The cooperative way

Recent news

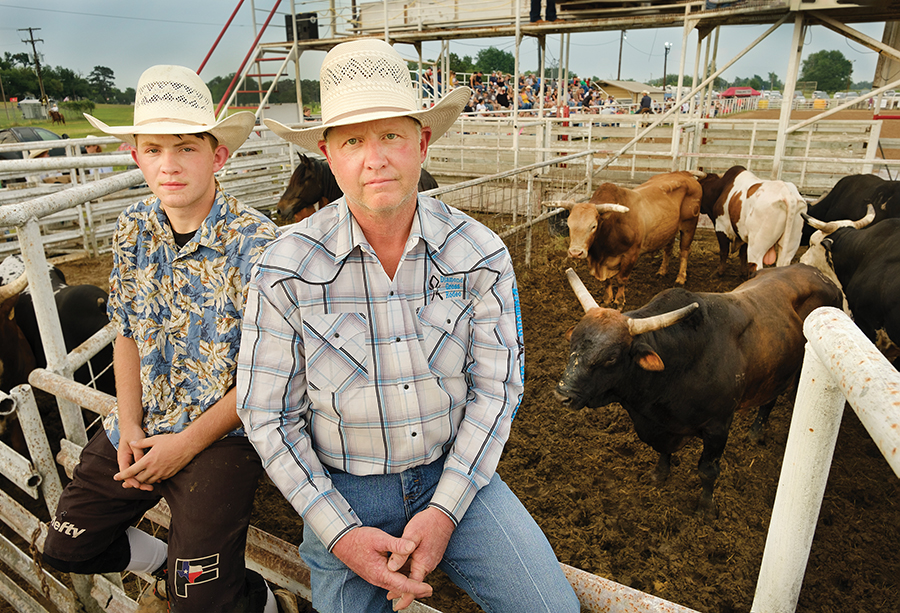

Today’s bullfighters skip the face paint and silly clothes for the serious business of protecting riders in the rodeo ring

Story by Pam LeBlanc -- Photos by Laura Skelding

If a snot-slinging, 1,500-pound hunk of muscle and rage hurtled across an arena in your direction, would you run toward it or beat a hasty escape?

Your answer could determine whether you’d make a good bullfighter, the term now used in the U.S. and Canada to describe the rodeo athletes who distract bulls and protect riders during bull-riding competitions.

They used to be called rodeo clowns, but there’s not much that’s funny about working under such dangerous circumstances.

“The Secret Service protects the president. We’re there to take the bullet instead of the cowboy,” said Wesley McManus, a former bullfighter who now owns Diamond Cross Rodeo Company, a Lexington-based contractor that provides bucking horses for rodeos across Texas. “In the moment, you just go in there and step in between the cowboy and the bull.”

McManus, 50, spent 20 years tangling with the angry Volkswagen Beetle-sized beasts.

“It’s like jumping out of a plane,” he said. “A lot of people don’t see the reason for it. But there’s that rush, that feeling- — there’s nothing like it. It starts a fire inside you, and then it turns into a passion for the sport of rodeo and the whole Western way of life.”

Learning the ropes of bullfighting

McManus grew up in Lexington in Lee County and did some bull riding in high school. He eventually decided he was better at helping cowboys get away from snorting bulls than trying to ride them. Plus, the paycheck was steadier: Bullfighters typically earn between $200 and $2,000 per show, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. He started learning when he was just 18.

“I told my mom and dad when I was 5 that I wanted to go to rodeo clown school. They thought it was cute until 12 years later when I was still saying it,” McManus says.

Some who do the job still wear greasepaint and bright clothes, but many don't. Instead, they wear technical jerseys and often belong to the International Professional Rodeo Association.

Skills essential to the job are “reading cattle and anticipating where the rider is going to come off,” McManus said.

McManus got his start as a bullfighter at a small Sunday afternoon rodeo in Lexington and eventually worked his way into bigger gigs. Mark Goodson, now chairman of the Lee County Sheriff’s Posse Rodeo, gave McManus his first big bullfighting job at a Youth Rodeo Association event at the arena in Giddings.

“You see the ‘want to’ in guys like Wesley,” Goodson said. “He was a natural.”

Some people enroll in bullfighting training classes, such as those offered around the country by famed bullfighter Cody Webster, who this year offered classes in San Antonio, Fort Worth, Cleburne and Arlington. Webster is considered one of the greatest bullfighters of this generation. Clinics are also offered in New Caney, near Houston. Others just practice skills on their own or at places like Bad Dog Rodeo in Belton, which offers a practice pen for up-and-coming bullfighters.

McManus is mostly self-taught.

He started by sorting calves and paying attention to which hoof an animal leads with while running. That “lead” telegraphs which direction the bull is likely to pivot, tipping off bullfighters which direction to move.

“A lot of it is natural reaction,” McManus said. “You can’t teach anybody how to be cattle savvy, and you can’t teach heart, but you can sharpen skills.”

Typically, two or three bullfighters and one barrel man (the athlete who hops into a padded barrel at which an angry bull charges) position themselves on either side of the bull when it bursts out of the chute and into the arena.

The rider has to stay on the bull for at least 8 seconds to earn points. They sometimes get a hand caught in the rope they hold to stay in the saddle. When that happens, the bullfighter works the rider’s hand loose, then draws the animal away from the rider when he finally lands on the ground.

“When that rider gets hung up, they’re depending on you to get them out of a jam,” said Goodson, the rodeo chairman. “You’re going to get hit and hurt. It’s a matter of how bad.”

And it can get bad.

“When you get run over, you’ve got four feet coming at you. You’ve got to worry about getting back up, because he’s probably coming back for you,” McManus said.

McManus recites a list of injuries he has suffered during his career: a blown-out knee, broken ankle, cracked ribs, dislocated fingers and plenty of stitches.

One memorable day, a rampaging bull stepped on his face and broke his teeth. After that, he said he prayed: “If I’m not supposed to do this, take the want away.” But the desire to be a bullfighter didn’t fade. “When I came back, I was on fire,” he said.

Eventually McManus retired, shifting his focus to the business of providing livestock to rodeos.

Like father, like son

A generation later, McManus’ son is following in his father’s footsteps. Like his dad, Dylan McManus knew early on he wanted to become a bullfighter.

“We tried to keep him away from it as long as we could,” Wesley McManus said.

The fear he now feels as a parent watching his son in the ring far exceeds the fear he endured in the arena while facing a bull, he said.

“I love it when young guys come in, but you’ve got to be really serious,” Wesley McManus said. “You can get hurt. We’ve lost a few. If you’re out here for the girls, you’re in it for the wrong reason.”

Dylan, 18, started bullfighting almost three years ago.

“My dad was really good when he did it and I looked up to him and his buddies as role models,” Dylan said. “I guess it’s always been in my heart to do it.”

He started at age 9, working with his father to sort calves in pens at his home. “We’d go to the sale barn and buy something little that was pretty mean,” he said. “I would learn the fundamentals with something that wasn’t big enough to hurt me too bad.”

That evolved into bullfighting at small events, which led to working at larger events like the Cowboys Professional Rodeo Association Finals in Angleton, near the Texas Gulf Coast, and the San Antonio High School scholarship finals at the San Antonio Stock Show & Rodeo.

Now Dylan wants to make a career of it.

“There’s nothing like making a good (cowboy) save and they get up and shake your hand and they say thank you,” he said. “There’s nothing like knowing you’ve got somebody’s back.”

The hard part is pushing fear aside. “You’ve got to take control over your mind and not be afraid of what’s going to happen,” he said. “It’s really hard to make yourself go up to a big animal that’s trying to hurt you.”

When done right, though, it’s a rush like no other.

“You’ve got to have three (extra) sets of eyes. You’ve got to know when (the cowboy’s) going to fall, where the bull’s going to go, where your partner’s going to go and where you’re going to go,” he says. “That’s a lot of timing and calculation, and it happens so fast. It’s basically fight or flight.”

That’s why a good partner matters, and for Dylan McManus, that person is Dakotah Teague. The two team up often, and worked the Cowboys Professional Rodeo Association Finals this summer, where both bullfighters got up close with thrashing animals. McManus had to grab a bull’s head to distract it from a bullrider, and Teague took a couple of hits. He described the experience as similar to what it might feel like standing in front of a car going 15 mph.

“It helps a lot more when you trust someone on the other side of the bull to save not only the bull rider, but yourself if you get down. It’s a brotherhood, that’s what it is,” said Teague, 31, who started bullfighting when he was in high school.

Teague honed his skills at a bullfighting clinic with well-known bullfighter Cody Webster, then started working rodeos a decade ago.

Because injuries are common, the bullfighters wear vests plated with thick plastic that can make an errant hoof slide off and help distribute the impact of a kick over a wider area. They also wear knee and ankle braces. Dylan McManus doesn’t wear a helmet — “Just my old black felt cowboy hat” — but he does lace up basketball shoes before he heads to the arena.

“It’s hard to run in boots,” he said.

The camaraderie and connection among athletes keeps them coming back. It’s a family, they say.

“Oh, we love the sport,” Teague said. “We love what it’s all about and we love protecting cowboys. We always say we want the cowboys to go home safe to their families before we do.”

Want to watch the bullfighters?

Catch all major rodeo action across the Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative service area in 2024.

RODEO AUSTIN

March 8-23

Rodeo Austin Fairgrounds, 9100 Decker Lake Road, Austin

rodeoaustin.com

email: info@RodeoAustin.com

FAYETTE COUNTY SHERIFF’S POSSE RAM RODEO

April 19-20

Fayette County Sheriff's Posse Arena, 2141 Blankenburg Lane, La Grange

Fayette County Sheriff’s Posse Facebook page

email: fcasnpowell@verizon.net

LEE COUNTY SHERIFF’S POSSE RODEO

April 18-20

Lee County Sheriff's Posse Arena, 2591 U.S. 290, Giddings

lcspgiddings.com

email: lcspgiddings@gmail.com

CHISHOLM TRAIL ROUNDUP RODEO

June 12-15

Lockhart City Park, 504 E. City Park Road, Lockhart

lockhartchamber.com/chisholm-trail-roundup

email: staff@lockhartchamber.com

BASTROP HOMECOMING & RODEO

July 30-August 3

Mayfest Hill Park, 25 American Legion Drive, Bastrop

bastrophomecomingrodeo.org

email: generalinfo.bhr@gmail.com

WASHINGTON COUNTY FAIR RODEO

Sept. 10-23

Washington County Fairgrounds, 1305 E. Blue Bell Road, Brenham

washingtoncofair.com

email: dean@washingtoncofair.com

COLORADO COUNTY FAIR & RODEO

Sept. 12-14

Colorado County Fairgrounds, 1146 Crossroads Blvd., Columbus

coloradocountyfair.org

email: info@coloradocountyfair.org

AUSTIN COUNTY FAIR & RODEO

Oct. 10-12

Austin County Fairgrounds, 1076 E. Hill St., Bellville

austincountyfair.com/prca-rodeo

email: ACfair@austincountyfair.com

GUADALUPE COUNTY FAIR & RODEO

Oct. 10-13

Guadalupe County Fairgrounds, 728 Midway, Seguin

gcfair.org

email: office@gcfair.org

ROCKDALE FAIR & RODEO

Oct. 18-20

Fair Park, 200 Walnut St., Rockdale

rockdalefairassociation.com; Rockdale Fair & Rodeo Facebook page and rockdaletx.gov/343/Rockdale-Fair-Rodeo

email: rdalefair@gmail.com

WILLIAMSON COUNTY FAIR AND RODEO

Oct. 23-26

Williamson County Expo Center, 5350 Bill Pickett Trail, Taylor

wilcofair.com/events

email: info@wilcofair.com

Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative and LCRA representatives present a $25,000 grant to the Maxwell Community Volunteer Fire Department for new rescue gear. The grant is part of LCRA’s Community Development Partnership Program. Pictured, from left to right, are, Ambrose Garcia, firefighter; Rick Arnic, LCRA regional affairs representative; Alfredo Hernandez, firefighter; David Childress, fire chief; Margaret D. “Meg” Voelter, LCRA board member; Milton Shaw, Bluebonnet Board member; Mark Kirk, VFD operations manager and firefighter; Jo Anna Gilland, Bluebonnet Lockhart-area community representative; and Hank Alex, Caldwell County deputy chief of emergency management.

The Maxwell Community Volunteer Fire Department will purchase new rescue gear to help keep firefighters safer while responding to emergencies, thanks to a $25,000 grant from the Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative and Lower Colorado River Authority.

The Community Development Partnership Program grant, along with $8,230 in matching funds from the department, will pay for 10 new sets of bunker gear, with each set including a jacket, pair of pants and suspenders.

“Our current gear is nearing expiration and is almost out of service,” Fire Chief David Childress said. “It’s important that we update our gear to keep our first responders safe.”

The gear provides protection against smoke, heat, water, steam and direct flames and is worn when responding to structure fires, car fires and other emergencies. Bunker gear is custom fitted to the person wearing it, so most of the firefighters in the department will receive a new set of gear.

“Using newer gear builds confidence in our firefighters because they feel a little safer as they enter structures,” Childress said. “When you enter a structure fire with older gear, you get second thoughts.”

He said having newer gear will give firefighters peace of mind as they work to protect the public.

“Our community is growing rapidly, so we need better gear to keep up with the growth and keep people safe,” Childress said. “With this gear, we will be better equipped to preserve lives, properties and structures.”

Maxwell Community VFD serves the community of Maxwell and provides emergency services to Caldwell County Emergency Services District #2. It also provides mutual aid to surrounding counties and districts.

The community grant is one of five grants being awarded by Bluebonnet and LCRA through LCRA’s Community Development Partnership Program, which helps volunteer fire departments, local governments, emergency responders and nonprofit organizations fund capital improvement projects in LCRA’s wholesale electric, water and transmission service areas. The program is part of LCRA’s effort to give back to the communities it serves. Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative is one of LCRA’s wholesale electric customers and is a partner in the grant program.

Applications for the next round of grants will be accepted in January. More information is available here.