The cooperative way

Recent news

It was like asking a parent: Which is your favorite child?

Museums and historical archives across the Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative area are filled with thousands of fascinating items that have taken decades to select and acquire. It takes dedication and a love of history to tell the story of a community through a collection of artifacts.

But surely the folks in charge have a thing or two that holds a special place in their hearts. It could be something simple. Maybe it makes them remember a loved one or it symbolizes a key piece of their community’s past and people. Perhaps it just makes visitors chuckle.

We asked five Bluebonnet-area museum officials to pick out the one thing they could call their favorite. Each of their stories tells you something about them, their work and the vast array of preserved treasures tucked away in our communities.

1944 dress white Navy uniform

Chosen by Kelita Thomas

Lee County Museum

By Dana Frank

Lee County loves its military veterans. You can see it at Veterans Honor Park, just north of U.S. 290 and east of downtown Giddings, where flags, paver stones and an honor wall pay tribute to those from the county who are serving, or served, in the U.S. military.

The county also cherishes its history. All of that brings us to the Military Room at the Lee County Museum, where uniforms from all military branches, most worn during World War II, are on display. All were donated by Lee County residents.

Kelita Thomas likes to linger here. She has an affinity for the 1944 Navy dress white uniform bearing a lieutenant’s insignia and several medals that were worn by M.F. Kieke of Lee County. Thomas, the museum’s curator and president of Lee County’s historical commission, says she grew up “an Army brat” who is “very proud to be from a military family.” She always looked up to her older brother, Michael, who served in the Navy in a ship’s engine room.

“He has always been my hero,” Thomas said. “This uniform makes me think of my brother and all the other brave sailors who do so much to serve our country and keep us safe.” The man who wore the uniform on display was born in 1911.

Kieke was aboard the USS Missouri on Sept. 2, 1945, when representatives of Japan signed surrender documents to the Allied Powers to end World War II. Kieke interrupted his career as an attorney in Lee County to serve his country from 1944 to 1946. His uniform bears an Asiatic Pacific Campaign Medal, a World War II Victory Medal and an honorable discharge emblem.

Thomas, who is also tourism director for the Giddings Chamber of Commerce, was instrumental in creating the Military Room in July 2021 to correspond with the Giddings Sesquicentennial and the opening of Veterans Honor Park and memorial.

Other uniforms in the museum’s Military Room include a U.S. Cadet Nursing Corps uniform and an Army uniform from World War I. The oldest item in the room is a sword from the Civil War, and the “prize of the collection,” Thomas said, is a World War I German water-cooled machine gun.

The Lee County Museum is housed, along with the Giddings Chamber of Commerce and Visitor’s Center, in the two-story Greek Revival–style Schubert-Fletcher home, which August Schubert built in 1879 for his wife and 10 children.

The Baylis Fletcher family bought the house in 1900, and donated it to the Lee County Heritage Society in the mid-1980s. The society donated the home to the county in 2017. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In addition to the Military Room, the front room of the museum displays the home’s original formal furnishings and décor, including the Schubert-Biar family piano and a framed painted Fletcher family tree that dates the family’s roots more than 900 years to 1066. A bedroom and kitchen are also part of this exhibit.

Completing the museum, which Johnson estimates contains 5,000 pieces, are a rotating exhibit and the Lee County History Room.

Kieke was raised in Lee County and went from practicing law to become Lee County Attorney in 1950 and county judge in 1953. He died in 1980 at age 69.

It is fitting that Giddings’ former city slogan, “Home of Opportunity,” was coined by his daughter, then-schoolgirl Twila Kieke. (Today’s city slogan is “Experience Hometown Hospitality.”)

Twila came up with the slogan in a 1950 competition and pocketed $10 for her idea. Perhaps her father’s life of military honor, hard work and success served as inspiration for her winning idea.

Lee County Museum

- 183 E. Hempstead St.,

- Giddings

- 979-542-3455

- Open 10 a.m.-5 p.m., Monday-Friday

- Free admission; donations accepted

Early 1900s custom-made saddle

Chosen by Mike Vance

Brenham Heritage Museum

By Dana Frank

A custom-made saddle allowed a young Dr. W.F. Hasskarl to make house calls after his 1910 arrival in Brenham.

He quickly discovered he was not the only doctor in town, and most rural doctors of that era used carriages or horseback to get to the homes of patients. Cars were a rarity on the region’s dirt roads, though Hasskarl did get a Model T soon after his arrival in town.

To smooth horseback house calls, Hasskarl went to venerable Schramm Saddlery on Main Street in downtown Brenham. The business operated from the late 1800s through World War II. The craftsmen there created a sturdy dark-leather riding saddle that could accommodate medical supplies and equipment.

The well-used saddle, still in beautiful shape after a century, is part of the collection at the Brenham Heritage Museum in Washington County.

“It’s clear that the family took care of it,” said Mike Vance, executive director of the museum. “And we’ve made sure to protect it since it was donated by the doctor’s family a few decades ago.”

The saddle is a favorite of Vance’s because, he said, “It comes with a story that touches on a longtime business and an important family in town.” Vance is also a historian, an author and a documentary filmmaker.

The doctor’s son, Dr. W.F. (Boy) Hasskarl Jr., recounts in his memoir, “Remembering Brenham,” the story of his father and the saddle.

The saddle has a deep and comfortable cantle, which is the back of the saddle seat, to support the doctor’s hips and lower back. Behind the cantle, a wide, sturdy skirt secured saddlebags filled with medical supplies and necessities. The saddle’s stirrups are large, heavy and covered in thick leather. They offered stability and protection on Hasskarl’s rides through brush and branches, as well as some insulation on chilly middle-of-the-night rides.

The elder Hasskarl, a graduate of the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, was one of Brenham’s and Washington County’s most beloved doctors for decades. He was eventually joined by his son, who was born in Brenham and also graduated from the Galveston medical school. W.F. Hasskarl Jr., affectionately known as “Dr. Boy,” joined his father and a family friend, Dr. Thomas Giddings, at a medical practice that became the Brenham Clinic. The elder Hasskarl died in 1955 at age 70.

Dr. Boy, who served as an Air Force surgeon in the Korean War, worked as a physician in Brenham for 50 years, served two terms as the city’s mayor and was the Washington County health officer for 20 years. He died in 2008 at age 91.

The saddle will sit in the Brenham Heritage Museum space when renovations there are complete. The museum’s home is a 1916 former federal building and post office downtown that is expected to reopen to the public in September.

“Our goal is to create the best regional history museum in Texas,” Vance said. During renovation.

Brenham Heritage Museum

- Exhibits temporarily on display at Bus Depot Gallery, 313 E. Alamo St., Brenham

- Permanent facility, Post Office/Federal Building, 105 S. Market St., closed for renovations (completion expected in September 2022)

- 979-830-8445

- brenhamheritagemuseum.org

- Open 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Saturdays; Monday-Friday by appointment only

- Admission free for members, $5 for nonmembers; donations welcome

Early 20th century bogus medical device, the Nerv-O-Meter

Chosen by Rox Ann Johnson

Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives

By Dana Frank

Feeling nervous and jittery? Worried about ... all of it? Considering a curative route but first need a diagnosis? Have we got the gadget for you.

Come see the Nerv-O-Meter at the Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives in La Grange. It is a favorite item of Rox Ann Johnson, an archivist and curator at the museum. The device is a splendid example of the many quack medical devices that became popular in the early 1900s.

The Nerv-O-Meter purports to gauge your “nervisity” (no, that’s not a word) in milliamperes with the help of its accompanying diagnostic instrument, the “micro-quantumeter” (also not a word). The device has an additional tool that, though important-looking in its briefcase-like container, has unstated powers.

During the early 1900s, the medical industry was essentially unregulated and devices like the Nerv-O-Meter were all the rage. Many purported to cure almost any malady, from arthritis to baldness to “neurasthenia,” a not-quite-real condition with symptoms of exhaustion, headache, irritability and general neuroses.

The bogus medical devices, often used by quack medical practitioners, varied in appearance and function and went by colorful names, including The Rejuvenator, violet ray wand, magneto and the Elec-Treat Mechanical Heart, according to reports and advertisements from the time. The devices often delivered low-level electric currents from custom batteries, because, in the early 1900s, electricity, magnetism and even radioactivity were touted as having curative properties.

The Nerv-O-Meter was used by a chiropractor whose office was above the Mohrhusen-Schmidt company, a furniture store at the corner of Main and Colorado streets in La Grange in Fayette County. “The store owner who found these instruments above his business many years ago cut the wires so that his children didn’t hurt themselves,” Johnson said. “Evidently, they liked to play doctor with them.”

The Nerv-O-Meter and its briefcase tool are labeled with the name Fred Besuzzi of Los Angeles. According to a 1955 false advertising lawsuit, Besuzzi was a businessman who loaned money or credit to licensed chiropractors “to enable them to open or buy offices and equipment under the association name of Basic Diagnostic Office.”

The device’s components were added to the museum’s collection more as an oddity than anything historical, Johnson said. “I could only speculate as to how old they are. My take is that they are pure quackery, but what do I know?”

Johnson and her colleague, Maria Rocha, design and create the museum’s exhibits and events. Not all holdings are on display, so if you visit when the Nerv-O-Meter is on hiatus, just ask to see it.

Don’t let the Nerv-O-Meter mislead you, though. The Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives is a research space, with worktables and more than 16,000 historical images in its research collection. It also holds over 17,000 files, documents, scrapbooks, maps and other written materials.

Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives

- 855 S. Jefferson St. (above the library), La Grange

- 979-968-3765 (ask for museum and archives)

- cityoflg.com/library (click on Museum & Archives)

- Open 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Friday; 10 a.m.-1 p.m. Saturday

- Free admission; donations accepted

1800s Czech hymnal, smuggled in a loaf of bread

Chosen by Christine Campbell

Burleson County Czech Heritage Museum

By Denise Gamino

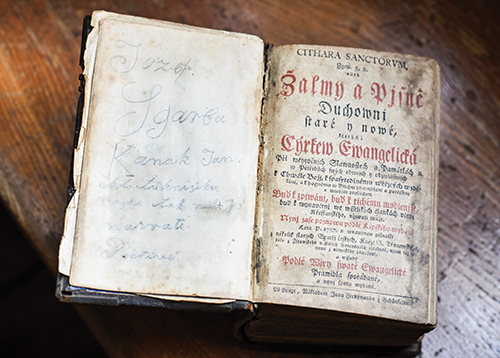

The thick brown book had no ticket to ride.

Instead, the vintage Czech holy book that is a Burleson County treasure is believed to have been smuggled out of Europe from what is now the Czech Republic in the 1800s. It was a time its people lived in servitude and their culture was suppressed under the strict Austrian-Hungarian Empire.

The stowaway full of songs and psalms apparently traveled inside an unconventional hiding place: a loaf of bread, according to its provenance document at the Burleson County Czech Heritage Museum and the family who donated it.

If the Protestant holy book had been found by the Empire, it would have been burned. An escape route of more than 5,000 miles brought the hymnbook to its display spot in Caldwell.

Museum president Christine Campbell says the Czech hymnal once considered contraband proves how important religion and culture were to the Czechs who left Europe for Texas.

“My favorite thing at the museum is our Czech hymnal,” she said. “The safety that our Czech ancestors risked to bring these important pieces with them sends a clear message of how important their faith was. We all have a lineage of something. To have a lineage of faith is a beautiful thing.”

Czechs began moving to Texas in the mid-19th century, mostly from Bohemia and Moravia. A 1906 Czech guidebook to a London exhibit about Bohemia states, “Three books are of striking importance and significance in the spiritual and moral development of the Bohemians: The Bible, The Postilla (Bible commentaries), and the Hymnbook.”

The chunky hymnal — 4 inches thick, 7 inches tall and 4.5 inches wide — is titled “Psalms and Hymns, Meditations.”

The publishing date is not known, but it’s signed by three men, including Jan Kanak. He wrote a note in the book: “Whoever finds this book should virtuously return it.”

John Orsag, an engineer retired from NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, is a descendent of Kanak. He grew up in the Czech community of Hrozanka in Burleson County, east of Caldwell, where his parents spoke Czech. His mother, Ella (Zalmanek) Orsag, had a cousin who was a great-great-great grandson of Kanak. He gave Ella Orsag the smuggled Czech holy book because he had no children. About 10 years ago, John Orsag and his two sisters (Emily Orsag Hejl and Joyce Orsag Floeck) donated the book to the Czech Heritage Museum.

“We just decided that would be the best thing to do with it,” John Orsag said. “It was always passed down with the story about how the Bibles were oftentimes baked in bread just to hide them in a place where the authorities were not expected to find them so they could bring them over (to America) and keep them from being destroyed.”

Thadious Polasek, a Czech language instructor at Blinn College in Schulenburg and director of Schulenburg’s Public Library, translated portions of the Czech holy book.

“If, under Austrian-Hungarian rule, the books were found, the owner would (have been) punished,” Polasek said. “Any book in Czech would have had to be hidden in the Czech lands. The people had to be creative — be it in a loaf of bread, be it in a secret compartment in the floor or the well or some secret area of the house — so they would not be discovered when Austrians were coming into the town or walking through houses inspecting for books.

“The goal of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire was to wipe out the Czech culture, to Germanize the people,” he said.

“If you were going to be leaving your home (to emigrate), what are you going to take with you? You’re going to take your Bible, your medical books,” Polasek said. “If they had to get it through customs as they were traveling through the Austrian territory or checkpoint, they had to come up with ingenious ways of hiding it.”

The Czechs’ success in smuggling out their sacred religious books shows “a very deep love of their faith, their culture, their heritage,” Polasek said. “They knew the way to preserve it was to keep the books with them.”

Burleson County Czech Heritage Museum

- 200 E. Fawn St., Caldwell

- 979-567-0000 (Chamber of Commerce)

- Call for open hours or to schedule a visit

- Free admission; donations accepted

1930s bench made in Bastrop State Park

Chosen by Nicole Deguzman

Bastrop Museum and Visitor Center

By Dana Frank

Natural spaces — how they feel, look, sound and smell — are a big draw for Nicole DeGuzman. That’s why she relocated a year ago from West Texas to Bastrop, to become director of the Bastrop Museum and Visitor Center.

“Bastrop and Buescher state parks are some of the reasons I moved here,” she said.

Her favorite museum item represents that natural realm because it was hewn and crafted from walnut at Bastrop State Park in the 1930s by members of the federal Civilian Conservation Corps, or CCC. “The rustic style of this bench was meant to match and blend with the landscape of the park,” DeGuzman said, “just like the buildings and cabins, many of which are still standing.”

The simple wood bench was made before U.S. national park furniture design became standardized. “It is rare that the piece has survived intact,” DeGuzman said. The bench was loaned to the Bastrop County Historical Society in 1996 by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

The hardworking bench isn’t glossy or flashy, and it is sturdy to this day. Museum visitors sometimes sit on it to gaze at exhibits, unaware they are sitting on a piece of Bastrop County history created by a Great Depression jobs program.

DeGuzman’s beloved bench has cedar cousins in the museum: a dining table and three chairs, all in the rustic style that harmonizes with the Lost Pines environment. The furniture at the museum was used in the park’s Refectory, or dining hall.

“A good portion of the original 1930s CCC-made furniture is still at the park,” according to Sally Baulch, the chief curator of the State Parks Cultural Resources Program at Texas Parks and Wildlife.

In the 1930s, President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal offered jobs to young unmarried men between ages 18 and 25 as part of the CCC to build out Bastrop State Park — as well as more than 800 other state and national parks.

Between 1934 and 1937, the Bastrop State Park furniture shop and mill turned out an estimated $75,000 worth of furniture for cabins and other buildings for parks nationwide. In today’s dollars, that is about $1.5 million.

That historic woodshop is still in use today. The brown signs familiar to visitors at any of Texas’ 89 state parks, historic sites and natural areas are made there. Bastrop State Park’s legendary handiwork now leaves a mark all around Texas.

Bastrop Museum and Visitor Center

- 904 Main St., Bastrop

- 512-303-0057

- bastropcountyhistoricalsociety.com

- Open 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Monday-Saturday

- Admission $5; free for 12 and younger and veterans

By Pam LeBlanc

I'm sawing away like a lumberjack with a handmade bow, its cord wrapped around a wooden spindle. My arms pump furiously as I try to coax an ember from a piece of wood.

Making fire using nothing but a few sticks and a cord isn’t easy. I could walk to a convenience store and buy a lighter by the time a single sunflower seed-sized ember drops from my “fireboard” onto a waiting piece of bark.

The convenience store route would defeat the purpose of the day, anyway.

I transfer the glowing bead into a thumb-sized indentation in a bundle of fluffed-up cedar bark and blow gently. It bursts into a tiny tongue of flame. I puff a little more, and it gets bigger. And as it grows, a bolt of confidence sizzles through my soul.

“I do think one of the coolest things you can learn to do in life is go out into the woods without a tool in your hand and make fire,” says Dave Scott, founder of Earth Native Wilderness School in Cedar Creek, west of Bastrop, where I’ve come for half a day to learn what it takes to survive in the wild without the trappings of modern-day life.

I have to agree with him.

But there’s more to surviving in the wilderness than making fire. By the time I leave this afternoon, I’ll know not only how to make fire, but also how to stay warm, hydrated and fed if I’m ever away from the comforts of home with nothing but my instincts, a couple of tools and these lessons.

Meet the expert

Scott, 41, opened Earth Native Wilderness School in 2011. It occupies 58 acres of wooded land west of Bastrop. The school offers programs for children and adults who want to learn how to live off the land or special skills. About 3,000 people — young and old — sign up for instruction or go to camps every year. The majority of the action is at the Earth Native campus, but there are some activities at Garey Park in Georgetown and McKinney Falls State Park in southeast Austin.

“It’s just people who like being outdoors and want to increase their skills or learn more about what it takes to take care of themselves in the wilderness,” Scott says. “We don’t get a lot of paranoid people, but with COVID and (2021’s statewide) winter storm, we are hearing from people who feel more vulnerable.”

The school’s style of wilderness training is more about learning confidence and enjoying time in the outdoors than about preparing for an apocalypse. Survival, Scott says, requires a steady disposition, some basic skills and an adjustment to an individual’s comfort level.

Scott grew up exploring Williamson Creek in South Austin. After his father bought land in Colorado, Scott spent summers there, rambling around in the forest. After his father joined a search and rescue team, Scott listened to emergencies unfold over the sheriff’s radio. When he was old enough, he trained for search and rescue work himself. After five years as a U.S. Army police officer, he spent three years training in wilderness survival, then became a survival skills instructor and eventually opened his school.

“I think the combination of my love of nature and wanting to be self-reliant made me to want to learn more about what it takes to take care of myself in the wilderness,” he said.

Lesson 1: Be prepared

The key to wilderness survival, Scott says, is planning ahead so you don’t find yourself in an emergency empty-handed. That’s why he carries a few basic items in his vehicle (see his list, Page 20C) to carry when he ventures into the wild: a small knife, something to start a fire and a water filter.

Still, emergencies happen. When they do, it’s important to stay calm. Take some deep breaths and quiet your mind.

There are three basic needs you must attend to: body temperature, food and water — or what Scott calls the survival triangle.

He makes it sound simple: “To me, the whole act of survival is problem-solving.”

Lesson 2: Not too hot, not too cold

Are you cool enough? Or warm enough? Can you maintain a comfortable body temperature with the clothing and shelter you have? If not, you should address this first.

If it’s hot, stay out of direct sunlight. Seek shade. Even better? Dip yourself in a creek if there’s one nearby.

If you’re cold, look at the materials around you. Try stuffing dry leaves inside your shirt to create a layer of insulation.

If you need to sleep, don’t lie directly on the ground. Lay down a bed of boughs first. You can also build a rudimentary shelter using branches and leaves, but that may not be necessary. Even finding a wind break or making one out of dirt or rocks can help.

“People think of shelter as a grand thing with a roof and fire, but that’s so much work,” Scott says. “More practically, prepare ahead of time. Carry lightweight things like a sheet of plastic to use as a wind block. And remember that movement and exercise help keep you warm.”

If you need fire to stay toasty — or to cook food or boil water — use what you have available to light it. Maybe you packed matches or a ferro rod, which is a small metal rod that sheds sparks when scraped with a knife (a good item to carry when backpacking). First, set dry, small twigs on fire, then work your way up to larger materials. Flat sticks burn better than round ones, and tree sap makes a good accelerant. Remember that flames burn upward, so start the fire from the bottom.

Creating a fire with the bow drill method I used takes practice, but it’s not impossible. From start to finish, it took me about an hour. Start by preparing a tennis ball-sized nest of shredded dry bark (I used juniper). Then you’ll make a fireboard by cutting chocolate chip-sized divots into a length of wood (we used a thick piece of trumpet vine). Next, carve notches leading from the divots to the edge of the fireboard.

After that, sharpen one end of a stick that is about an inch thick and a foot long to make a spindle. Then fasten a cord (use a natural fiber or vine if you don’t have a cord) to both ends of a curved branch (I used a juniper bough) to serve as a bow. Last, find a block of wood about the size of a deck of cards to use as a “handhold.”

You’ll twist the spindle into the cord on the bow, place the tip of the spindle onto the fireboard and brace your arm against your body. Clamp down with the handhold, then start to move the bow back and forth.

It’s wobbly at first, but after a few minutes you’ll find a rhythm. If you’re doing it right, in a few minutes a fine dust will fill in the notch in the fireboard. If all goes well, the heat created by friction will carbonize that dust and create an ember.

Tap that ember onto a leaf or bit of bark below your fireboard, then carefully plant it inside the wad of fluffed-up bark and blow gently.

Voilà, fire.

Lesson 3: Food for energy

Once you’ve taken care of your body temperature, you need to think about replacing calories lost through activity.

Here in Texas, we’ve got lots of options. I followed Scott as he foraged around his property, choosing bits of plants like he was moving through a salad bar.

First, he plucked a ruffled green leaf from a dock plant and offered me a nibble. It tasted slightly tart and lemony. Then he pulled up a few wild onions. Cleavers, those sticky, low-growing weeds that feel like a cat’s tongue (I call it Velcro plant), can be cooked down like spinach. He calls wood sorrel the “Skittles of the woods” for its tangy zing. Dewberries, mesquite beans, wild blackberries and pecans are all tasty options, too.

Other plants can be used for medicinal purposes. He points out a toothache tree. Chew its leaves or twigs to numb your tongue. Crush the leaves of a small plantain (different from the bananas that go by the same name), and use it to treat insect bites or inflammation.

We also brewed tea, toasting up a pan of yaupon leaves for 30 seconds, then pouring hot water over them. It’s an acquired taste — nutty and earthy — but loaded with caffeine.

Of course, exercise caution to make sure you know what you are eating. Learn more about foraging for food in Texas with the books “Wild Edible Plants of Texas” by Charles Kane, “Foraging Texas” by Falcon Guides and “Common Edible and Medicinal Plants of Texas” by Wesley Adams.

For something heartier, look no farther than the nearest creek or lake. A plastic water bottle can be converted into a minnow trap. Just cut the top off and invert it, so minnows get washed in but can’t back out. You can eat them raw if need be, or cook them up over a fire. “The skin crisps up and the tail is good,” Scott chuckles.

Lesson 4: Don’t dehydrate

You need water to stay alive. If you didn’t bring a water bottle or filter with you into the outdoors, you’ve still got options, although there are fewer if you’re in a desert environment.

Use a rock or a hole lined with leaves to catch rainwater. If you have a container, boil the liquid over a fire to purify it. If you don’t, squeeze it through a T-shirt, then let it settle in the sun for at least six hours (longer if the sky is cloudy).

My favorite solution? Wild grapevine. It grows all over Central Texas and can be as thick as an adult’s arm. Cut through a section of thick vine, then put a container (or a rock with a hole in it) at each end. You can drain up to a liter (four cups) of water from a healthy plant.

Lesson 5: Keep calm and carry on

In the end, a level head will go a long way toward staying safe.

Stay calm and remember priorities. Don’t rehash whatever mistakes you’ve made to find yourself in a bad situation. You can analyze that later.

And don’t feel sorry for yourself. “In an emergency or real crisis, you can’t afford to do that. It’s not useful,” Scott says.

Instead, take a deep breath and keep it all in perspective. “Humor and the ability to not take yourself too seriously are the best survival skills of all,” Scott adds.

A little dollop of humor helped me make that fire and propelled me through the rest of my wilderness survival training. They are skills I hope I never have to use, but if I do, I’ll know it’s possible to survive out there — even without a lighter.

Vehicle essentials: Plan ahead to survive in the wild

If you are stranded — temporarily, hopefully — in a remote wilderness location, the best strategy is to have planned in advance for the unexpected. Dave Scott, the founder of Earth Native Wilderness School west of Bastrop, recommends stocking your vehicle with these supplies in case you ever find yourself in such a predicament.

Vehicle gear

- Two flashlights

- Multi-purpose tool (Leatherman or something similar)

- Non-folding knife (Morakniv makes good quality inexpensive knives.)

- Extra weather-appropriate clothing: long-sleeved sun shirt, hat in heat; insulated jacket, knit cap, gloves in cold.

- Emergency water — 2 gallons

- Battery jumper pack: Scott prefers these to jumper cables because you aren’t reliant on another vehicle. Make sure to get one large enough to jump your battery. If you have a truck or large SUV you need a more powerful one than if you have a sedan. Small pack to carry if you need to leave your vehicle (see list below)

- Good first aid kit (such as Adventure Medical Kits’ backcountry version)

- Sleeping bag or wool blankets in cold weather

- Lightweight water filter (such as Sawyer mini system)

- Paper road maps or map book (Gazetteer) of your state, nearby cities

- Emergency road flares

In addition to the gear in your vehicle, keep a small, dedicated emergency pack, like a fanny pack with a shoulder strap, as an emergency tote. Stock it with these items:

Tools

- Quality non-folding knife

- Compass

- Multi-purpose tool

- LED flashlight with an on/off switch (one that will burn for many hours even if that means lower lumen power); two sets of extra batteries for light

- Folding saw, like a Silky Pocketboy

Fire

- Two to four fire-starting options (hurricane matches, lighters)

- Fire starters, like fatwood

Shelter

- Emergency ponchos

- Three thick, extra-large trash bags for use as a wind break or to pull over your body

- Lightweight small tarp (Scott recommends lightweight tent floor with webbing attachment at corners, or painter’s plastic if you can tie a sheet bend knot)

Water

Iodine or similar water purification tablets

Two clear, 2-liter water-carrying bags

Stainless steel water bottle

Food

- Small amount of high-calorie food (Scott recommends 500-1,000 calories a day)

- Sugar and salt packets

- Emergen-C or other electrolyte replacement

Additional items

- Mini first aid kit

- Extra pair of prescription glasses

- Small amount of prescription medication if critical 30 feet of paracord rope

- Several gallon-size Ziploc bags to keep items clean, dry

- Whistle

- Signal mirror

- Small fishing kit (think small pill-bottle sized with hooks, line, weights and maybe a synthetic worm or small lure)

- Pencil notepad (Write in the Rain makes a waterproof pad)

- Some flagging tape to mark route on trees, branches if you leave vehicle

EARTH NATIVE WILDERNESS SCHOOL

137 Woodview Lane

Bastrop, Texas, 78602

earthnativeschool.com 512-299-8870

COURSES INCLUDE:

- Two-day Wilderness Survival 101 for adults includes strategies for surviving emergencies, fire lighting using friction; basic shelter building, finding edible/medicinal/useful plants; water collection and purification, food/foraging techniques, knife/tool use and more; $245

- Individual day or weekend adult skill courses include land navigation, wildlife tracking, basket making, edible/medicinal plants and more; from $45 to $245

- Ongoing adult intensive courses include wilderness survival, wildlife tracking; one weekend a month for 8 months; October-May; $2,495 to $2,995 (payable in installments)

- Youth classes, ages 5 to 16, include Wild Outside weekly class throughout school year; $1,995 (payable in installments); and individual one- and two-day weekend classes; about $55 a day

- Preschool classes, ages 3½ to 5, one- or two-day a week programs at Wild Life Forest Preschool; monthly and one-day weekend classes during the school year; prices vary

- Summer camps include five-day sessions at three locations: Earth Native's campus in Bastrop, McKinney Falls State Park in southeast Austin or Garey Park in Georgetown, $375; five-day overnight camps at Earth Native campus in Bastrop. $695; camps are full this summer