history.

Once called freedmen’s towns, 557 Freedom Colonies were founded in Texas by newly freed Black people during the decades after the Civil War, according to the project, created in 2014 by Dr. Andrea Roberts, an associate professor of urban planning at Texas A&M University at the time. Today, Roberts is an associate professor at the University of Virginia. The project’s website, thetexasfreedomcoloniesproject.com, features detailed research and public input to provide information about hundreds of settlements on an online atlas and interactive map.

After emancipation, an estimated 250,000 formerly enslaved Black people lived in Texas. Some were able to save enough money to buy their own land and avoid an oppressive system of sharecropping that led many workers into deep debt to their employers. Other Black citizens sought land in outlying areas that was neglected or considered unsuitable for farming, such as floodplains and bottomlands.

The dream of land ownership became a powerful driving force toward true freedom. In 1870, only 1.8% of the state’s Black farmers owned land. But by the early 20th century that number had reached 31%, the largest share of any state in the country at that time.

That population started to decline in the 1920s, as Black Texans began to leave the state. Over the next 50 years, they joined an exodus of about 6 million Black people who relocated from the American South to states in the North, Midwest and West.

Some Freedom Colony settlements listed on the Texas Freedom Colonies Project map are gone today, but they are still celebrated, in family stories passed down from generation to generation, and through efforts to restore and revive schools and churches. There are settlements in the Bluebonnet area that still survive as small communities.

“These are places where people live today,” said Doris Williams, CEO of the nonprofit Bastrop County African American Cultural Center, where the stories of Freedom Colonies in Bastrop County are being preserved. “They have not disappeared.”

1.

CALDWELL COUNTY

St. John

Descendants of the St. John Freedom Colony in Caldwell County keep the legacy of their ancestors and their community’s history alive. Vessie Tutt, 98, was born in St. John and is the granddaughter of Andrew Davis, one of the colony’s founders. She lives nearby with her husband, Ezelle, a Vietnam War veteran. “This ground is holy,” she said on a recent visit to the St. John School Museum, “because it is ground that people stepped on who were finally free.” The renovated schoolhouse, at 112 St. Johns Road near Dale, features exhibits that tell the story of the colony’s early days. One historic photo in the museum captures a smiling Lue Rece Hill Tennon, wearing her cap and gown on eighth-grade graduation day. Tennon, now 89, returns to St. John as often as she can: “I grew up here, and it’s a part of me.”

When the first residents of St. John Colony arrived, “they held church services under a brush arbor and then built St. John Baptist Church in 1873,” said St. John native Louis Simms, who lives in Austin but is volunteer curator of the school museum. “Our ancestors left a legacy of faith in God.”

St. John Regular Baptist Church, with its ongoing Sunday services, remains the heart of the community, Simms said. St. John had two other churches at one point: Landmark Baptist and Zion Union Baptist, which overlooked the historic St. John cemetery.

— Clayton Stromberger

2.

WASHINGTON COUNTY

Spann’s Settlement

A unique religious history served as the catalyst for Spann’s Settlement, northeast of Brenham and not far from the Washington and Brazos county line. Before the emancipation of slaves in the South, the white family of Malcolm Spann migrated from South Carolina to the area with enslaved people, including many members of the Sweed family, who had converted to Catholicism.

According to the Texas Historical Commission, the Spann and Sweed families worshipped at the same church, a log cabin called the Holy Rosary or Spann’s Chapel. In 1888, Black worshippers established their own church, believed to be one of the first Black Catholic congregations in Texas. That church was destroyed by fire in the early 1900s, but in 1995 a new church was built in nearby Washington.

“In 1969, land deeded to descendants of the Sweed family by the Spann family became the site of a new church building, the Blessed Virgin Mary Chapel, and a hall for the African American Catholic community,” according to the historical commission. “In 1995, the community constructed the newest church building in Washington, which continues to serve the region’s Black Catholics, including descendants of the Sweed family.” The church is at 17370 Sweed Road.

3.

LEE COUNTY

Moab

Early in Texas history, settlers moved onto this land about 10 miles southwest of Lexington in eastern Lee County, and after the Civil War, previously enslaved people moved to the area and established Moab. Like most Freedom Colonies, it was a farming community where Black families could make a living from their own land, growing crops and raising livestock. Some families at that time still depended on picking cotton to earn a living, traveling across Texas and New Mexico to harvest the crop, according to the Texas Historical Commission. Like many Freedom Colonies, Moab peaked in the 1930s, when it had a school, two churches and a post office. Little of the community remains except cemeteries, but for years the Mt. Nebo African Methodist Episcopal Church brought descendants back to Moab to honor their heritage.

4.

BASTROP COUNTY

Cedar Creek and Hopewell

Now a burgeoning, semirural swath between Bastrop and Austin, the Cedar Creek area was home to many Black settlers and more than one Freedom Colony after the Civil War. In 1914, Cedar Creek had 225 residents, four general stores, a gin, a tailor, a doctor, and a cattle dealer, according to the Handbook of Texas. Just to the northeast on State Highway 21, the Hopewell Rosenwald school for Black children opened in 1922. Though it closed in the 1950s, it is among the most intact of 464 Rosenwald schools built in Texas. Construction of those schools — almost 5,000 in rural areas across America between 1917 and 1932 — was funded by Julius Rosenwald, the wealthy part-owner of Sears, Roebuck and Co. In 2015, restoration and renovation of the one-room Hopewell schoolhouse began to gain momentum. That work has continued through community initiatives and donations. The school has been a site for events honoring its past and the area’s history as a Freedom Colony.

5.

BURLESON COUNTY

Birch Creek

The Birch Creek Freedom Colony settlement north of Somerville in southern Burleson County was established around 1890, anchored by the Sweet Home Baptist Church. Though the church has been remodeled several times since, “many original aspects are still there, such as the original log that parishioners sat upon,” according to the website of the Heirloom Project, which researched Freedom Colonies in the county. The church served a network of Black communities in the region. The cemetery at the church also holds the graves of those buried at another Freedom Colony that were relocated with the construction of Lake Somerville.

6.

WASHINGTON COUNTY

Camptown and Watrousville

Two of the earliest Freedom Colonies after emancipation sprang up on the edges of Brenham. At the time, in the 1860s, Washington County was one of the state’s largest cotton producers, and slightly more than 50% of its population was Black, according to U.S. Census data that was cited in a 1994 case study of the area. Camptown was established east of town and Watrousville to the west, and both grew into thriving, politically

active Black communities. Camptown, named for a nearby federal encampment, was the location of the first school building dedicated to “freedman” students in Brenham, according to the Freedom Colonies Project. Wiley Hubert, a prominent Camptown citizen, was key to establishing the school and cemetery there. Watrousville was named after Benjamin Watrous, who was one of five Black delegates to sign the Constitution of Texas in 1869, according to the Handbook of Texas. Several churches and buildings from the settlements remain.

7.

LEE COUNTY

Antioch, Sweet Home

and Post Oak

These three settlements were clustered about 11 miles east of Giddings, where many freed Black people were able to buy inexpensive land in the decades during and after Reconstruction. Antioch quickly became the largest Black community in Lee County, according to the Texas State Historical Association. “Some of the settlers supplemented their income, which presumably came from farming, by working periodically at neighborhood plantations such as Black's Quarter,” the association said. Antioch Baptist Church and its cemetery near FM 141 are still in use today. A book about Texas Freedom Colonies cites an 1890 interview with a couple who said 12 families from Antioch founded nearby Sweet Home. To the southeast on FM 180, the Post Oak settlement was formed in the late 1800s or early 1900s. A school operated there in the 1930s, and there was also a Baptist church and cemetery. The church and cemetery in the Sweet Home settlement area are still in use today.

8.

TRAVIS COUNTY

Littig

The unincorporated community of Littig in far eastern Travis County between Manor and Elgin is believed to be one of the oldest Freedom Colonies in Texas. It took root in the early 1880s on land donated by former slave Jackson Morrow, near where the Wilbarger, Willow and Dry creeks converge about two miles south of today’s busy U.S. 290. Vestiges of the community, which prospered on good Blackland Prairie farmland, still stand on Littig Road, which is also County Road 76. At its peak, the town boasted schools, a post office (run by the state’s first Black postmaster), a general store, two cotton gins and three churches, according to the Texas State Historical Association. Littig’s population dropped from about 150 people in 1936 to 35 by the 1940s. It is still home to a small, mostly Black population. About 315 acres of Morrow’s original land is owned by a conservation trust and is being developed into a farming cooperative.

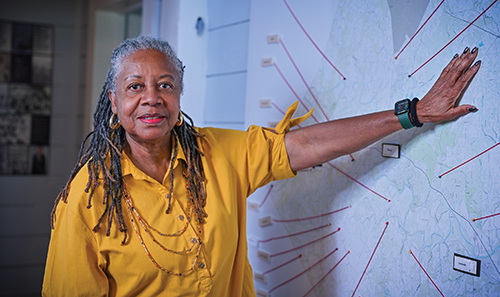

Finding family histories in Bastrop County

Doris Williams didn’t know about her family’s history in the Hills Prairie area of Bastrop County. She was being raised in Lubbock by her grandparents when her grandmother made a request: “Baby, when I die, I want to be buried in Hills Prairie.” Williams’ first thought, she recalls, was “Where is Hills Prairie?”

The small community, about 10 miles south of Bastrop, got its name from Abram Wylie Hill, who bought more than 2,000 acres of area land where he built a mansion in 1857. He had 36 enslaved people working there, according to historical records.

Hills Prairie is listed as a Black settlement on the Freedom Colonies Project website map and database, thetexasfreedomcoloniesproject.com. A small cemetery on Abram Wylie Hill’s nearby property is the resting place for several of the enslaved people who lived there and were given Hill’s last name. After they were freed, some Black residents from Hill’s property moved to the nearby Hills Prairie community and built homes, while others went to live in the Freedom Colony of St. John in Caldwell County.

Motivated to learn more about her family’s history and the city where she was born, Williams and a group of area Freedom Colony descendants founded the Bastrop County African American Cultural Center and Freedom Colonies Museum in 2019. They hope to tell the stories of the post-emancipation settlements that ringed the city of Bastrop and the many others across Bastrop County. The center and museum opened in 2020, and moved into the historic Kerr-Wilson home at 1303 Pine St. in 2022.

The center’s board is working with the City of Bastrop to build a new center and museum. “This is a chapter in Bastrop history,” said Sylvia Carrillo, Bastrop’s city manager. “It’s important for us to acknowledge all aspects of our history.”

“This is a labor of love for me,” Williams said. “It’s a chance for me to give back to the community where I was born.”

The museum is open Saturdays from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. except for the second Saturday of each month. School and church tour groups are welcome. Call 512-535-6949 for more information.

See this sotry as it originally appeared in the Texas Co-op Power magazine here.