An unidentified group poses with a 1924 Ford Model T owned by Urissa Rhone before her marriage. Rhone family papers [di_10766]

By Denise Gamino

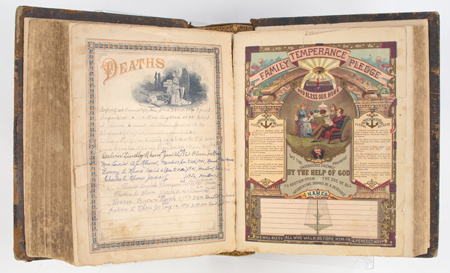

Sometimes, even a chicken coop can be a cradle of history. In 1897, Calvin and Lucia Rhone bought 100 acres in Fayette County. They brought their love letters, financial papers and family photos. They brought their five children and then had four more (another three died at birth). All 12 births were recorded by hand in the big, ornate family Bible.

The Rhones bought 103 more acres in 1917, all within what is now the Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative service area. The family raised turkeys and grew cotton on their 203-acre farm. They also cultivated history.

This respected African-American family, standouts in Round Top as teachers and farmers, preserved scores of personal artifacts that today tell a story of post-Civil War segregation, black perseverance and education, racial integration, family love and the minutiae of everyday life, starting more than a century ago. Treasures include letters from the 1800s, photos of African-Americans and educational records.

The relics were found withering in a chicken coop before being collected by the University of Texas at Austin’s history center, now known as the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History.

The artifacts, called the Rhone family papers, are just the type of household heirlooms that help preserve black history in America. Specifically, they capture some of the character and dynamics of an admired, multigenerational family of middle-class African- Americans in rural Texas.

UT acquired the Rhone family papers in the 1980s, but the surprising story of how they were found and preserved has never been fully chronicled. It involves an airline pilot in Florida who wanted some farmland and his wife, a flight attendant and fifth generation Texan, who wanted to raise their family in the Lone Star State. It involves the Rhone family homestead, found plundered and abandoned outside Round Top. And a dedicated UT archivist who walked into the former Rhone homestead chicken coop, picked up every photo and piece of paper she could find and drove them to her Austin garage in a Volkswagen van.

A UT memo calls the collection “an extraordinarily rich source of information” for studying African-Americans in Texas, “particularly since the collection covers nearly 100 years, with substantial correspondence existing for each decade between 1880 and 1970 (and) numerous excellent photographs.”

“African-American multigenerational collections are not that common,” said Kate Adams, a recently retired UT archivist and curator who retrieved the Rhone collection from Round Top. “There was never any question that we would want this.”

In 1983, Adams was assistant director of UT’s Eugene C. Barker Texas History Center (now part of the Briscoe Center) when she heard about the Rhone keepsakes from a historian at the Texas State Historical Association. A family who bought 50 acres of the deserted Rhone homestead in 1977 wanted to donate the photos and papers.

The donors, Rich and Linda Colby, had found the dilapidated, 800-square-foot Rhone house in disarray when they came from Fort Lauderdale, Florida, to look at real estate in Round Top.

“It looked like somebody had ransacked the whole house looking for valuables and just let it lay,” Linda Colby said. “The furniture was gone, but the papers and things were just there — books, stacks of papers, stacks of magazines like Ebony and things. All kinds of stuff.”

By that time, the last Rhone family member to live in the home had died.

Rich Colby was busy flying for National Airlines out of Miami. Linda Colby, who had been a flight attendant, was a stay-at-home mother and expecting a child. Before the Colbys moved from Florida to the former Rhone farm, Linda Colby’s parents, the late J.F. and Bonnie Knox of Houston, drove on weekends to Round Top to clean the old house.

Bonnie Knox was entranced by the Rhone family’s memorabilia and urged her daughter to save it. “My dad would be cleaning in one room and then he’d go into another room and see my mother reading another letter,” Linda Colby said. “He said, ‘We don’t have all day, Bonnie.’ But thank goodness she had that love of history and preserving things.

“My mother thought there was value to this,” Linda Colby said. “She put it aside. I was not the historian; my mother was.”

Linda Colby’s parents packed the Rhone family papers and photos in boxes and bags. Then, when the Colbys moved in, Rich Colby transferred the collection to the best storage shed on the property: a large, empty, walk-in chicken coop. The collection remained in the coop for several years until the Colbys got to know then-UT professor Jim Ayres, founder of UT Austin’s popular Shakespeare at Winedale program near Round Top. Ayres suggested the Rhone family papers be donated to UT’s history center.

“I just knew it had to do something more than sit in the chicken coop,” Linda Colby said. “I never had the time to go through it.”

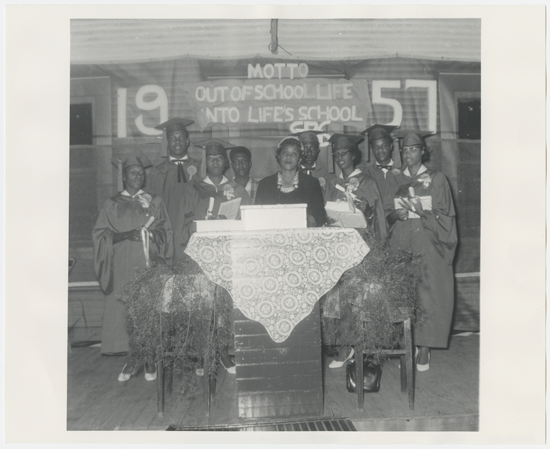

The bulk of the Rhone family papers had been collected and preserved by Urissa Rhone Brown, one of Calvin and Lucia Rhone’s daughters who died in 1973. Brown earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Prairie View A&M and spent a long career as a teacher in segregated schools in various Texas towns from the 1930s through the 1960s. She transitioned to the Round Top-Carmine school district when classrooms were integrated in 1966. She served as principal of the elementary, junior high and high schools.

Urissa Rhone Brown and her husband, Roscoe, lived in the Rhone family homestead after her parents died. “She was just such a well-thought-of teacher in this (Round Top) area,” Linda Colby said.

She also was the family historian. Urissa Rhone Brown safeguarded the old family photos and documents as well as thousands of her own school archives and personal papers. And just like her mother had, she saved love letters from her husband.

“She kept everything,” Linda Colby said. “I knew they had to go to be restored and kept for future generations. It was her life’s investment.”

Urissa Rhone Brown’s historical foresight is significant and a model for others, said Michael Hurd, director of the Texas Institute for the Preservation of History and Culture at Prairie View A&M University. It “speaks to the family’s understanding back then of the importance of preservation — telling their story. So many objects of our personal and family histories are summarily tossed, disregarded. However, there’s an increasing awareness about African-American genealogy and the need to tell our stories. And preservation is the linchpin for that.”

That awareness is often heightened during February, which is designated as Black History Month.

Before the Rhone family papers could be processed and archived, UT had to fumigate them twice to protect the collection from mold after being in the chicken coop.

In addition to the papers and photos, the collection includes cotton sacks cut into fabric for dresses, several

colorful church fans with illustrations of Jesus, a calfskin wallet and a powder puff that still contains traces of powder.

The family also kept an 1857 book about the immorality of slavery: “God Against Slavery: And the Freedom and Duty of the Pulpit to Rebuke It, as a Sin Against God,” by abolitionist clergyman George B. Cheever of New York.

Preserved poll tax receipts show that Rhone family members believed their votes were important. The Rhones also were active members of the Concord Missionary Baptist Church in Round Top, founded by African-Americans in Round Top in 1867 and still active today. Calvin and Lucia Rhone also belonged to several African- American chapters of fraternal societies such as the Order of Knights of Pythias, Sisters of the Mysterious Ten and the Grand Court Order of Calanthe, organized in Houston in 1897 to provide burial insurance for blacks.

And six of the Rhone children attended Prairie View and became teachers, UT records show.

Urissa Rhone Brown owned a 1924 Model T and paid $11.25 on Jan. 24, 1925, for state license fees, according to the old receipt. She earned a bachelor’s degree in 1947 and a master’s degree in 1955, according to Prairie View A&M University records. Her master’s thesis focused on Round Top High School’s graduation and drop out rates. She concluded that guidance services, classes and student extracurricular activities needed to be improved.

One class paper she wrote as a graduate student in 1950 examined racial inequities: “To my way of thinking, there (are) no essential mental differences in races.” She called racial inferiority a scar “usually caused by shock, disappointment and humiliation.” She argued that a person should be advised that “the color of his skin and/or the texture of his hair does not necessitate his being inferior.”

She wrote those words five years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat to a white person in Montgomery, Alabama.

“There are still so many stories and aspects of African-American history that need to be revealed, and the Rhone family papers are excellent examples of that,” said Hurd, the Prairie View historian whose institute was created by the Texas Legislature to collect and preserve African-American history and culture in Texas.

“Regardless of where the artifacts were found, so much of them speaks to the family’s understanding back then of the importance of preservation — telling their story.”

THE THINGS THEY SAVED

The Rhone family papers fill 15 archival boxes. Items include:

- Calvin Rhone’s 1903 Fayette County teacher’s certificate for “the colored schools for children.”

- A 1923 receipt for a $1.75 poll tax that Lucia Rhone had to pay for the privilege of voting, just three years after the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granted American women the right to vote. More annual poll tax receipts are dated through the 1950s before the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that poll taxes were unconstitutional.

- Grocery store receipts showing the family liked vegetables and ham and that someone smoked Camels.

- Motor vehicle fee receipts for their 1924 Ford Model T, license plate 277-525.

- Essays written for classes at what is now Prairie View A&M University, the historically black college 50 miles east of Round Top. One essay about perceived racial superiority states that “there (are) no essential mental differences in races.”

- More than 100 photos, including old tintype studio portraits of unidentified people presumed to be relatives or friends.

THE LOVE STORY OF CALVIN AND LUCIA RHONE

By Denise Gamino

Love can live forever on paper.

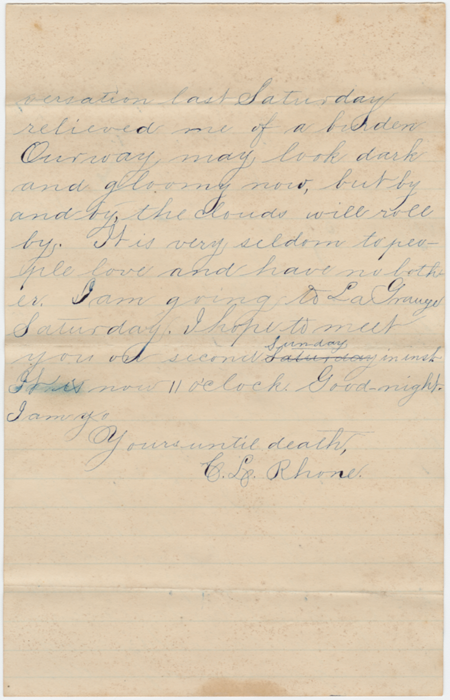

“One thought of your sweet smile cheer(s) me in my lonely hours. I get up and imagine you at my side and your bright eyes smiling in mine, and your sweetest voice of all voices ring continually in my ear,” wrote Calvin Rhone to Lucia Knotts in 1887 before their marriage. “I will be true to you until time shall be no more.”

The tenderness and devotion of the young couple began in the 1880s and lasts to this day, because their 130-year-old letters are preserved at the University of Texas at Austin’s Dolph Briscoe Center for American History. Their love story is valued for its details about middle-class African-American life in rural Texas in the decades after the Civil War.

Calvin Rhone and Lucia Knotts married in Round Top in Fayette County on Dec. 27, 1887, and had 12 children (three died at birth). Their 19-month courtship included 37 letters that outlive them. The handwritten letters make little mention of public events, concentrating instead on their relationship. They debated whether Lucia should continue her education at Prairie View State Normal School (today’s Prairie View A&M University) after marriage. She wanted to. He was opposed.

That courtship tension over gender roles was featured in a 1996 scholarly article in Southwestern Historical Quarterly: “The Courtship Letters of an African American Couple: Race, Gender, Class, and the Cult of True Womanhood.”

“By resisting Lucia’s wish to continue her teacher training after marriage, Calvin reflected the values of the dominant white culture,” states the article written by Vicki Howard when she was a graduate student at UT-Austin earning a Ph.D. She now is a visiting fellow at the University of Essex in England.

“At a time when work and marriage were considered incompatible for women, Lucia’s wish to continue her teacher training, and by implication to teach after marriage, was at least contrary to prevailing white middleclass standards,” the article states.

Lucia won out. Both she and Calvin were highly regarded schoolteachers in Round Top, where Calvin was called Professor Rhone.

Six of their children attended Prairie View, including Urissa Rhone Brown, who earned a master’s degree in education there. Urissa’s long teaching career in segregated schools was capped by her role as a much-admired principal in the integrated Round Top-Carmine school district.

Wisdom was her calling. It was she who kept her parent’s love letters for the ages.

This story originally appeared in Bluebonnet's pages of February's 2017 issue of Texas Co-op Power magazine. Download this story

![An unidentified group poses with a 1924 Ford Model T owned by Urissa Rhone before her marriage. Rhone family papers [di_10766] An unidentified group poses with a 1924 Ford Model T owned by Urissa Rhone before her marriage. Rhone family papers [di_10766]](/sites/default/files/styles/focal_point_inpage_images/public/images/inpage/Group-with-Ford-Model-T.jpg?h=17e6390e&itok=XKa4lj5s)