The cooperative way

Recent news

Story by Addie Broyles

Photos by Laura Skelding

This year, it started with grasshoppers.

The insects came in droves a few months ago, stripping the leaves off peach trees at Ward and Jill Taylor’s farm outside Lexington in Lee County. “They left the peaches dangling off like a Charlie Brown Christmas tree. Then they came and ate the peaches and left the pits. Now they are eating the bark off the trees,” Ward Taylor said.

That was only the beginning. “It’s been brutal,” Ward, 61, said of the damage that this summer of 2022 has brought to the couple’s 40-acre Taylor’s Farm. Twelve years ago, Ward and Jill bought the land because they shared a dream of farming — growing squash and tomatoes during Texas’ typically long growing seasons.

The reality, especially in the last few months, has been closer to a nightmare.

On the heels of a two-decade boom, many small farms in the Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative service area and across the state – often run by farmers with less than a decade of experience – are facing serious troubles.

Weather-related disasters, from a prolonged freeze to this year’s record-breaking heat and drought, have caused severe damage to many small farms. Rising prices, unstable supply chains and labor shortages are adding to farmers’ problems. Many of them are doing what they can to keep going. Those with more experience often diversify their operations to maintain their livelihood. Others relatively new to farming have slowed or shut down operations.

This isn’t the Taylors’ first brush with drought. They’ve been farming here since 2010, starting just before the state’s last historic drought in 2011. Despite the struggles, the couple do not regret leaving their jobs as Boeing employees in Washington state. Ward worked in programming and design there for nine years, and Jill worked in finance for 20 years. They came to the Bluebonnet area to join the wave of new farmers who were setting up shop in Central Texas during the beginning of the locavore, or “eat local” movement of the 2000s.

“Our first year here, our pastures were blowing dust and dirt, and we couldn’t find hay anywhere for the cows,” Ward said. “I remember thinking that if this goes on for any longer, we are going to have to sell our cows off.” But that drought lifted, and the Taylors started what became a thriving farm, raising cattle, pigs and lots of vegetables, enough to feed several hundred families. They sold their produce mostly at Central Texas farmers markets and to area wholesalers.

They, like the majority of small, family farms in the region, use sustainable and organic practices in their farming. Their business peaked after the COVID-19 pandemic started, when the demand for local food was high. Nearly every small farm in Texas had a wait-list for their community supported agriculture program, which lets customers buy a share of a farm’s harvest in advance and receive direct delivery of the food. This allowed the Taylors and other area farmers to sell through new channels. Then the weather started to shift. Again.

“In the 12 years we’ve been here, we’ve had four of the top 12 hottest summers since they’ve been keeping records,” Ward said. The Taylors recently sold their bull to save on feed costs. They stopped going to farmers markets earlier this year and, instead, launched a new farmland leasing program, where beginning farmers could grow their own crops, protected under plastic-covered structures.

This summer’s harsh conditions drove those beginners away, and only a handful of people are interested in the lease opportunity as of early August. “It’s getting bleak for small farmers, that’s what it comes down to,” Ward said. “When the weather’s bad, field prices (the costs of growing) are bad, supplies are short and prices are high. It’s been one thing after the next and all at the same time now.”

The Texas breadbasket

A 2017 report by the Texas Department of Agriculture showed that of the nearly 250,000 farms and ranches in Texas, about 77,500 are operated by producers with fewer than 10 years of experience.

A quarter of new and beginning farmers are under the age of 35, and the number of female farmers has increased almost 70 percent since 2012. That report found the average farm size at the time in Texas was 411 acres, and the average age of farmers/ranchers was 59.

The swath of Central Texas between Austin and Houston is home to hundreds of miles of rich farmland, but the extreme weather of more than a decade could be the new normal for farmers.

“This was the original breadbasket of Texas,” said Brad Stufflebeam, who, along with his wife, Jenny Stufflebeam, started their 12-acre Home Sweet Farm near Brenham 22 years ago. The couple searched the river basins of Central Texas for more than two years before buying their land in 2004.

They dove straight into production vegetable farming, growing crops you’d find in the grocery produce section: leafy greens, carrots, melons and squash. After serving in the U.S. Navy, Brad studied horticulture, started a nursery with Jenny and learned about farming as the head of operations at World Hunger Relief, a farm-based program in Waco.

The organization addresses issues of global food insecurity and malnutrition. At its farm, about 6,000 high school students visit each year. Brad learned that when people first step onto farmland, and see how food is grown, farming can have a powerful allure. Unlike the Taylors, who built up their customer base through farmers markets, the Stufflebeams formed a partnership with about 20 other farmers in the area to build the Home Sweet Farm community-supported agriculture program that served the Houston area for more than a decade.

At one point, the program had nearly 400 subscriber families and a two-year waiting list. But after the 2008 recession and 2011 drought, farmers took a hit. Then grocery stores and delivery services started offering home produce delivery. “After the drought and Hurricane Harvey (in 2017), most of them threw in the towel,” Brad, 51, said. Growing vegetables and producing dairy is what Brad calls “intense farming.” “If it was easy and profitable, everybody would do it. There’s a reason our state is best suited for cattle,” he said.

According to the state’s agriculture department, in 2017 slightly more than half of the state’s agricultural market value was in cattle: $12.3 billion compared to only $352 million in fruits and vegetables. The Stufflebeams got creative about their revenue stream. In 2014 they opened Home Sweet Farm Market & Biergarten in downtown Brenham, the seat of Washington County. They sold that business in 2021 to focus on other new projects. Today the Stufflebeams have a dozen short-term private cabin rentals and give farming workshops, which Brad calls “agritainment.”

They’ve added higher grossing, less labor-intensive perennial plants to their lineup, including tea. They are currently testing varieties. To shield their crops from 2022’s weather, they installed tunnel-like covered structures that protect plants from harsh weather. Earlier, they had dug new 480-foot-deep water wells.

“That saved us,” Brad said, “but even now, we’ve lost a couple of cows this year.” In late July, an older water well on the property went dry for the first time in 50 years. Farming is a long-term investment, he said, which is why a multi-generational farm has an advantage. “The infrastructure is still there. New farmers have to start from scratch.”

Connecting young farmers in Central Texas

Although farmland wasn’t cheap 15 years ago, prices for rural real estate in the Bluebonnet region have shot up in the last few years, said Hayley Wood, an aspiring farmer and director of the Central Texas Young Farmers Coalition, an organization aimed at building collaborative, diverse farming communities.

Wood, 27, is among many who struggle to find arable, affordable farmland these days. Wood grew up in San Antonio but caught the farming bug while working in Latin America.

After returning to Texas, she looked for ways to get experience. She apprenticed at Urban Roots and Community First Village, two community organizations in East Austin that use agriculture as a way to bring people together and teach life skills to young people and individuals who have experienced homelessness.

Wood recently worked at Steelbow Farm, a mixed vegetable farm in Manor on land that, for 25 years, was home to the 15-acre Tecolote Farm. That farm’s founders, David Pitre and Katie Kraemer Pitre, were among the 1990s wave of new farmers in Central Texas who helped create the locavore movement encouraging diners to buy and eat locally produced food.

When the Pitres retired a few years ago, they leased half of their farm to Finegan Ferreboeuf and Jason Gold, who named their business Steelbow Farm.

The Tecolote owners sold the other half of their farm, a separate parcel of land on the Colorado River, to longtime employee Lorig Hawkins. That land is now Middle Ground Farm, but this summer’s drought has brought a pause in activity there for the fall season.

The heat and drought claimed Wood’s farm job, so she started working at Salt & Time, an East Austin butcher shop and restaurant. She also hopes to learn about the business of cattle there while waiting out the harsh weather and economic conditions.

Wood still volunteers 10 to 15 hours a week advocating for young and beginning farmers through the coalition. Every farm is different, she said, but every farmer is just trying to make it to the next season.

Many years ago, it was almost a given that a farmer’s children would take over the farm, but that isn’t the norm today. Nebraska-based Farmers National Company, the country’s largest agricultural landowner services company, predicts that 70 percent of U.S. farmland will transfer ownership in the next 20 years.

“Farming can feel disconnecting in ways that other professions don’t,” Wood said. “It’s essential for farmers to hear from one another. It’s critical that they know they aren’t alone. State resources help, but what is lacking is that peer-to-peer connection.”

The young farmers coalition started in 2013 as a way for new farmers to network through potlucks and educational events. The coalition addresses issues as varied as farm advocacy and mental health. It serves eight counties, including Bastrop, Caldwell, Hays, Travis and Guadalupe, all or parts of which are in the Bluebonnet service area. Although it targets farmers younger than age 45, Wood said, “it’s not about how old you are; it’s about where you want to go and the path that you’re on.”

The Texas Department of Agriculture offers Young Farmer matching grants of $5,000 to $20,000 for people ages 18 to 45. The coalition encourages farmers to look at agriculture through a racially inclusive, community-building lens to make farming careers accessible to everyone. Other organizations such as the National Center for Appropriate Technology and the Bryan-based Texas Small Farmers & Ranchers Community Based Organization reach out to Black, Hispanic, women and military veterans who are beginning farmers and need additional support.

Ryan Farnau is another proponent of farming partnerships.

This year’s drought was hurting his crops, but he had to give up F-Stop Farm, his three-quarter-acre plot in Manor, when the land was sold to developers. Farnau had leased the small corner of a ranch in eastern Travis County for three years, but he started selling produce from his backyard garden in 2013.

His involvement with community-supported agriculture followed in 2014 when he sold his okra, onions, tomatoes and other vegetables at farmers markets and to area chefs.

“The last two seasons have been the hardest growing seasons in memory,” he said. “It’s a bittersweet thing for me to walk away, but I’m committed to being part of the food system.”

Farnau, 50, a father of two children, moved to the Austin area in 2010 from Kentucky by way of California, where he worked as a photographer. He plans to continue making and selling products such as pickles and kimchi, the traditional Korean dish of spicy, fermented vegetables. He is also writing a business plan for a private-public partnership farm with mixed-use development around it.

“Agriculture has always been and will always be a partnership,” he said. “No matter what size of farm, you need other people. If it’s not your father or your brother or your children, you need other people.”

Farnau is working with regional food vendors to prepare foods in their commissary kitchens, which would allow him to sell in area grocery stores and markets. He continues to meet people who want to get into agriculture, particularly millennials disaffected by other careers.

“I don’t want to be Chicken Little about it, but the food system is going to break, and if we don’t build agriculture centers near urban centers, people aren’t going to be able to go to the grocery store and get what they need. We need to remember that we are organisms in an ecosystem, not consumers in a marketplace,” Farnau said.

New ways to keep small farms going

Jill and Ward Taylor aren’t interested in fully retiring or leaving their Lexington property, but their three children aren’t planning to take over the business. In 2021, when they announced plans to lease some land to small-scale farmers, three people expressed interest within a few days.

One of them was Jane Watiri-Taylor, a Kenya-born former nurse who left her job in early 2022 at the Travis County Jail to commit to full-time farming. In March of this year, she was one of several people profiled in a New York Times story about post-pandemic career changes. Watiri-Taylor, who is unrelated to the Taylors, had enrolled in Farmshare, a nonprofit that educates new farmers at a farm in Cedar Creek in Bastrop County. More than 75 students have taken Farmshare’s beginner’s course since 2014, and about a dozen have gone on to start their own farming operations. At Taylor’s Farm, Watiri-Taylor leased one of the tall, protective structures and sold her produce at farmers' markets under the brand Green Thumb Farming. She has since given up her lease, though, and now grows at a community garden near her home in Pflugerville. She sells at an area farmers market.

“She has a realistic view of what it takes to do this,” Ward Taylor said. “But that’s farming for you.”

Connecting with other farmers has been an invaluable asset to Taylor’s Farm in the past decade. “All the cards are stacked against small farmers,” Ward Taylor said. “If people can see the synergy of working together, like buying seed potatoes in bulk or helping out with transportation of feed, we can grow that coordination.”

The pandemic underscored the importance of cooperation.

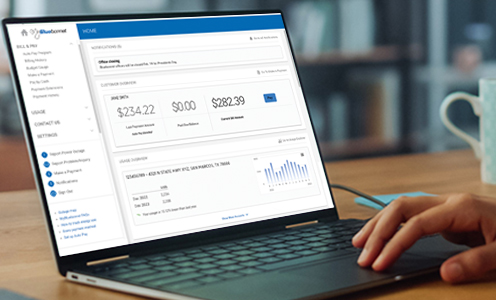

Although many farmers markets continued operating under strict COVID protocols, other farmers, including the Taylors, shifted to selling through websites like Farmhouse Delivery, MilkRun and a service called Barn2Door, which allowed them to host e-commerce on their own website, taylorstxfarm.com.

This year the Taylors have faced new challenges, from grasshoppers to drought to supply price hikes.

There are other downsides to growing vegetables besides the weather. It can be big business, but a lot of people start and then shut down after a few years. New farmers often “don’t realize how much work it is until they get into it,” Brad Stufflebeam said. “It’s either that, or they find a way to make it sustainable,” he added, by using wholesale accounts, farmers markets or direct-to-consumer deliveries.

“Vegetables can bring in $28,000 per acre,” he said, although labor and fertilizer costs eat into that profit. Picking 800 pounds of tomatoes one day and getting them to market the next is an exhausting amount of work. With this summer’s extreme heat, drought and added competition from grocery stores and delivery services, it’s even harder for area farmers to compete. “In Austin or Houston, you can sell a $5 tomato,” Stufflebeam said, but a buyer in Brenham might balk at that price.

Contrast that with the much lower cost of raising cattle – several hundred dollars per acre, on average – and growing produce can start to look like too much work for the investment. “I’d look out at these 12 acres every year, and it looked gorgeous, but every three months I had to dig it in and plant it again,” Stufflebeam said. Wood, of the young farmers group, says that the numbers of new farmers ebb and flow every decade, as new people enter the industry and others exit or change their business model.

“There’s been a big surge of people saying farming is cool, but it’s a complex issue,” Wood said. “There’s a lot of assumption about how easy it is, or that it’s just about growing food and being outside. But the truth is that people want work that is tangible and is meaningful and is shaped around interconnectivity. “I don’t ever discourage people from getting into this field, but I encourage them to think about what they want to get out of farming and to be open-minded about what they might get out of it.”

***

Helpful farming resources

For secure browsing, type https:// before each of these website URLs.

farmers.gov/protection-recovery

farmers.gov/protection-recovery/drought

farmers.gov/loans and its Farm Loan Discovery Tool linked from that page

lulingfoundation.org agriculture demonstration farm offers in-person education, varied crop operations, demonstrations

droughtmonitor.unl.edu to track drought information on the U.S. Drought Monitor

fsa.usda.gov/state-offices/Texas for statewide information and resources

tsfrcbo.org/resources from the Texas Small Farmers & Ranchers Community Based Organization

texashelp.tamu.edu to browse the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service’s Disaster Education Network

agrilifeextension.tamu.edu/browse/program-areas for a variety of departments, programs and units available to farmers and ranchers through the A&M AgriLife Extension Service

***

AN INCREASE AT AUCTION

An increasing number of cattle are being brought to auction across the state, including these, above, at the Lexington Livestock Commission auction July 23, said co-owner Steven Heller. His family has owned the commission since 1956 and he has worked there since he was a kid. About 1,500 to 1,900 cattle are being brought to auction every week this summer, Heller said, compared to the typical 800 to 1,000. ‘‘People are selling because it’s so dry,’’ he said.

Feeding cattle has become more difficult and expensive as the drought wears on. Both experienced and newer farmers are being forced to sell more cattle than is typical. ‘‘The heat and dry weather, it’s one of the worst in the last 50, 60 years,’’ said Victor Yurk, who was selling calves at the auction in July. ‘‘We normally don’t sell calves under 600 pounds, but we’re selling calves that are 450 (lbs.).’’

The level of ‘‘cow herd liquidation’’ in Texas and across the nation this summer hasn’t been seen since the 2011 drought, according to David Anderson, Texas A&M University professor and extension service economist for livestock and food marketing, in a July interview with the Texas Farm Bureau. The cost of raising calves has also increased, he said, predicting a 4% decrease in America’s cattle herds in the next year.

***

INSIDE LOOK

Andalucian Ranch Texas

Where: Bellville, in Austin County

Started: 2018

Size: 200 acres

Owners: Youssef and Giovana Bargach

From: Born in Morocco

What they grow: Grapevines (for wine) and cattle

What they tried to grow: Olive trees. Youssef and Giovana had just finished planting 5,000 olive trees the summer before the 2021 statewide freeze. Every tree died. “I’m stubborn as an ox when it comes to these things, so I purchased 100 (grape)vines for this year and planted them,” Youssef said. “If they take off, then it’ll be a much slower project. It’s a turbulent story. I grew up on a farm in Morocco that was self-sustaining, but once you come over here, things have to be profitable. They can’t just be self-sustaining.”

Advice for the new farmer: “The best thing that I could tell anybody is to start small and build up at a reasonable pace,” Youssef said. “I underestimated how quickly I could burn out.” A new farmer can start with less than 25 acres, he said.

***

INSIDE LOOK

Small Town Farm

Where: Fentress, in Caldwell County

Started: 2019

Size: 1 acre

Owners: Miguel Guerra and Cristen Andrews

From where: Originally from Eagle Pass and Pflugerville, respectively, the former Austinites started looking for land in Fentress along the San Marcos River more than a decade ago.

What they grow: Herbs, native plants, vegetable transplants, which they sell at the San Marcos Farmers Market, along with value-added products like chai-spiced honey and lemongrass tea.

What they tried to grow: Vegetables for the farmers market, which they tried for a year. ‘‘There was no way we could keep doing that,’’ Andrews said.

***

INSIDE LOOK

Whitehurst Heritage Farm

Where: Brenham, in Washington County

Started: 2017

Size: 57 acres

Owners: Michael and Leslie Marchand

From: Started in Cypress, northwest of Houston, in 2014

What they grow: Vegetables for community-supported farm-share boxes, eggs, poultry, pork and cold-pressed juice

What they tried to grow: Meat chickens and turkeys; the Marchands are cutting back the number of animals to a manageable level.

Advice for the new farmer: “Go on YouTube and start watching videos,” Michael Marchand said. “There is so much that is there for the beginning farmer. But if you’re someone who wants to raise a family and do it as your primary business, you need to buy some professional farmers (education) courses for about $2,000 each. Those can take you from knowing nothing to a decent level of skill in a few months. You can also pay a professional farmer to coach you.”

Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative Board member Bryan Bracewell, center, earned his Credentialed Cooperative Director Certificate from the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, which represents more than 900 of the nation’s electric cooperatives.

Bracewell has served as a Bluebonnet director from District 3, Bastrop County, since 2018. To earn this certification, Bracewell completed dozens of hours of classes on topics ranging from board governance to cooperative finances.

It was like asking a parent: Which is your favorite child?

Museums and historical archives across the Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative area are filled with thousands of fascinating items that have taken decades to select and acquire. It takes dedication and a love of history to tell the story of a community through a collection of artifacts.

But surely the folks in charge have a thing or two that holds a special place in their hearts. It could be something simple. Maybe it makes them remember a loved one or it symbolizes a key piece of their community’s past and people. Perhaps it just makes visitors chuckle.

We asked five Bluebonnet-area museum officials to pick out the one thing they could call their favorite. Each of their stories tells you something about them, their work and the vast array of preserved treasures tucked away in our communities.

1944 dress white Navy uniform

Chosen by Kelita Thomas

Lee County Museum

By Dana Frank

Lee County loves its military veterans. You can see it at Veterans Honor Park, just north of U.S. 290 and east of downtown Giddings, where flags, paver stones and an honor wall pay tribute to those from the county who are serving, or served, in the U.S. military.

The county also cherishes its history. All of that brings us to the Military Room at the Lee County Museum, where uniforms from all military branches, most worn during World War II, are on display. All were donated by Lee County residents.

Kelita Thomas likes to linger here. She has an affinity for the 1944 Navy dress white uniform bearing a lieutenant’s insignia and several medals that were worn by M.F. Kieke of Lee County. Thomas, the museum’s curator and president of Lee County’s historical commission, says she grew up “an Army brat” who is “very proud to be from a military family.” She always looked up to her older brother, Michael, who served in the Navy in a ship’s engine room.

“He has always been my hero,” Thomas said. “This uniform makes me think of my brother and all the other brave sailors who do so much to serve our country and keep us safe.” The man who wore the uniform on display was born in 1911.

Kieke was aboard the USS Missouri on Sept. 2, 1945, when representatives of Japan signed surrender documents to the Allied Powers to end World War II. Kieke interrupted his career as an attorney in Lee County to serve his country from 1944 to 1946. His uniform bears an Asiatic Pacific Campaign Medal, a World War II Victory Medal and an honorable discharge emblem.

Thomas, who is also tourism director for the Giddings Chamber of Commerce, was instrumental in creating the Military Room in July 2021 to correspond with the Giddings Sesquicentennial and the opening of Veterans Honor Park and memorial.

Other uniforms in the museum’s Military Room include a U.S. Cadet Nursing Corps uniform and an Army uniform from World War I. The oldest item in the room is a sword from the Civil War, and the “prize of the collection,” Thomas said, is a World War I German water-cooled machine gun.

The Lee County Museum is housed, along with the Giddings Chamber of Commerce and Visitor’s Center, in the two-story Greek Revival–style Schubert-Fletcher home, which August Schubert built in 1879 for his wife and 10 children.

The Baylis Fletcher family bought the house in 1900, and donated it to the Lee County Heritage Society in the mid-1980s. The society donated the home to the county in 2017. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In addition to the Military Room, the front room of the museum displays the home’s original formal furnishings and décor, including the Schubert-Biar family piano and a framed painted Fletcher family tree that dates the family’s roots more than 900 years to 1066. A bedroom and kitchen are also part of this exhibit.

Completing the museum, which Johnson estimates contains 5,000 pieces, are a rotating exhibit and the Lee County History Room.

Kieke was raised in Lee County and went from practicing law to become Lee County Attorney in 1950 and county judge in 1953. He died in 1980 at age 69.

It is fitting that Giddings’ former city slogan, “Home of Opportunity,” was coined by his daughter, then-schoolgirl Twila Kieke. (Today’s city slogan is “Experience Hometown Hospitality.”)

Twila came up with the slogan in a 1950 competition and pocketed $10 for her idea. Perhaps her father’s life of military honor, hard work and success served as inspiration for her winning idea.

Lee County Museum

- 183 E. Hempstead St.,

- Giddings

- 979-542-3455

- Open 10 a.m.-5 p.m., Monday-Friday

- Free admission; donations accepted

Early 1900s custom-made saddle

Chosen by Mike Vance

Brenham Heritage Museum

By Dana Frank

A custom-made saddle allowed a young Dr. W.F. Hasskarl to make house calls after his 1910 arrival in Brenham.

He quickly discovered he was not the only doctor in town, and most rural doctors of that era used carriages or horseback to get to the homes of patients. Cars were a rarity on the region’s dirt roads, though Hasskarl did get a Model T soon after his arrival in town.

To smooth horseback house calls, Hasskarl went to venerable Schramm Saddlery on Main Street in downtown Brenham. The business operated from the late 1800s through World War II. The craftsmen there created a sturdy dark-leather riding saddle that could accommodate medical supplies and equipment.

The well-used saddle, still in beautiful shape after a century, is part of the collection at the Brenham Heritage Museum in Washington County.

“It’s clear that the family took care of it,” said Mike Vance, executive director of the museum. “And we’ve made sure to protect it since it was donated by the doctor’s family a few decades ago.”

The saddle is a favorite of Vance’s because, he said, “It comes with a story that touches on a longtime business and an important family in town.” Vance is also a historian, an author and a documentary filmmaker.

The doctor’s son, Dr. W.F. (Boy) Hasskarl Jr., recounts in his memoir, “Remembering Brenham,” the story of his father and the saddle.

The saddle has a deep and comfortable cantle, which is the back of the saddle seat, to support the doctor’s hips and lower back. Behind the cantle, a wide, sturdy skirt secured saddlebags filled with medical supplies and necessities. The saddle’s stirrups are large, heavy and covered in thick leather. They offered stability and protection on Hasskarl’s rides through brush and branches, as well as some insulation on chilly middle-of-the-night rides.

The elder Hasskarl, a graduate of the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, was one of Brenham’s and Washington County’s most beloved doctors for decades. He was eventually joined by his son, who was born in Brenham and also graduated from the Galveston medical school. W.F. Hasskarl Jr., affectionately known as “Dr. Boy,” joined his father and a family friend, Dr. Thomas Giddings, at a medical practice that became the Brenham Clinic. The elder Hasskarl died in 1955 at age 70.

Dr. Boy, who served as an Air Force surgeon in the Korean War, worked as a physician in Brenham for 50 years, served two terms as the city’s mayor and was the Washington County health officer for 20 years. He died in 2008 at age 91.

The saddle will sit in the Brenham Heritage Museum space when renovations there are complete. The museum’s home is a 1916 former federal building and post office downtown that is expected to reopen to the public in September.

“Our goal is to create the best regional history museum in Texas,” Vance said. During renovation.

Brenham Heritage Museum

- Exhibits temporarily on display at Bus Depot Gallery, 313 E. Alamo St., Brenham

- Permanent facility, Post Office/Federal Building, 105 S. Market St., closed for renovations (completion expected in September 2022)

- 979-830-8445

- brenhamheritagemuseum.org

- Open 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Saturdays; Monday-Friday by appointment only

- Admission free for members, $5 for nonmembers; donations welcome

Early 20th century bogus medical device, the Nerv-O-Meter

Chosen by Rox Ann Johnson

Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives

By Dana Frank

Feeling nervous and jittery? Worried about ... all of it? Considering a curative route but first need a diagnosis? Have we got the gadget for you.

Come see the Nerv-O-Meter at the Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives in La Grange. It is a favorite item of Rox Ann Johnson, an archivist and curator at the museum. The device is a splendid example of the many quack medical devices that became popular in the early 1900s.

The Nerv-O-Meter purports to gauge your “nervisity” (no, that’s not a word) in milliamperes with the help of its accompanying diagnostic instrument, the “micro-quantumeter” (also not a word). The device has an additional tool that, though important-looking in its briefcase-like container, has unstated powers.

During the early 1900s, the medical industry was essentially unregulated and devices like the Nerv-O-Meter were all the rage. Many purported to cure almost any malady, from arthritis to baldness to “neurasthenia,” a not-quite-real condition with symptoms of exhaustion, headache, irritability and general neuroses.

The bogus medical devices, often used by quack medical practitioners, varied in appearance and function and went by colorful names, including The Rejuvenator, violet ray wand, magneto and the Elec-Treat Mechanical Heart, according to reports and advertisements from the time. The devices often delivered low-level electric currents from custom batteries, because, in the early 1900s, electricity, magnetism and even radioactivity were touted as having curative properties.

The Nerv-O-Meter was used by a chiropractor whose office was above the Mohrhusen-Schmidt company, a furniture store at the corner of Main and Colorado streets in La Grange in Fayette County. “The store owner who found these instruments above his business many years ago cut the wires so that his children didn’t hurt themselves,” Johnson said. “Evidently, they liked to play doctor with them.”

The Nerv-O-Meter and its briefcase tool are labeled with the name Fred Besuzzi of Los Angeles. According to a 1955 false advertising lawsuit, Besuzzi was a businessman who loaned money or credit to licensed chiropractors “to enable them to open or buy offices and equipment under the association name of Basic Diagnostic Office.”

The device’s components were added to the museum’s collection more as an oddity than anything historical, Johnson said. “I could only speculate as to how old they are. My take is that they are pure quackery, but what do I know?”

Johnson and her colleague, Maria Rocha, design and create the museum’s exhibits and events. Not all holdings are on display, so if you visit when the Nerv-O-Meter is on hiatus, just ask to see it.

Don’t let the Nerv-O-Meter mislead you, though. The Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives is a research space, with worktables and more than 16,000 historical images in its research collection. It also holds over 17,000 files, documents, scrapbooks, maps and other written materials.

Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives

- 855 S. Jefferson St. (above the library), La Grange

- 979-968-3765 (ask for museum and archives)

- cityoflg.com/library (click on Museum & Archives)

- Open 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Friday; 10 a.m.-1 p.m. Saturday

- Free admission; donations accepted

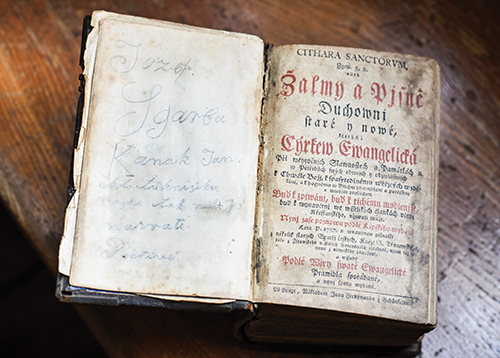

1800s Czech hymnal, smuggled in a loaf of bread

Chosen by Christine Campbell

Burleson County Czech Heritage Museum

By Denise Gamino

The thick brown book had no ticket to ride.

Instead, the vintage Czech holy book that is a Burleson County treasure is believed to have been smuggled out of Europe from what is now the Czech Republic in the 1800s. It was a time its people lived in servitude and their culture was suppressed under the strict Austrian-Hungarian Empire.

The stowaway full of songs and psalms apparently traveled inside an unconventional hiding place: a loaf of bread, according to its provenance document at the Burleson County Czech Heritage Museum and the family who donated it.

If the Protestant holy book had been found by the Empire, it would have been burned. An escape route of more than 5,000 miles brought the hymnbook to its display spot in Caldwell.

Museum president Christine Campbell says the Czech hymnal once considered contraband proves how important religion and culture were to the Czechs who left Europe for Texas.

“My favorite thing at the museum is our Czech hymnal,” she said. “The safety that our Czech ancestors risked to bring these important pieces with them sends a clear message of how important their faith was. We all have a lineage of something. To have a lineage of faith is a beautiful thing.”

Czechs began moving to Texas in the mid-19th century, mostly from Bohemia and Moravia. A 1906 Czech guidebook to a London exhibit about Bohemia states, “Three books are of striking importance and significance in the spiritual and moral development of the Bohemians: The Bible, The Postilla (Bible commentaries), and the Hymnbook.”

The chunky hymnal — 4 inches thick, 7 inches tall and 4.5 inches wide — is titled “Psalms and Hymns, Meditations.”

The publishing date is not known, but it’s signed by three men, including Jan Kanak. He wrote a note in the book: “Whoever finds this book should virtuously return it.”

John Orsag, an engineer retired from NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, is a descendent of Kanak. He grew up in the Czech community of Hrozanka in Burleson County, east of Caldwell, where his parents spoke Czech. His mother, Ella (Zalmanek) Orsag, had a cousin who was a great-great-great grandson of Kanak. He gave Ella Orsag the smuggled Czech holy book because he had no children. About 10 years ago, John Orsag and his two sisters (Emily Orsag Hejl and Joyce Orsag Floeck) donated the book to the Czech Heritage Museum.

“We just decided that would be the best thing to do with it,” John Orsag said. “It was always passed down with the story about how the Bibles were oftentimes baked in bread just to hide them in a place where the authorities were not expected to find them so they could bring them over (to America) and keep them from being destroyed.”

Thadious Polasek, a Czech language instructor at Blinn College in Schulenburg and director of Schulenburg’s Public Library, translated portions of the Czech holy book.

“If, under Austrian-Hungarian rule, the books were found, the owner would (have been) punished,” Polasek said. “Any book in Czech would have had to be hidden in the Czech lands. The people had to be creative — be it in a loaf of bread, be it in a secret compartment in the floor or the well or some secret area of the house — so they would not be discovered when Austrians were coming into the town or walking through houses inspecting for books.

“The goal of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire was to wipe out the Czech culture, to Germanize the people,” he said.

“If you were going to be leaving your home (to emigrate), what are you going to take with you? You’re going to take your Bible, your medical books,” Polasek said. “If they had to get it through customs as they were traveling through the Austrian territory or checkpoint, they had to come up with ingenious ways of hiding it.”

The Czechs’ success in smuggling out their sacred religious books shows “a very deep love of their faith, their culture, their heritage,” Polasek said. “They knew the way to preserve it was to keep the books with them.”

Burleson County Czech Heritage Museum

- 200 E. Fawn St., Caldwell

- 979-567-0000 (Chamber of Commerce)

- Call for open hours or to schedule a visit

- Free admission; donations accepted

1930s bench made in Bastrop State Park

Chosen by Nicole Deguzman

Bastrop Museum and Visitor Center

By Dana Frank

Natural spaces — how they feel, look, sound and smell — are a big draw for Nicole DeGuzman. That’s why she relocated a year ago from West Texas to Bastrop, to become director of the Bastrop Museum and Visitor Center.

“Bastrop and Buescher state parks are some of the reasons I moved here,” she said.

Her favorite museum item represents that natural realm because it was hewn and crafted from walnut at Bastrop State Park in the 1930s by members of the federal Civilian Conservation Corps, or CCC. “The rustic style of this bench was meant to match and blend with the landscape of the park,” DeGuzman said, “just like the buildings and cabins, many of which are still standing.”

The simple wood bench was made before U.S. national park furniture design became standardized. “It is rare that the piece has survived intact,” DeGuzman said. The bench was loaned to the Bastrop County Historical Society in 1996 by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

The hardworking bench isn’t glossy or flashy, and it is sturdy to this day. Museum visitors sometimes sit on it to gaze at exhibits, unaware they are sitting on a piece of Bastrop County history created by a Great Depression jobs program.

DeGuzman’s beloved bench has cedar cousins in the museum: a dining table and three chairs, all in the rustic style that harmonizes with the Lost Pines environment. The furniture at the museum was used in the park’s Refectory, or dining hall.

“A good portion of the original 1930s CCC-made furniture is still at the park,” according to Sally Baulch, the chief curator of the State Parks Cultural Resources Program at Texas Parks and Wildlife.

In the 1930s, President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal offered jobs to young unmarried men between ages 18 and 25 as part of the CCC to build out Bastrop State Park — as well as more than 800 other state and national parks.

Between 1934 and 1937, the Bastrop State Park furniture shop and mill turned out an estimated $75,000 worth of furniture for cabins and other buildings for parks nationwide. In today’s dollars, that is about $1.5 million.

That historic woodshop is still in use today. The brown signs familiar to visitors at any of Texas’ 89 state parks, historic sites and natural areas are made there. Bastrop State Park’s legendary handiwork now leaves a mark all around Texas.

Bastrop Museum and Visitor Center

- 904 Main St., Bastrop

- 512-303-0057

- bastropcountyhistoricalsociety.com

- Open 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Monday-Saturday

- Admission $5; free for 12 and younger and veterans