Appliance heroes vs. hogs

Recent news

Bluebonnet and LCRA representatives present a $19,869 grant to the Heart of the Pines Volunteer Fire Department for new protective equipment. The grant is part of LCRA’s Community Grants program. Pictured, from left, are Kyle Ward, Mike Santucci and John R. Ertz, firefighters; Melissa K. Blanding, LCRA board member; State Rep. Stan Gerdes; Matthew L. ‘Matt' Arthur and Margaret D. ‘Meg’ Voelter, LCRA board members; Debbi Goertz, Bluebonnet Board member; Mark Mayo, LCRA board member; Elizabeth Ehlers, LCRA regional affairs representative; Roderick Emanuel, Bluebonnet Board Vice President/Vice Chairman; and Josh Thomas, Bluebonnet’s Bastrop-area community representative.

Heart of the Pines Volunteer Fire Department will soon purchase additional protective equipment to increase the number of firefighters who can safely respond to emergencies with the VFD, thanks to a $19,869 grant from Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative and the Lower Colorado River Authority.

The community grant, along with $5,159 in matching funds from the VFD, will equip four additional firefighters with gear such as special jackets, helmets and boots to fight wildland, vehicle and structure fires. Having more firefighters can help speed up response time and mitigate potential property damage, injury and loss of life.

“Without this grant, we would only be able to properly equip one of our four trained volunteer firefighters,” said James Lewey, Heart of the Pines VFD treasurer. “When something like a fire happens, our goal is to ensure that every trained first responder is able to quickly jump into action, and frankly new equipment can be very cost prohibitive.”

Heart of the Pines VFD provides emergency assistance to a 35-square-mile area in eastern Bastrop County. The department also provides mutual aid to other area departments and participates in Bastrop County wildland fire task forces.

“Because we are entirely made up of volunteers, there are times when our department receives emergency calls and not everyone will be able to respond,” Lewey said. “It’s vital that we have as many firefighters as we can that are properly equipped, and thanks to this grant we will be able to continue the training of four firefighters that will be able to respond.”

This is one of five grants recently awarded by Bluebonnet and LCRA through LCRA’s Community Grants program, which helps volunteer fire departments, local governments, emergency responders and nonprofit organizations fund eligible capital improvement projects in LCRA’s wholesale electric, water and transmission service areas. Bluebonnet is one of LCRA’s wholesale electric customers and is a partner in the grant program.

Applications for the next round of grants will be accepted in January. More information is available at lcra.org/grants.

Veterans from the Bluebonnet region share memories of service, sacrifice and returning to Texas

Story by Sara Abrego

Photos by Sarah Beal

Their stories continue long after their time in uniform.

On Veterans Day, Nov. 11, we honor the men and women of the Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative service area who served their country. They are neighbors, business owners, volunteers and mentors who carry their experiences from faraway posts into Central Texas life.

There are more than 1.5 million veterans living in Texas, more than any other state, according to a 2023 statement from the Texas Veterans Commission. They make up about 5% of the state’s adult population. More than 10,000 veterans live in the Bluebonnet service area, according to Census Bureau data.

To honor their service, we asked six veterans from the region to share their memories of decades in the military and how they continue to strengthen Bluebonnet’s communities today.

— Kirsten Tyler contributed to this story

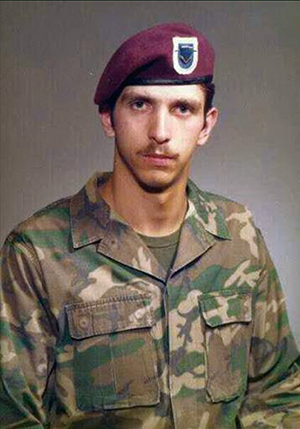

David Simmons

U.S. Army Specialist 1978-1982

Doretta Simmons

U.S. Army Captain 1983-1991

David and Doretta Simmons each had distinguished, demanding and fascinating Army careers — but they didn’t meet until after their military service.

Married since 2019, they now live on family land in the small community of Lincoln in Lee County. They are active members of the nearby American Legion post in Giddings and give back to veterans every chance they get. Their military service, at different times and in different places, gave them shared experiences and mutual goals that shaped their life together.

DAVID SIMMONS

David’s is the classic soldier’s story: A young man from small-town America, steeped in love of country and a sense of duty, pushes himself to become a paratrooper in the Army’s storied 82nd Airborne Division.

As a kid in Granite City, Ill., David was a junior firefighter and a fan of John Wayne movies. “Growing up in a small and poor town, I knew that the opportunities for success after high school were limited,” he said.

He graduated from high school early and celebrated his 18th birthday in winter’s icy grip during boot camp at Fort Knox, Ky.

He wanted to excel and was willing to work hard. That led him to become a paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne Division, also known as the All Americans, based at Fort Bragg, N.C. The division is renowned for its rapid deployment capabilities, airborne assaults, historic battles and role as the military’s Global Response Force.

Among David’s most vivid memories are the tense days after the start of the 1979 Iran hostage crisis, a 444-day ordeal when 52 Americans were held captive at the American Embassy in Tehran. “Just before President Ronald Reagan’s inauguration in January 1981, we suited up with parachutes and full equipment and were sitting on the runway at Pope Air Force Base, ready to go to Iran,” he said. “I was thinking that this was really it. We are going.”

Suddenly, the mission was called off. Iran had released the hostages during Reagan’s inaugural address.

Even without seeing battle, life in the 82nd Airborne was grueling with constant field duty and on-call status. Expectations were high, and the pace was relentless. “We always had to work at a high level. Your normal vacation leaves and regular weekends off were a fleeting notion,” David said.

Airborne jumps were his most memorable experiences. “The airplane doors would swing open, the wind would be screaming, and the jumpmaster would yell, ‘Hook up!’ ” David said. In that moment, just before they leap, every paratrooper on board finds something to believe in, he said.

The Army forged David into a deliberate man. “I know that I am a tougher, more resilient, disciplined and respectful person due to my time in service,” he said.

DORETTA SIMMONS

“Even as a teenager, I never had a doubt that one day I would enlist in the military,” Doretta said.

Inspired by her father, James Williamson, a chief master sergeant who served 34 years in the Air Force, and her mother, Patsy, who encouraged her ambition, Doretta’s path was one of purpose and passion.

After graduating from Lexington High School in Lee County, Doretta enlisted in the U.S. Army Reserve for military intelligence reconnaissance. She completed basic training at Fort Jackson, S.C., and advanced training at Fort Huachuca, Ariz.

“My father proudly pinned the lieutenant bars on my uniform and gave me my first salute,” Doretta said. “It was one of the most memorable moments in my life.”

She went on to earn a second lieutenant’s commission and then held several leadership roles at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, where thousands of military and civilian workers research, develop and test materials and technology for battle. She led a “special reaction team,” a highly trained unit of military police officers called into high-risk situations.

“Challenges were a way of life in the military,” she said. As a young female officer in the 1980s, Doretta faced the responsibilities of both leading by example and caring for soldiers in her command. “I always did my utmost to ensure that their concerns were addressed, and my soldiers received the best treatment possible,” she said.

AFTER THE MILITARY

David and Doretta met in September of 2018. After their military discharges, they began careers in law enforcement — but on different paths.

David joined the Houston Police Department Academy in 1982 at 21 and retired 40 years later as a lieutenant. Doretta left the Army as a captain at 37 and landed a job she’d always dreamed of: FBI special agent. She began her FBI career in 1983, working in Bryan and Houston.

After the 9/11 attacks, Doretta helped establish Bryan’s Joint Terrorism Task Force. She later became a squad supervisor in Houston and a member of the FBI’s Joint Terrorism Task Force. She retired after 32 years, in 2022. David retired the same year.

“I met the love of my life while on the job,” Doretta said. “All I can say is the man upstairs is watching over me, and I thank him every day for bringing David into my life.”

The Simmonses moved to Lincoln, the area where Doretta grew up, in 2024. “We live in her old stomping ground,” David said. He returned to law enforcement work this year as chief deputy in Burleson County’s Sheriff’s Office.

Their respect for fellow service members led them to the Giddings American Legion York Post 276, where they volunteer at events, attend meetings and provide transportation for other veterans.

“Our local chapter is comprised of a wonderful group of characters,” David said.

Veterans Day holds special meaning for the couple. “It’s a day for all who have served to be proud of themselves and proud of others who served,” Doretta said.

***

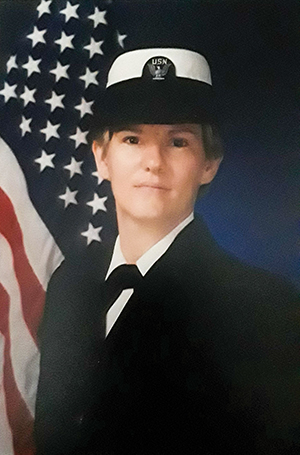

Orlanda Valka

U.S. Navy Chief Petty Officer 1989-2009

At 70, Orlanda Valka still carries the energy and determination that propelled her through two decades of military service.

She joined the Navy at 34, after working in Victoria as a payroll supervisor for a nursing home operator. Her father, a World War II Army veteran, inspired her to join the Navy. “I asked my parents for permission before enlisting,” she said. “I respected their blessing.”

She wanted to provide a better life for herself and her children. “I wanted to be an inspiration to other women, too,” she said.

Valka’s first stop was boot camp in Orlando, Fla. “I was an older lady joining, but I was a bodybuilder before I came in, so I was outdoing all the 18-, 19- and 20-year-olds.”

She trained for six months to be an aviation electrician before being stationed in Maine with a patrol squadron at the time of the Gulf War in the Middle East. Her first overseas deployment was to the naval air base in Sicily, Italy, during 1991’s Desert Storm military operation.

At first, though, Valka was assigned to work at a snack bar nicknamed “The Gedunk” for the sound coins made in its vending machines.

“I saw all these young service members working 12-hour days who didn’t have time to go to the galley to eat,” she said.

“So I started making food for them by cooking on hot plates.” That kindness earned her a commendation from the fleet admiral.

After six months, Valka began doing the work she was trained for: repairing aircraft electrical systems, starting with P-3 Orion reconnaissance and surveillance airplanes. She kept moving — to Jacksonville, Fla., to work with an aircraft training squadron, then to Norfolk, Va., to work on Sea Dragon mine-hunting helicopters.

In the middle of that, Valka changed her career path to become a Navy career counselor, helping guide others’ futures in the Navy and beyond. She was the first career counselor at the Naval Technical Training Unit in Biloxi, Miss.

“I helped everyone in the command get orders, change career directions, plan re-enlistments and retirements. I even organized retirement ceremonies,” she said.

Her first duty station as a career counselor was on the storied USS Enterprise aircraft carrier, a prominent setting for “Top Gun,” the 1986 movie that was another inspiration for Valka to join the Navy.

She was the first female petty officer to join the ship’s ranks and the first woman to earn the wings of an aviation warfare specialist, she said.

Valka retired from the Navy at 54 with 20 years of service. Today she lives in Bastrop, staying active as a volunteer for the city’s visitor center and the Chamber of Commerce.

The Navy is still close to her heart. “If I could go back out to sea, I would do it in a heartbeat,’’ Valka said.

***

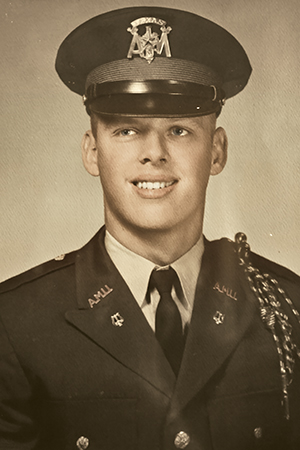

George House

U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel 1973-1998

As a child, George House was a member of 4-H. That’s when he first learned the importance of responsibility and character. Throughout school, then in the military and even now, he lives by the motto of that youth development organization: “To make the best better.”

House graduated from New Braunfels High School in 1968, then attended Texas A&M University, where he majored in business management. He was a member of the Fightin’ Texas Aggie Band and Corps of Cadets.

Between his junior and senior years at A&M, House completed Army basic training at Fort Riley, Kan. “The training breaks you down as a person, emotionally and physically,” House said. “But it built me right back up along with the rest of those at boot camp.”

The A&M Corps gave him many opportunities: eight semesters of military science courses, completion of boot camp and, on his 22nd birthday, a commission as an Army second lieutenant. In 1973, House attended Officer Basic School in Fort Knox, Ky., then started in the 2nd Armored Division at Fort Hood. There, he was an armor platoon leader, guiding 45 men through training exercises with battle tanks. He remained at Fort Hood for about 12 years, doing operations planning and coordinating services and supplies.

His first deployment was to Panama as a major in civil affairs in 1989. For more than five months, he helped civilians move to safety away from battles between the U.S. military and fighters led by the country's military ruler, Manuel Noriega.

A year later, House returned to the U.S. on reserve. He married Stephanie Rainosek in 1993, and the couple moved to Lockhart. House did contingency training until he was deployed to Bosnia in southeast Europe in 1994, a year before the end of the war that began there after the breakup of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s.

House, then a lieutenant colonel, worked with NATO as both an agriculture officer and the point of contact for about 20 nations that had sent troops to the area. Their focus was to keep fighting forces apart and to improve the country's agriculture practices. While there, House developed a curriculum for two Bosnian universities to improve agriculture programs.

He also helped overturn an antiquated law that required veterinarians to artificially inseminate cattle rather than allow ranchers to grow their herds through natural conception.

After six months in Bosnia, House retired in 1998 with 25 years of service in the Army. He returned to Texas at age 48.

House and his wife continue to live in Lockhart. Since retiring from the military, he enjoys remodeling antique cars and has become a member of the Lockhart Volunteer Fire Department and American Legion Post 41.

“We are commanded to serve others,” he said. “Community service is important, and you have to serve before you can lead.” Although his service looks different now than it did in the military, he still finds value in being part of something bigger than himself.

***

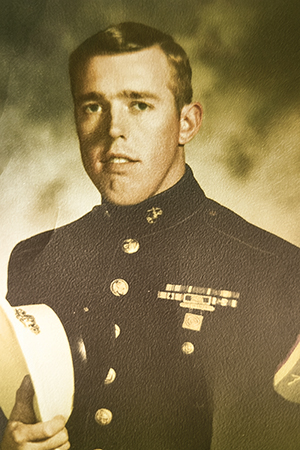

Davie Coker

U.S. Marine Lance Corporal 1968-1971

Davie Coker doesn’t seek attention or accolades. At 76, he speaks with soft conviction. When he shares his story, it’s with the weight of experience and the humility of someone who has seen the best and worst of humanity.

Born and raised in Roby, a community about two hours southeast of Lubbock, Coker enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps in 1968 at 19. Initially assigned to work as a military electrician with the 5th Marine Division at Camp Pendleton, Calif., Coker quickly requested a change. “I went to my sergeants and said, ‘I joined the Marine Corps to go to Vietnam,’” he said. That determination led Coker to work in motor transportation, which would place him on the front lines.

After completing rigorous training in guerrilla warfare and jungle survival, Coker was deployed with Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, to Vietnam in early 1970. “When we landed in Da Nang, the flight we were on never shut off the engines,” Coker said. “They just told us to get out here, get off the plane.” It was a stark and sudden introduction to war.

His training suggested he would drive and maintain vehicles, but Coker’s primary role became that of a Marine rifleman.

He conducted convoy missions, constructed defensive positions and worked alongside K-9 units trained in detection of both enemy troops and explosives in the jungles northwest of Da Nang. The work was dangerous, but camaraderie and humor helped the Marines endure.

“Vietnam — it was full of tragedy. You just dealt with it, you know?” Coker said.

During his time in Vietnam, he worked with Civil Affairs for about six months with villagers during the night, helping them set up perimeters to protect themselves. He also worked with Delta Company to get K-9 units into operation in the hills.

Coker’s more than 10 months in Vietnam left physical and emotional scars. He was unknowingly exposed to white phosphorus, a chemical used in artillery shells that ignites when exposed to oxygen. He gradually lost vision in his right eye. Despite multiple surgeries, the damage was irreversible. “You don’t always know what’s happening to you in the moment,” Coker said. “But you carry it with you.”

He recalled the intensity of his time in Vietnam — where survival often depended on instinct, quick decisions and the strength of his fellow Marines, he said.

Coker returned to Texas in February 1971 and installed irrigation systems for farms near Lubbock. Later he worked in electrical and mechanical maintenance, and moved to Kansas. “When we got back from the war, service members would sit inside the VFW in Lawrence, Kansas, maybe order a pitcher of beer and talk about our time there. But only the funny stuff. We made a rule: no talking about the bad stuff, just the moments that made us laugh.”

Coker remained steadfast in his commitment to service. He settled in the Tahitian Village area of Bastrop in 2007 and became an active member of American Legion Post 533, holding several leadership roles there. “You can’t slow down,” Coker said. “That’s when you fall.”

The American Legion gives Coker a way to help veterans stay connected, supported and understood. “It’s about being there for each other,” he said. “We’ve all been through something, and we understand in a way that others might not.”

Coker doesn’t dwell on the past, but he does honor it. He moves forward and supports those walking a similar path.

Fifty-five years after he served in Vietnam, Coker holds fast to his belief in America’s military. “I served because I believed in something bigger than myself,” he said. “And I’d do it again.”

***

Don Holley

U.S. Air Force Captain 1970-1980

Don Holley was only 22 when he left Alabama to chase a dream that would take him higher and faster than most people would ever dare. “I wanted to fly fast things,” Holley said, recalling the moment he chose the U.S. Air Force over a family legacy rooted in the Army.

His father and three uncles, all World War II veterans, had secured him an appointment to the Army’s prestigious West Point military academy — without telling Holley. When he chose not to accept their offer, Holley had to pay for college on his own.

By the time Holley had earned a degree in aerospace engineering at Auburn University, his father had softened — so much so that he and an uncle pinned the lieutenant bars on Holley’s uniform at graduation, when Holley was commissioned into the Air Force.

Holley began his decade-long career in the Air Force in 1970. He flew combat missions in Southeast Asia and test flights that pushed the limits of aviation. He served a little over a year at Takhli Royal Thai Air Force Base, flying missions over Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. “In combat, you do things you would not normally do,” he said. “And you experience things you’re never going to experience anywhere else.”

His most harrowing experience came in 1977, he said, during a test flight of an F-111 fighter-bomber over the Pacific Ocean. Tasked with pushing the aircraft to Mach 2.5, he reached Mach 2.42 when both engines exploded. “A fireball engulfed the canopy,” he said. His flight test engineer reached for the ejection handle, but Holley grabbed his hand and the handle, stopping him.

“If you go out at Mach 2, you’re not going to make it,” Holley told him.

Instead, Holley pulled the aircraft into a steep climb, up past 70,000 feet — high enough that a lack of oxygen extinguished the fire. He managed to restart one engine and brought the damaged aircraft back to McClellan Air Force Base in Sacramento. “I saved a $17 million airplane, but I still got my butt chewed,” he said.

Holley was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross — one of the military’s highest honors for heroism or extraordinary achievement during flight — plus a Service Medal and four Air Medals.

After 10 years of service, he left the Air Force. He married his wife, Lois, two weeks after his last test flight.

Five months after leaving the Air Force, he started work for Schlumberger, the global oil and gas service and technology provider, in Brenham. He founded Holley Oil Co. in 1989. His firm drilled more than 30 successful wells in Texas before he retired in 2014.

Today, Holley is 77. He still lives in Brenham, staying active with the Washington County Veterans Association and Brenham VFW Post 7104. He honors the legacy of fellow airmen by helping maintain the F-111 aircraft memorial in Brenham — a tribute to 10 crew members lost during Operation Linebacker II in 1972 over Vietnam. Holley knew some of the men memorialized.

Holley has advice for veterans who struggle with their past: “God has a way of getting us through everything,” he said. “He won’t ever give you more than you can handle.”