Scam alert: Members report increase in fraud attempts

Recent news

Story by Kristin Finan

When Mark and Sunny Woelfel settled onto 3 acres of family land in Giddings in 2014, it was clear they were right where they were meant to be. “It was always a lifelong dream to move to Grandpa’s place,” said Mark Woelfel, a Bluebonnet member.

But as they researched ideas for building a home on the Lee County property, they were drawn to a particular concept: the “barndominium.” The word, popularized in the 1980s, is the name given to the transformation of a barn-like space into a home. In recent years, barndominiums are often built from a variety of metal-frame buildings.

After removing an existing mobile home from the property, the Woelfels spent a year living on-site in an RV with three of their five children — the other two are adults who visit frequently — while the home was built. Last summer, they moved into their new Pinterest-worthy, two-story 3,200-square-foot barndominium, which centers around a sprawling great room and is adorned with lovingly restored furniture that has been in the family for generations.

It was custom built by Exner & Snyder Custom Homes. The company, based in Giddings, works on both barndominiums and traditional houses across the Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative service area. Both styles of homes average about $135 per square foot, said owner and founder Jonathan Snyder of the company. The Woelfel house, however, cost roughly $100 per square foot to build.

The concept of barndominiums (“barn” plus “condominium”) is not new. Rural homeowners have transformed wood or metal barn structures into living spaces for generations. In recent years, however, thanks to websites like Pinterest and home design shows such as Chip and Joanna Gaines’ HGTV series “Fixer Upper,” (which first featured a barndominium in 2016), the trend has gotten bigger and grander.

Stacee Lynn Bell, aka “The Barndominium Lady,” has designed nearly 150 barndominiums across the country, including some being constructed in the Bluebonnet area.Bell, who is based in the small East Texas town of Cleveland 45 miles northeast of Houston, said that in the South, especially in Texas, “barndos” are typically steel-frame structures that often include a workshop or garage. They can be built within an existing metal structure or completely from scratch. They generally feature a metal, rectangular frame that has been finished out on the inside, meaning the inside has the feel of a traditional house but is centered around an open-concept great room. In other parts of the country, she said, wooden “pole barns” or engineered wood frame structures are more common. The exteriors of barndominiums can vary greatly, ranging from a traditional, barn-like feel to a more modern metal façade.

Although the barndominium trend is nationwide, it is especially popular in Texas, Oklahoma and Georgia, the website barndominiumlife.com states. Although the cost of building a new metal-frame home tends to be comparable to that of a basic wood-frame home, people are drawn to the aesthetics of barndominiums and the fact that their design – which typically features energy-efficient windows, lots of natural light and spray-foam insulated walls and attics – can be as energy efficient as their wood counterparts. They are also more durable and resistant to heat, weather and pests than wood-frame structures, said Elliott Lukasik, owner of Pristine Designs, which creates floor plans for about a dozen home builders in Central Texas.

Lukasik, who has been drawing floor plans for 28 years, has been asked to design metal-frame homes since the early 2000s. He didn’t regularly start hearing the word barndominium until seven or eight years ago. These days, he said, nearly half of the 100 plans he draws each year are for barndominiums, and most are in the Bluebonnet area.

“Originally it was something really simple, something cheap to get into, something to live in. Now, some of the barndominiums are Taj Mahals, big and elaborate and really nice,” he said. “If you think you’re living in a barn, it’s really not a barn. These can be more expensive than doing a conventional wood-frame build. It’s really what you want to put into it.”

Most Texans opt for metal frames rather than wood frames, in part because they like the look, Lukasik said. For do-it-yourself projects, metal-frame home kits are easier to assemble than wood-frame kits.

The average barndominium buyer is looking for a home in the 1,500 to 2,200-square-foot range, although some go as big as 4,000 square feet. The most requested plan is a one-story rectangular home, Lukasik said, but upstairs lofts are also popular.

Snyder of Exner & Snyder Custom Homes has seen demand for barndominiums increase in the past 15 years.

The company works on six or seven barndominiums a year, concentrating on the area between Brenham and Bastrop. “The lending was really hard to get on them before, because the banks didn’t know what to do with them as far as taxing and values on the building, but they’ve become a lot more mainstream on the market,” Snyder said.

They are popular in part because metal exteriors allow for less upkeep (you don’t have to paint them, for example) but the interiors allow for greater creativity.

“You start out with a big main structure and then really you can build anything you want on the inside,” he said. “They can be simple buildings, but they can be super extravagant on the inside. It’s really about your imagination.”

Most of the houses take 6 to 8 months to build, Snyder added. “We are a complete custom builder, so we are customer-first driven,” Snyder said. “We sit down with the customer to help them envision what they want and make sure they get the product they envisioned.”

Bluebonnet member Kathy Anderson and her husband, Jay Anderson, are building a barndominium outside Giddings with the help of Exner & Snyder. They expect their 2,200-square-foot home to cost around $300,000. The couple will live next door to Kathy Anderson’s sister.

“It took me a long time to find a floor plan for what we wanted,” said Anderson, who hopes to eventually add a large garden, chickens and a small orchard on the property. “You want to maximize your best views. Don’t be afraid to draw it out on paper and ask a lot of questions. I had my notepad with me all the time. Think of questions and shoot them over right away.”

Bluebonnet member Christa Wilson, who lives in Cypress near Houston, dreamed of building a place where she and her twin sister, Corrin Wilcox, could retreat with their families on weekends. After falling in love with Brenham, the sisters purchased 7 acres there to build a traditional house they could share. Then they watched the “Fixer Upper” barndominium episode in 2016 and changed directions.

“We wanted the big grand room that had everything,” said Wilson, who has five children. Her sister has three children. “We wanted a space for our family to hang out. It’s like a party barn pretty much.”

Wilson and Wilcox, both former teachers turned stay-at-home moms, decided to be their own general contractors, purchasing one large red metal building frame from Mueller, Inc., a West Texas-based steel manufacturer with 33 locations across the Southwest. Construction of the building — which includes 4,000 square feet downstairs, half of which is the great room, and 1,000 square feet upstairs — took about four months.

The barndo, which also includes a 1,500-square-foot covered patio, was ready in January 2017. Since the house can sleep 28 people, Wilson and Wilcox decided to rent it out when they weren’t using it. You can get a taste of their barndo life by booking a stay on their website, 12armadillos.com, or by searching “barndominiums” in Central Texas on home rental websites Airbnb or VRBO.

Amanda Hart embraced the barndominium life well before it became a trend. She and her husband, Jon, a Bluebonnet member and welder, started hand-building their first barndominium on their 10-acre property in Winchester in 2005. The initial structure was 26 feet by 50 feet, half of which the couple enclosed to be their home, which they moved into in 2007. The couple used the other half of the building as a welding shop.

“It was literally going to be a barn and a shop, but then we decided, ‘Why have this big space and wait to build a house later when we could just make this our house?’ ” she said.

After their family expanded to include three kids, they enclosed the rest of the 26-by-50-foot structure for living space and started an 18-by-36-foot add-on completed in 2019. They also added a back porch, carport and another bathroom.

“We had a kitchen and a living room, but we didn’t have anywhere to sit down and eat as a family,” she said. “We wanted to be together and we needed the additional space to be able to do that. I love it. To be able to do it yourself really gives you another level of appreciation for what you have.”

Hart estimates that hiring a contractor for the work would have cost twice as much.

Bluebonnet member Dawn Hedgpeth and her husband, Jesse, also plan to embrace the do-it-yourself barndominium approach, downsizing from a 3,500-square-foot house in Dickinson, 30 miles southeast of Houston, to live temporarily in a 320-square-foot shed-house on 8 acres in Bastrop. They purchased the property because it has an empty 2,000-square-foot metal building they plan to convert to a barndominium over several years.

“We’re hoping to do most of the work ourselves,” she said, but they are working with Tello Welding and Construction of Giddings on the project.

The estimated cost for their property and construction is about $300,000. The Hedgpeths have been interested in barndominiums for more than 20 years and are excited to work on the project. After living through hurricanes on the Gulf coast, Dawn Hedgpeth can tile and build cabinets.

“We’re in our mid-50s. We could just as easily buy a little condo somewhere and have money set aside and travel, but this is an adventure, and we like doing this sort of stuff together,” she said. “We get to do something together and say, ‘Look what we did. This is ours. We built it.’

Area builders in and near the Bluebonnet service area

- Texas Barnodminiums

- Exner & Snyder Custom Homes (512-304-8928)

- Tello Welding and Contruction (979-716-0343 or Facebook)

READ UP: There are multiple books about barndo designs and layouts online, or read “Barndominium Lifestyle,” a bimonthly magazine.

ON THE WEB: There are Facebook groups dedicated to barndominiums, including “Texas Barndominiums,” “Barndominium Homes” and “Barndominium Life” (by barndominiumlife.com). Texas Barndominiums has a YouTube channel where you can learn more.

Home Kits, a do-it-yourself option

Folks who want to build a barndominium but are on a budget may opt for a home kit.

What does a home kit include? Typically a floor plan and prefabricated components to build a one-, two- or three-bedroom home including a bathroom, great room, kitchen, dining room and laundry room.

How much does it cost to build a barndominium using a kit? Barndo home kits can be significantly cheaper than building a traditional home or hiring a contractor if you do it yourself.

Pros: If you plan to hire help, expect to pay a general contractor less if you use a home kit. Kits cut construction time as well as labor and building costs.

Cons: Home kits and what they include vary from company to company, so do a lot of research. Even if you plan a DIY, you’ll likely need to hire subcontractors for items such as a septic system, plumbing, electrical, fireplace and HVAC. On average, expect to pay $60 to $135 per square foot with a home kit.

Where to buy: A few Texas-based companies that offer home kits are General Steel Corp., Absolute Steel Texas, Capital Steel Industries, Mueller Inc. and Texas Barndominiums.

Sources: barndominiumlife.com and gensteel.com

Download this story as it appeared in the Texas Co-op Power magazine »

Story by Denise Gamino

Photos by Sarah Beal

Bridges link us together, connecting what divides us.

They span time. They span space. They span history.

Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative’s region is dotted with bridges — old and new, small and large, well used and little traveled. We’ve highlighted a collection of area bridges that have colorful histories, interesting sights or good backstories. Two of the bridges no longer exist, so their stories are relegated to history. You can safely idle on the remaining bridges in these pages, then perhaps take a short drive or day trip and see them yourself.

1. Plum Creek bridge, Luling

Caldwell County

New York City has its famed High Line, an elevated old rail line transformed into a 1.5-mile pedestrian park that puts visitors at eye level with billboards and Manhattan apartment windows.

Luling offers a rural version of a miniature high line with the historic 1931 Plum Creek highway bridge that’s been preserved for pedestrians on the southeast edge of town. Visitors can walk high above rippling Plum Creek and stand eye to eye with the tree canopy. Pecans and bur oak acorns hang close at hand on adventurous branches that stretch into the bridge space, creating a green privacy curtain that can envelop visitors in summer.

The quarter-mile, dead-end bridge — which is now closed to vehicle traffic — is on the National Register of Historic Places.

It once served as the U.S. 183 bridge for travelers between Luling and Gonzales. But in 1999 a new highway opened next to the Depression-era bridge, and it went into retirement. Now it hides in plain sight, but most U.S. 183 motorists don’t even give it a glance.

The bridge looks like it doesn’t get much foot traffic, even though a welcoming sidewalk behind a Best Western hotel leads straight to it. These days, there’s a more popular draw just across nearby Interstate 10 — a large, crowded Buc-ee's convenience store with dozens of gas pumps.

Next time, opt for the solitude of the trees.

2. Black Bridge, Dime Box

Lee County

Someone in Dime Box recently asked retired Lee County Clerk Carol Dismukes a simple question: “What is that bridge doing here in the middle of town? There’s no water under it, and it doesn’t go anywhere."

The old, black iron structure perched unexpectedly in a park in Dime Box is “part of the history of Dime Box,” Dismukes said. “So many of the old-timers fondly remember that bridge.”

Around 1912, the single-span bridge was erected on private property about a mile east of Dime Box. The Houston and Texas Central Railway put the bridge on the farm of Asa Moses after he complained that railroad tracks cut his property in half, making it difficult for livestock and farm equipment to traverse his land.

The bridge, which became part of a county road, quickly became a popular place for courtship.

But by 1991, the bridge was abandoned when a new county road was built, so the Union Pacific Railroad arranged for a company to haul it away as scrap. However, the Dime Box Lions Club wanted to save the beloved bridge.

“We finally convinced (the metal recycling company) that we would move it if they would give it to us,’’ said Dismukes, club secretary.

The bridge, always known locally as Black Bridge because of its coat of paint, was moved in 1998 to land next to the Dime Box SPJST Lodge.

In 2015, the Lions Club moved it again to a park it had created one block from the main intersection in Dime Box (Stephen F. Austin Boulevard and Bowers Street). The inoperative bridge is in Black Bridge Park, at Bowers and Stewart streets, along with picnic tables, a historic oilfield pump jack and a volleyball court.

Wood planks are long gone, but the Lions Club is raising money to install a new bridge deck so pedestrians can walk across the bridge to nowhere.

“The bridge is important to the community,” Dismukes said. “It has meant a lot to be able to keep it."

3. Meadow Creek Lane covered bridge, near Chappell Hill

Washington County

In the rolling hills of Washington County, a red roof tops an unexpected covered bridge that evokes a bygone horse-and-buggy era.

The bridge was a labor of love for Houston land developer Terry Ward, who grew up in Ohio and never forgot the covered bridges he explored on childhood trips through Amish country.

“They were so cool,” he said. “We would get out and stand on the bridges. Those really fascinated me.”

Ward spent boyhood summers on his grandparents’ farm and later collected books about covered bridges. He moved to Houston after college to work in marketing for the Astros, then switched to the food business and opened two Dirty’s restaurants in Houston before shifting to real estate.

After shepherding commercial developments, Ward began building residential communities in rural areas. He bought tracts and walked the land to gather inspiration on how to create long-term emotional ties between buyers and the countryside.

“I got my covered bridge books out and said, ‘This is where I can do something different and create a feeling.’ I want to touch somebody in their heart and soul. I believe the covered bridge is a huge piece to that.”

You can drive on the two-lane black top bridge at the entrance to the Meadows of Chappell Hill neighborhood on Meadow Creek Lane off FM 2447, about 2.5 miles northeast of Chappell Hill.

4. Birch Creek bridge, near Lake Somerville State Park

Burleson County

A historic one-lane bridge in Burleson County could be a fishing fortune teller for Lake Somerville-area anglers.

The 90-year-old bridge on County Road 146 about four miles northwest of Lake Somerville State Park crosses over Birch Creek. When the creek water is up, local lore says white bass could be spawning — and biting —here and in other lake tributaries.

It was built in 1931 by the Monarch Engineering Co. of San Antonio (although some records say it was built in 1940). Heavy storms in recent years — including a record flood in 2015 — forced closure of all or parts of Lake Somerville State Park, but this steel truss bridge with wood planks endures.

“You can tell how high the water is in the lake by looking at the level in that creek,” said Tommy Snow, who worked for 23 years at the state park as a police officer before retiring from the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

The bridge makes a popular background for photos of new high school graduates, soon-to-be brides and grooms, and families.

Ben Tedrick, IT engineer for the Bryan-College Station Eagle, likes to drive over this Birch Creek bridge on his way to Somerville Lake, where he documents his adventures in a video blog called FishTales.

“Birch is a seasonal creek and often dry that far upstream (near the bridge), but like most watersheds in this area, when it floods, Birch Creek becomes more like a raging river,” Tedrick said.

The bridge is safe but is scheduled for rehabilitation in 2023, according to the Texas Department of Transportation.

Other than anglers, not many people use the Birch Creek bridge. Only about 70 cars a day crossed the 80-foot bridge in 2010 — an average of three cars an hour, according to the most recent data available.

If you are one of those few, check out the bridge’s sloping shape, known as a camelback configuration. It is considered a rare bridge type today.

And keep an eye out for a bald eagle. They nest at the nearby lake and could be hunting around the bridge.

5. CCC stone bridge, Lockhart State Park

Caldwell County

The pretty little sandstone bridge in Lockhart State Park doesn’t get much traffic. It’s easy to miss the little dirt road on the left just after you enter the park, but it leads to a historic bridge over a tributary of Clear Fork Creek.

During the Great Depression, young men in a New Deal jobs program earned $30 a month to lift heavy rocks from a nearby private quarry to build the arched span. Government rules required them to send $25 of their paycheck home to family.

From 1935-36, Company 3803 of the Civilian Conservation Corps also built a refectory, dance pavilion, stone water tower, park residence and dam in the 264-acre park, where trees drip with Spanish moss.

Trees surround the one-lane bridge, which now is closed to vehicles. Its semi-circular arched form can be traced to the architecture of ancient Rome.

“This is the most beautiful bridge in the park, but unfortunately, it is all but hidden to the public,” park interpreter Lauren Hartwick said. “Few who visit Lockhart State Park notice this beautiful relic.”

After visiting the bridge, head to the park’s short Hilltop Trail (a third of a mile, one way) to find some Hercules’ club trees, also known as toothache trees. The conspicuous bark is studded with triangular points, so the trunk looks like a giant spiked collar. Before dentistry, the tree was a toothache remedy because chewing a twig or leaf can numb the mouth.

6. Demise of 1915 bridge across the Colorado River, Smithville

Bastrop County

Smithville’s second bridge over the Colorado River — built in 1915 to replace a 1900 steel bridge that was destroyed in 1913 by a flood — no longer stands. But it made a spectacular — and very loud — exit.

The 1915 bridge crossed over the river and connected to Smithville’s now Main Street, about one third of a mile downriver of the current bridge, which was built in 1948. Vehicles used the 1915 bridge until the 1940s, when a military bulldozer being transported over the bridge caused severe structural damage to the span.

After the military accident closed the 1915 bridge, vehicle traffic was diverted to a temporary floating pontoon bridge built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers just upstream from the damaged bridge. The unusual stream of floating traffic made for good viewing by locals, who regularly flocked to the riverbank for picnics to watch the parade of cars.

The obsolete 1915 bridge finally was destroyed on Sept. 8, 1950, by a planned detonation that sent the center span crashing into the river. Smithville photographer Fred Moree captured the bridge’s final moment as it made its free fall.

7. Old Congress Avenue bridge, Richard Moya Park

Travis County

If you want to know what it was like to walk across the Colorado River in Austin in the 1880s, a time when today’s Capitol was being built, head to an eastern Travis County park just south of Austin-Bergstrom International Airport.

At the far eastern edge of Richard Moya Park, you can stroll the wood planks of a steel bridge originally built in 1884 as the Congress Avenue bridge. Look closely to see “Carnegie” stamped into the metal in some spots, a 19th century memento of what was once the largest steel company in the world — Carnegie Steel Corp.

This bridge was originally built over an undammed Colorado River in the Texas capital city as a six-span, through truss bridge, meaning the trusses are above and below the deck. It was designed by King Iron Bridge and Manufacturing Co. of Cleveland, Ohio. In 1910, the six-span bridge was dismantled and put into storage, replaced by a new Congress Avenue bridge.

The pieces of the old bridge didn’t rest long. In 1915, three of its spans were used in a road bridge across Onion Creek at a low-water passage called Moore’s Crossing. It was in an agricultural community that today is part of Richard Moya county park near FM 973. The bridge lasted less than a year. It washed away in a flood, to the dismay of locals.

Undeterred, Travis County elevated the bridge’s support piers by about 10 feet and erected the remaining three spans at the same spot over Onion Creek in 1922. It stands today at 58 feet above the creek and is 537 feet long and 20 feet high.

It was closed to vehicles more than 30 years ago, but pedestrians can use it today. The bridge top has floral scrollwork that seems a good fit for its current spot in a pastoral park dotted in the spring with wildflowers. From the bridge, visitors can see stately pecan trees that once were part of a pecan orchard. Pecan hunting in the park is still a popular — and lawful — activity in the fall.

8. Collapse of the old railroad bridge, West Point

Fayette County

Ever wonder why a chaotic or disastrous situation is commonly referred to as “a train wreck”? Startling photos of an incident on a railroad bridge over the Colorado River in 1961 vividly illustrate that metaphor.

On May 26 that year, a 98-car westbound Southern Pacific freight train carrying steel, auto parts and other cargo derailed while on the three-span T&NO (Texas and New Orleans) railroad bridge just north of the community of West Point in Fayette County, 12 miles west of La Grange. The event damaged a portion of the bridge, which was later replaced.

The wreck plunged some boxcars into the river while about 30 cars crashed into a heap on the south river bank. The Fayette County Record’s dramatic photo package shows one boxcar dangling from the single intact bridge span while another car balances part way off the span.

Four diesel engines and 26 cars had already crossed the river safely, and the last 26 cars and caboose stopped short of the river on the north side.

“As the cars derailed, they piled up like so many sticks of wood against the third span,” according to the newspaper. Two of the three 200-foot bridge spans were knocked down, leaving the bridge “virtually demolished,” the newspaper reported on May 31, 1961.

Railroad officials said some 12-foot steel forms carried as cargo shifted position and hit the bridge as the St. Louis-to-Los Angeles train crossed the Colorado. It took 150 men and heavy equipment to clean up the wreckage.

Today, the repaired railroad bridge still carries Union Pacific trains over the river.

9. Henderson Park bridge, Brenham

Washington County

The hard-working pedestrian bridge over Higgins Creek in Henderson Park has served several tours of duty — spanning three centuries in three places.

This 80-foot, 19th century bridge bore horses and buggies, Ford Model Ts as well as Ford Mustangs, school buses and even heavy farm equipment during more than 100 years of roadway service in Washington County. It carried traffic over creeks in two different locations before being saved from the scrapyard. In 1995, it was put in this park, famous for hosting decades of Juneteenth celebrations.

Each wooden plank of this tireless bridge reverberates with history.

“Henderson Park has been a wonderful place for the Black community for years and years, back to the 1920s — bringing in all kinds of wonderful events,” said Eddie Harrison, a retired Army colonel and former municipal court judge in Brenham. Harrison was interviewed before his death in November, 2020, at age 89. “The annual (Black high school) football games, annual conventions and especially Juneteenth were held there every year. Thousands of people would celebrate and enjoy themselves.”

Harrison best remembered the performance of blues singer Lightnin’ Hopkins.

The bridge was originally built in 1890-91 by Missouri Valley Bridge and Iron Works over Yegua Creek south of Somerville on what is now Texas 36. It is believed to be iron, not steel, even though you can see “Carnegie” stamped on some struts, signifying the famed Carnegie Steel Corp. Traffic outgrew the bridge, so it was replaced by a two-lane bridge circa 1926. The original pin-connected bridge, with its beam framework, was moved to Tommelson Creek on Cedar Hill Road, then to an unpaved road in farmland about six miles north of Brenham.

Growth in the area continued, and in 1994, the bridge again was replaced by a sturdier two-lane model. The state highway department gave the historic bridge to the City of Brenham for use in Henderson Park over Higgins Creek.

“The subject bridge is now a rare artifact of late nineteenth century bridge technology,” according to a 1997 Texas Department of Transportation report. “It is also a physical manifestation of the products and business practices of a bygone age.”

Henderson Park was created in the segregated 1920s to serve the Black community. It is next door to Fireman’s Park, the oldest park in Brenham.

“Beginning in the 1880s the Juneteenth celebration was regularly held (on land that later became Henderson Park). The park was once home to a large pavilion that hosted dances featuring legendary musicians, including B.B. King, (Big) Joe Turner, Little Richard and Cab Calloway. The park was also home to all of the athletic events for the Black community and host to a semi-professional baseball team,” according to a Brenham city history.

“That bridge had no better place to go,” Harrison said.

Download this story as it appeared in the Texas Co-op Power magazine »

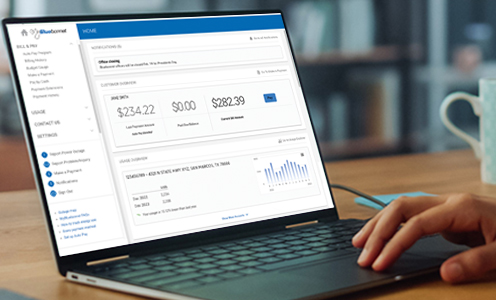

Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative offers several ways for members to seek help paying their bill. These self-service options are available 24/7 online, on the MyBluebonnet mobile app and through our automated phone system.

ONLINE

Our website offers information about payment extensions, local energy assistance providers and other helpful information such as a weatherization program that covers home improvements to reduce your power bill.

When you request a payment extension, you will be directed to log in to your MyBluebonnet account. If you haven’t yet registered for a MyBluebonnet account, on the login screen click “Sign up to access our Self Service site.” You can also click Register at the top of bluebonnet.coop. Once you’ve logged in, click on the Billing & Payments tab, then the Payment Extensions link.

This option gives qualified members an extension on the due date of their current monthly bill. The member must be past due only on their current bill, have applied within 10 days of the due date and have met the requirements of previous payment extensions.

If you are looking at bluebonnet.coop on a mobile device, you will need to log in to your MyBluebonnet account. Click on Billing & Payments, then Payment Extensions.

MOBILE APP

On the MyBluebonnet mobile app, log in and click on the Bill & Pay icon, then Payment Extensions. Click the small ‘I’ in the top right corner of the screen for more information about payment extensions. If you haven’t downloaded the new app, just search MyBluebonnet in Apple’s App Store or Google Play. Members can register for a MyBluebonnet account through the app’s launch screen. Click “Don’t have an account? Register now.”

BY PHONE

The MyBluebonnet automated phone system now offers members the option to request a payment extension. Call 800-842-7708, and once prompted, press 2 to use the automated system, then press 2 to request a payment extension.

Bluebonnet knows that the COVID-19 outbreak continues to financially impact many families and businesses. We do our best to work with members who need help with their electric bill. If these self-service options don’t meet your needs, call a member service representative at 800-842-7708 between 8 a.m. and 5 p.m. Monday through Friday.