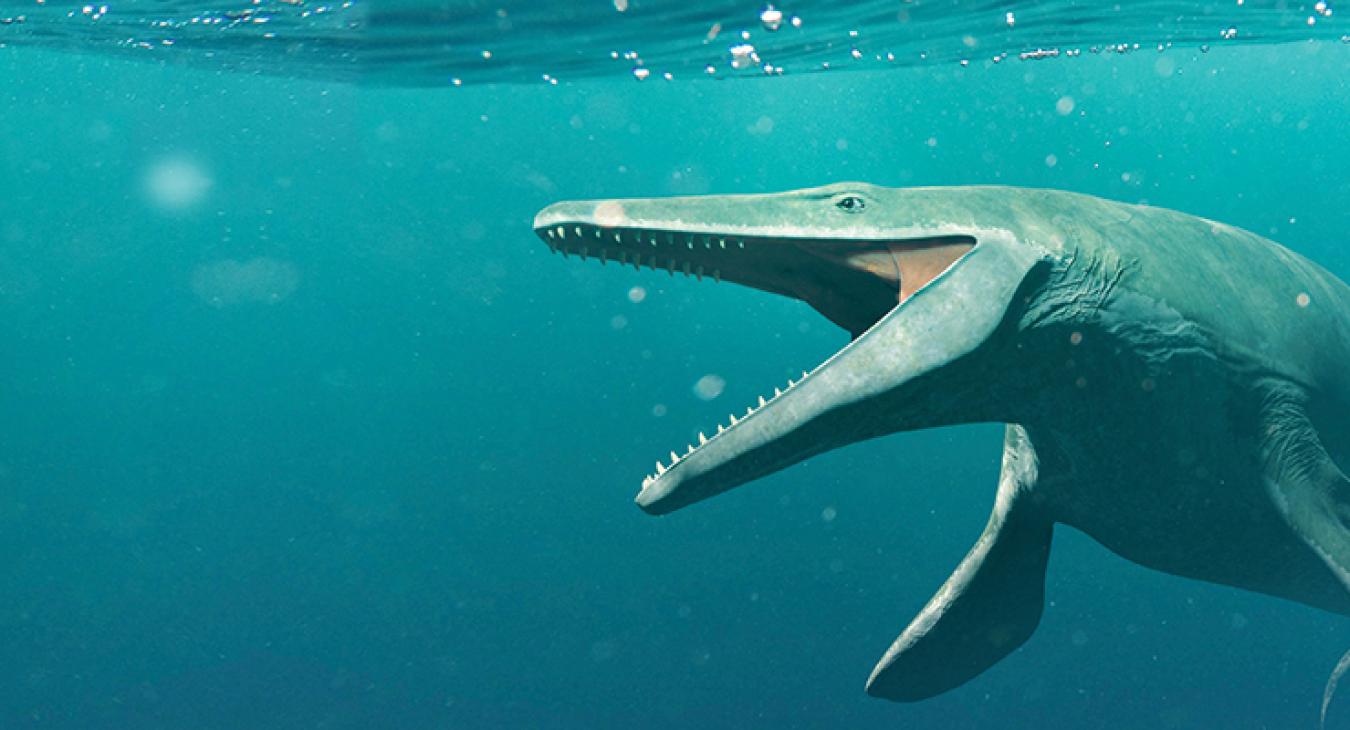

An artist’s depiction of a mosasaur swimming in ancient seas.

This fierce sea creature’s skeleton, spotted a century ago by students, returns to limited public display this year.

By Denise Gamino

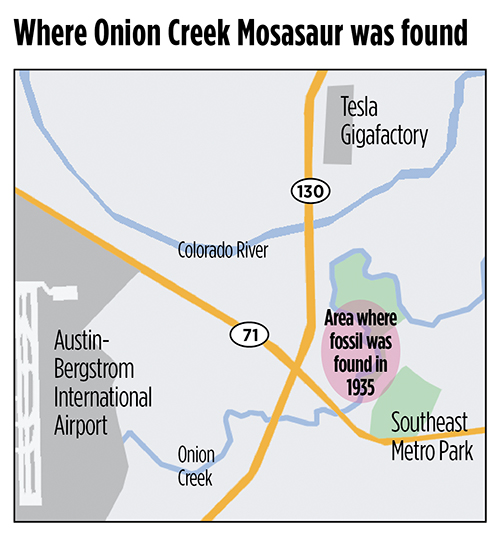

Elon Musk and the Tesla Gigafactory may be the biggest recent sensations in eastern Travis County near the Colorado River, but about 66 million years ago, a truly jaw-dropping phenomenon roamed that area.

SEE THE DINOSAUR PICTURE AND DRAWING SUBMISSIONS

Meet the immense sea creature that got to Texas ages before anyone else.

MORE DINOSAUR SITES IN TEXAS

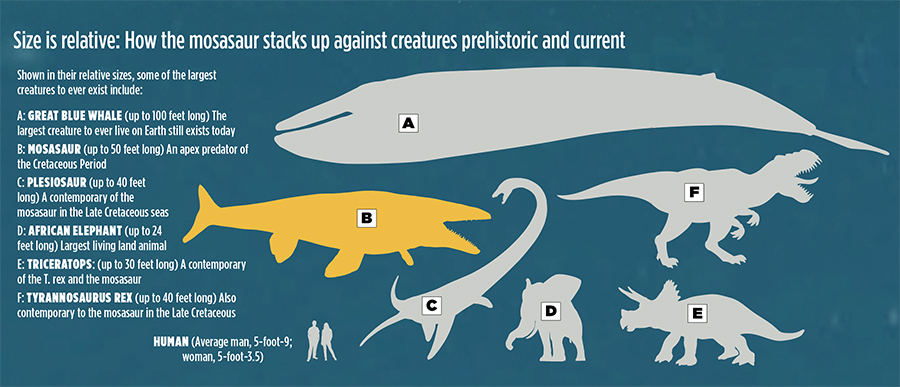

The Onion Creek Mosasaur was a ferociously aggressive 30-foot marine reptile that lived during the dinosaur age. Its 3-foot-wide open mouth and 4-foot-long jaw made it the top predator — and largest animal — in the inland sea that covered much of Texas and 40% of present-day North America millions of years ago. The voracious mosasaurs, swimming in water as deep as 600 feet, “would eat pretty much anything which could fit into their enormous mouths — which, it turns out, was a lot,” according to the National Park Service. Its diet included sharks, fish, birds, ammonites (extinct mollusks) and even other mosasaurs.

The menacing mosasaur (MOSE-uh-sawr) skeleton is the preeminent display at the Texas Memorial Museum on the University of Texas at Austin campus. The museum was closed to the public almost a year ago because of budget cuts, but new funding has allowed behind-the-scenes work to continue. The museum is scheduled to reopen in stages, beginning this fall. The Onion Creek Mosasaur will be seen from afar by visitors at that time, but the public would be allowed a closer inspection of the mosasaur when the second phase of the museum’s reopening occurs in the spring of 2024.

Texas Memorial Museum’s website describes the Onion Creek Mosasaur skeleton as “spectacular.” It’s believed that geologists first saw a part of the giant fossil 100 years ago near present-day Texas 71 and Onion Creek, but the nearly complete skeleton was found there in 1935 by fossil-hunting UT geology students. Those students graduated and went on to have prominent careers in the oil — a fossil fuel — industry.

No one knows whether other petrified mosasaurs may be buried in that area, possibly now covered by roads or buildings. Unlike the federal government, Texas does not require a paleontology review before construction projects begin.

But for at least a century, the area of Onion Creek near today’s Travis County Southeast Metropolitan Park has been known as such a “fossiliferous,” or fossil-rich, spot that it became a favorite specimen-hunting site for UT geology professors and their students. Most finds were oyster shells, clams and other fossilized seashells.

Mosasaurs existed in the Late Cretaceous Period, which geologists believe ended violently about 66 million years ago when an asteroid about 6 miles wide slammed into what is now the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico, causing an enormous inferno and a deadly planetwide dust cloud. The impact is thought to have been as powerful as 10 billion atomic bombs of the type used in World War II. The result was the mass extinction of all dinosaurs (except the forerunners of today’s birds), as well as ocean creatures such as mosasaurs, ammonites and plesiosaurs.

Millennia after that extinction event, on a Saturday afternoon in the fall of 1935, sophomore UT geology students W. Clyde Ikins, from Weatherford west of Fort Worth, and John Peter “Pete” Smith, from Dallas, made the 14-mile trip from the UT campus to the fossil-hunting site on Onion Creek. They were looking for fossilized marine oysters, a common specimen to the area, to fulfill a laboratory assignment.

“We had gone about a quarter of a mile north of the highway bridge on the east bank of the creek when we discovered some bones sticking out of the bank near the water level,” Ikins wrote to UT in the mid-1960s. “We found several vertebrae, rib bones, and a section of the jaw bone about two feet long. The jaw was complete with the large teeth which were used to crush mollusks. The teeth were so well preserved that they had their original polish and luster. At this stage we were very impressed with our find, but had no idea that it would turn out to be probably the most complete mosasaur skeleton that has been found to date.”

Smith was equally proud. “We got a great thrill out of the find as I had been hoping to find one since the day that Dr. (Robert) Cuyler (associate professor of geology) took us on our first Geology 1 field trip,” he wrote in a 1967 letter to UT. “He mentioned that they (mosasaurs) were around, it just took time to find them.”

Ikins and Smith dug out several mosasaur bones that day and brought them back to UT.

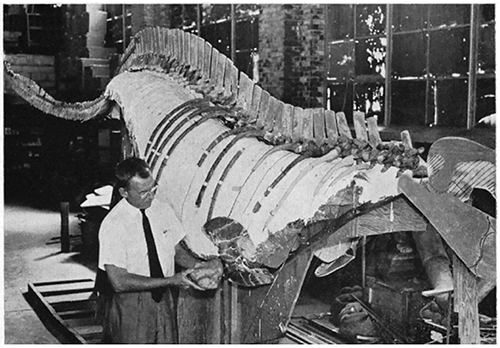

University geology officials were beyond elated by the rare discovery. The prized bones were found just in time to be excavated and showcased in UT’s Gregory Gymnasium as part of a statewide extravaganza to celebrate the 1936 Texas Centennial. They also hoped the mosasaur would bring public and scientific enthusiasm for the Texas Memorial Museum, then in the planning stages. It would open in 1939.

UT’s 1936 Centennial Exposition featured an array of Texas natural science exhibits — such as dinosaur tracks and anthropology dioramas — that drew visitors from all over Texas as well as every other state and 39 countries. The expo ran from June through November 1936, and then cleared out for UT basketball season. It was so popular that visiting hours had to be extended to accommodate the crowds, who could watch the mosasaur bones (except for the skull) being cleaned, preserved and readied for display.

The Onion Creek Mosasaur skeleton “is a particularly lucky find because the specimen is perfect,” noted the late H.B. Stenzel, a geologist who directed the 1936 excavation for UT’s Bureau of Economic Geology, the university’s oldest research unit. His comments were included in a June 7, 1936, UT press release about the Centennial Expo. “With careful supervision, we will have the most perfect specimen of mosasaur yet found in the world.”

Unfortunately, a calamity at the end of the expo delayed the mosasaur’s full public debut at the Texas Memorial Museum for several decades. Workers moving the mosasaur skeleton dropped it, and the bones shattered into many pieces and small fragments. “It remained in this condition for years and years,” Ikins wrote in his mid-1960s letter to the Texas Memorial Museum. “I think the only part of the skeleton that remained in any recognizable form was the head.”

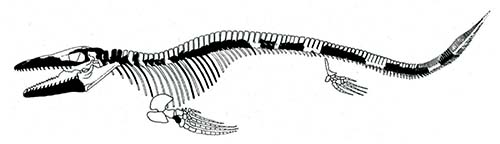

The mosasaur remained asunder until the 1960s, when notable paleontologist Wann Langston, Jr. arrived at UT. He began a two-year process of reassembling the mosasaur skeleton and reconstructing some missing parts so the entire thing could finally be put on public display.

“The paleontologist and preparator reassembled all parts of the skeleton in a natural (swimming) position,” Langston wrote about the mosasaur in a 1966 detailed scholarly study for the Texas Memorial Museum. “As is usual with fossils, some parts of the Onion Creek Mosasaur had been lost before the skeleton was buried and some bones were destroyed by weathering before the discovery was made,” Langston wrote.

“Missing parts were molded in plaster and assembled in their appropriate places among the original bones. These included most of the paddle bones, some vertebrae, ribs, and various parts of the skull and jaws.”

The mosasaur quickly became the museum’s top exhibit when it went on display in the mid-1960s. Ten years later, UT learned that the university’s connection to the mosasaur was older than previously thought.

In 1975, former UT geology student L.T. “Slim” Barrow, the retired board chairman of Humble Oil and Refining Co. (later to become Exxon), sent a letter of congratulations to UT for, among other things, “the perfect job” of reassembling the mosasaur. He said he had been among a group of UT geology students in 1923 or 1924 who had seen some of the mosasaur’s vertebrae at Onion Creek. The students began to dig, Barrow wrote, but “we realized it was too big a job for us and quit before we had done any damage.” Twelve years later, Ikins and Smith found the nearly complete skeleton.

The Onion Creek Mosasaur was far from the only mosasaur that swam the Cretaceous waters that covered much of what is now Texas, while dinosaurs roamed on land. "Fossilized parts of several mosasaur species have been collected from roughly 100 spots in Texas,” said paleontologist and geologist Chris Sagebiel, the current collections manager of UT’s Texas Vertebrate Paleontology Collections. “However, most sites produce only one tooth, or only a bone or two.”

Western Kansas is a hot spot for mosasaur fossils, ranging from single bones to nearly complete skeletons. In Texas, similar “chalk deposits and associated limestone and shale are exposed in a narrow band extending from northeastern Texas (Red River and Bowie counties) southwestward to San Antonio, and westward toward the Big Bend,” Langston wrote in 1966.

“Dallas, Waco, and Austin are all built on these rocks, and mosasaur bones have been found in them, especially in Dallas, McLennan, Williamson, Travis, and Hays counties.”

In 2022, an amateur fossil hunter discovered part of a mosasaur skeleton in the streambed of the North Sulphur River 80 miles northeast of Dallas. Paleontologists from the Perot Museum of Nature and Science in Dallas excavated parts of the fossilized skull, lower jawbone and vertebrae, and plan to continue excavation work.

The exact location of most fossil sites is protected information, and is even exempt from freedom of information laws to preserve them from commercial hunters or vandals, UT’s Sagebiel said. However, the location where the Onion Creek Mosasaur was found is no longer secret because it has been destroyed over the decades by construction on the Texas 71 bridge over Onion Creek. “I believe that the actual (mosasaur fossil) site has since been thoroughly excavated, demolished and concreted over,” he said.

Even with the Onion Creek Mosasaur’s last resting place no longer accessible, Texas still has plenty of ancient creature fossils yet to be found. In fact, the “most fossiliferous site in Texas” is in another part of Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative’s service area, according to the American Federation of Mineralogical Societies. That is a spot along the Brazos River in Burleson County, where a huge deposit of marine fossils includes the remains of snails, oysters, clams and shark teeth.

Collectors have hunted for centuries at that fossil site, under the Texas 21 bridge northeast of Caldwell. Texas A&M University students and science groups still make regular field trips there.

The Brazos Valley Museum of Natural History in Bryan features fossils from the Museum of the A&M College of Texas, which closed in 1965. The Brazos Valley Museum’s collection includes ice age and dinosaur age and casts, including skulls of a mastadon, a triceratops and a Tyrannosaurus rex.

But Texas’ biggest paleontology finds have been made in the Big Bend area of far West Texas. A Texas Pterosaur, with a wingspan of almost 40 feet, was found in that region. You will be able to see its reconstructed skeleton soar in the Great Hall of the Texas Memorial Museum when it reopens in the fall.

***

From fossils to fossil-fuel careers

L. T. ‘SLIM’ BARROW Barrow, who spotted some of the Onion Creek Mosasaur bones in 1923 or 1924, was a native of Manor and played football and basketball for the Longhorns while studying geology. Humble Oil and Refining Company (now Exxon) hired him as a field geologist for surface geologic mapping in Caldwell and Guadalupe counties, where Humble discovered the Salt Flat and Darst Creek oilfields, according to the Texas State Historical Association. He became Humble’s chief geologist in 1929 and rose to chairman of the oil company’s board in 1948. He helped establish a memorial endowment to UT’s Geology Foundation in the late 1950s, in honor of one of his former professors. Barrow died in 1978.

W. CLYDE IKINS One of two UT geology students who found the nearly complete skeleton in 1935, Ikins studied chemistry, botany and geology at UT, earning a doctoral degree in geology. He began his geology career with the Black Mesa Mining Company exploring for brilliant red cinnabar (mercury ore) in Terlingua, near today’s Big Bend National Park. He became chief geologist for Dow Chemical, and later president and CEO of Hondo Petroleum. His botany interests were focused on waterlilies, irises, cacti and succulents. In 1981, he donated his sweeping cacti and succulent collection gathered from around the world to his botanist friend, Dr. Barton Warnock, for a botanical garden in the Big Bend area. Ikins became one of the world’s foremost experts on water lilies and irises. He died in 2005, but today, the peony-like “Nymphaea Clyde Ikins” water lily is still available for sale.

JOHN PETER ‘PETE’ SMITH Smith, along with Ikins, found the nearly complete skeleton in 1935. He went on to become the exploration manager for Esso (Standard) oil’s Libya division and was based in Tripoli. Esso was owned by Standard Oil and became Exxon in 1972. Esso was famous for an ad that encouraged drivers to “put a tiger in your tank” with Esso Extra premium gasoline. Smith retired from Standard Oil in 1967.

History on hold

The Texas Memorial Museum of science and natural history began, appropriately, with a big bang. In June 1936, President Franklin D. Roosevelt set off the dynamite that broke ground for the museum on the University of Texas campus in Austin. Roosevelt, who was on a presidential campaign train trip across Texas, remained on his parked passenger train near present-day East Fourth Street and Interstate 35 while pushing a big red, remote-control button to blast the limestone. The museum temporarily closed to the public in March 2022 because of a staff shortage. However, with university support and fundraising efforts, staff are renovating the museum to open in stages, beginning in September. The Onion Creek Mosasaur will be on display — from a distance — when the museum reopens, but visitors will not be able to get close to it until the second phase of reopening in spring of 2024. The museum is at 2400 Trinity St. in Austin. — Denise Gamino

Meet the Onion Creek Mosasaur!