The cooperative way

Recent news

Stories by Melissa Segrest

Photos by Sarah Beal

The first time, they signed up for their country. The second time, they signed up for their community. Both times, they signed up for something bigger than themselves.

Nineteen employees of Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative are U.S. military veterans. They were in the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marines. They went when and where our country needed them – from 1966 to 2018, from Vietnam to Virginia, California to Afghanistan. They gave up family time, the comforts of home and the lifestyle most of us take for granted.

Now, their duty station is a 24/7 workplace that provides another essential service: providing safe, reliable electricity to more than more than 114,000 meters in 14 Central Texas counties.

Both jobs honor duty and responsibility. They work to protect many people they may never meet. Each employee is one on a team of many, and the team is the way the job gets done.

That’s double duty to serve the masses. But duty, it seems, is their destiny.

- Denise Gamino

Taylor Rutledge

Taylor Rutledge holds the American flag that flew in the back of his medevac unit’s Black Hawk helicopter in Afghanistan.

A winding, remarkable path brought 28-year-old journeyman line worker Taylor Rutledge to Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative.

He grew up in Hooks, a small town 15 miles west of Texarkana. At 19, he quit his job on a cattle ranch and headed for an Army recruiter’s office. “I told him I wanted to be some kind of mechanic,” he said. His twin brother was already in Air Force basic training and his parents agreed with his decision.

U.S. ARMY, SERGEANT

2012-2015

K-16 Army airfield, Seoul, South Korea;

Fort Bragg, N.C.; Jalalabad, Afghanistan

- Bluebonnet employee for 3 years

- Journeyman line worker

- Lives in Bastrop

He went to Fort Jackson, S.C., for basic training, then to Fort Eustis, Va., for advanced training for helicopter mechanics. “They told me I could either do Chinooks, the big helicopters, or Black Hawks. I didn’t know about either one, so I said, ‘Give me Black Hawk.'"

He got what he asked for and was off to K-16 Army airfield in Seoul, South Korea, to do aircraft maintenance in an air assault company and train with Korean troops. “The city was huge. It was a culture shock,” he said. Buddies finally tempted him off base, where he learned to use the subway and enjoy the food. “It was spicy, but I liked it.”

He was in Seoul for a year.

Fast forward: He fell in love with a family friend’s daughter, Samantha Diles, over Facebook chats from Korea, met her at the airport after landing from overseas, put in six months at Fort Bragg, N.C., before coming home to New Boston, Texas, in December 2013. They married and moved to North Carolina.

He knew something was coming. “We flew from Fort Bragg to El Paso and did high altitude training in the mountains of New Mexico, to adjust to low oxygen levels,” he said. A few months later, in July 2014, Rutledge was deployed to Afghanistan as a member of an airborne medical evacuation unit. He was 21.

“I was fortunate. The medevac mission is pretty special,” he said. His platoon went to Jalalabad in far eastern Afghanistan, a city flanked by mountains that dwarfed those of New Mexico.

His first mission was a nighttime ‘hoist extraction.’ A soldier had fallen down a cliff and had a concussion. “It’s the hardest mission,” Rutledge said, involving strapping an injured soldier to a “Sked” stretcher and hoisting him to a hovering helicopter. They were able to land the helicopter and return the soldier to base. “I wasn’t scared but it was a little nervewracking. But you train so much it just becomes second nature.”

In Afghanistan, Rutledge saw injuries, mass casualties and combat deaths. Once, an enemy explosive on a motorcycle blew up a seven-truck Army convoy. “One truck, one of the biggest in the Army, had 14 people in it,” he said. “When we got there we couldn’t even tell what kind of truck it was. It was a big ball of fire and metal. Two people were trapped inside. Everybody lived, but there were a lot of injuries.”

After his nine-month stint in a war zone, Rutledge felt a sense of accomplishment. “All of the training was for that. It was put to use,” he said. “Being an aircraft mechanic, you don’t expect to do CPR or start an IV in a helicopter. It’s a good feeling to know you did well in a horrible situation.”

He finished active duty and joined his wife and daughter near Fort Worth. “I wanted to do something different, learn something new,” he said. Rutledge attended line worker college in Denton and was hired by Bluebonnet in April 2018. He has been at the cooperative for 3½ years. He and his wife have two children, 5-year old daughter Laney and little Tate, born Sept. 16, 2021.

“I wanted to find a career that was bigger than just myself, more than just going to work and going home,” he said. “Line work was an opportunity for me to do that and make a good living.” Now he works out of Bastrop, making service calls and restoring power.

Line work can be stressful, but just like in the military, there is a lot of training at Bluebonnet. Rutledge isn’t easily ruffled by schedule changes and outages.

The Army tries to create leaders, and Rutledge still carries that mission. “I won’t ask my crew to do anything I wouldn’t do,” he said. “I wouldn’t ask them to walk through knee-deep water during a nighttime storm to restore power alone. No, we’ll go walk out there together.”

Matthew McGarr

Since enlisting in the Navy at 18, Matthew McGarr has been working with computers and technology. “I was a computer geek with a clearance,” he said. “In some ways, it’s similar to what I’m doing now as a control center operator at Bluebonnet.”

McGarr grew up in the Texas Panhandle and wasn’t ready for college after high school. But the military made sense: His grandfather was in the Army in World War II, and his father flew Army helicopters in Vietnam.

U.S. NAVY, PETTY OFFICER SECOND CLASS

1988-1994

London, England; Norfolk, Va.

- Bluebonnet employee for 14 years

- Control center operator

- Lives in College Station

He reported for boot camp in San Diego in 1988, and, after an additional round of training, he was stationed in London for three years.

It wasn’t the typical military experience. McGarr worked in the heart of the city but was not allowed to wear his uniform, because “the queen had tired of seeing uniforms in World War Two,” he was told. Conservative banker attire helped him blend in, “except, when you opened your mouth everybody knew you weren’t from there,” he said.

McGarr was allowed to soak up London sites, sports and food in off hours. He traveled around Europe and even tried to teach some Brits how to play softball, with limited success.

After London he went to Norfolk, Va. for the remainder of active duty on the USS George Washington aircraft carrier, helping install technology and outfit the ship to operate.

The massive carrier housed 6,000 military members, essentially a floating town. McGarr’s berth was just below the flight deck, so he learned to sleep through takeoffs and landings.

He completed active duty in 1994 and earned a bachelor’s degree in information and operations management from Texas A&M University. He came to Bluebonnet in 2007 to work in the 24-hour control center, mastering a steady flow of new technologies that monitor Bluebonnet’s electric system, power outages and line workers.

The military taught McGarr how to work with people who are under pressure and guide them through difficult situations, he said.

He has a short list of Navy takeaways: Take care of things early, before they become problems. What goes around, comes around. And, most important, “You are just a small part of everything. There’s something bigger than you in life,” McGarr said. “And you have to work as a team. Not everything can be done by you.”

Jorge Varillas

Before Google and YouTube made it easy to research the U.S. military, there was the legendary reputation of the Marines: tough, brave and unwavering from their mission. Jorge Varillas looked up to them and enlisted a few years after high school.

“I thought if I don’t try it now, I might regret it. I didn’t want to wonder what it might have been like 10, 20 years later,” he said. Varillas left his home in Nixon, Texas, and went through three months of boot camp at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot in San Diego, then another three months of specialized training at the School of Infantry there.

“I didn’t realize it was going to be such a mental challenge,” he said. “I thought it would be mostly physical.” The Marines demanded discipline, practice and precision. “The faster we got, the harder the drill instructors would get on us,” he said. “If one person would mess up, everybody would pay for it.”

U.S. MARINE CORPS, SERGEANT

1990-2000

Camp Pendleton, Calif.

- Bluebonnet employee for 26 years

- Engineering project coordinator

- Lives in Lockhart

Physical challenges were nonstop — miles and miles of running with a 60-pound backpack and a weapon. “The longest trek was mountain warfare training in Northern California,” Varillas said. It involved rappelling and crossing rivers using carabiners on ropes. “Then a blizzard hit. There was three feet of snow. Training was canceled and we hiked 20 miles back to camp.”

After California, Varillas returned to Texas and joined the Marine reserves at Camp Mabry in Austin. He trained for deployment to the Persian Gulf War in Iraq, which ended just before he was to leave. “I wanted to go,” he said.

Most of his military training was in California until 2000. He briefly joined a joint military-Drug Enforcement Administration task force to patrol the Sequoia National Forest in search of marijuana farms.

Varillas started out as a beginner at Bluebonnet, too. He began with a brush crew to clear vegetation in 1995 while still a Marine reservist, then moved on to be a Bluebonnet line worker. After several years, he designed plans for lines and equipment for locations getting new electric service. Now he is a project coordinator in engineering and has been at Bluebonnet for 26 years.

The next generation of the Varillas family – one of his four children – has enlisted. His oldest, 20-year-old daughter Aracely, joined the Air Force in April this year, and is stationed in Germany. “There’s a sense of pride in serving, I told her,” he said.

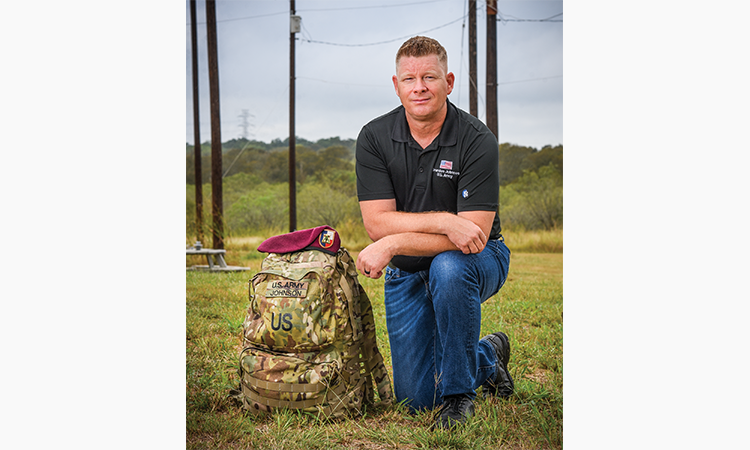

Brandon Johnson

Brandon Johnson was 17 when he and a buddy signed up for the Army. The next year, 1991, he started basic training and quickly learned that life at Fort Benning, Ga., was a far, hot cry from his frequently frozen hometown of Tolna in North Dakota.

He went on to advanced individual training at Fort Benning. “I got to do a lot of challenging stuff I never did before – and probably never will again,” he said. “Throw grenades. Shoot different caliber automatic weapons, anti-tank weapons. Learn how to set (remote-control) Claymore mines.”

Next was airborne school at Fort Benning, and Johnson found his military calling: jumping out of an airplane.

Learning to jump and land correctly are essential. Paratroopers hit the ground going about 18 feet per second. “Feet, knees, legs together – twist and crumple your body to the ground, end up on your back with feet on the ground,” Johnson explained. Those who walk off the landing zone without help after five airplane jumps have completed their training. U.S. ARMY, SPECIALIST

1991-1994

Fort Polk, La.; Fort Hood, Texas; Fort Benning, Ga.

ARMY NATIONAL GUARD, SERGEANT

2014-present

- Bluebonnet employee for 15 years

- Safety and training supervisor

- Lives in Bastrop

He was a mortarman at Fort Polk, La. with his regular duty unit, even after it was transferred to Fort Hood, Texas, and became part of the 2nd Armored Division. Specialist Johnson’s active duty ended in 1994.

If a military life didn’t pan out, he wanted to become a line worker. After learning the job and working in Texas and Colorado, he joined Bluebonnet in 2005. Now he is Bluebonnet’s safety and training supervisor.

His love for the jump never waned, and in 2014 he joined a National Guard unit in Mineral Wells, about 60 miles west of Fort Worth. He is a sergeant, going to drills several days out of most months. “I pack parachutes, various sizes of cargo chutes – we’ve dropped vehicles (from the air). And I still jump to stay current on requirements.

“It’s an adrenaline rush, that anticipation of going out the door. It’s more fun than coming down with the parachute open and seeing the view.”

His unit is activated after disasters, like when he prepared supplies to be dropped by parachute into hard hit areas after Hurricane Harvey in 2017.

Safety training and squad leadership are compatible, he said. “My style of teaching and communicating work in both roles,” he said.

John Horton

John Horton grew up in the small Texas town of Hamilton about 65 miles west of Waco and saw the Army as an opportunity to learn and grow. He began basic training in 1988, at 19, and was posted in South Carolina and Georgia before reaching his permanent station at Fort Hood in Texas.

He repaired radios used in Army helicopters — Hueys, Black Hawks, Apaches and Chinooks. Horton also worked on two-way radios used during weapons training.

U.S. ARMY, SPECIALIST

1988-1992

Fort Hood, Texas

- Bluebonnet employee for 1 year, 11 months

- Journeyman line worker

- Lives in Ledbetter

At Fort Hood he was part of the 6th Cavalry Brigade, Air Combat, then the 13th Support Command Corps.

Although the Gulf War began in 1990, Horton was not deployed. “I kind of wanted to go, kind of wasn’t sure,” he said. “But I was prepared.”

He recalled one day of loading equipment into trucks and traveling with a Fort Hood convoy to Houston, where their cargo would be shipped overseas. Much to his shock, one unfamiliar sergeant announced to him and his crew to finish up with their unloading, because “you’re going!” Despite the misdirected command to head for the Middle East, Horton and his crew returned to Fort Hood.

Horton admits he was “a bit of a mouthy kid” before the Army. But the discipline of the military helped him learn how to be an adult.

“I learned how to treat others with respect, and how to earn the respect of others. To be honest with yourself and others. To work hard, and do what you say you’re going to do,” he said. “You had to learn how to be a good hand.”

After 4½ years, Horton completed his Army stint in 1992. He worked at several electric cooperatives in Texas for years before coming to Bluebonnet in 2019.

“I feel proud that I served in the military, even though mine was mostly a peacetime Army experience. I would still be proud to serve in the military,” he said. “Your brother’s standing next to you, going through the same thing you are, and you are there for them. You had to be accountable, every day.”

That’s a lot like being a line worker, which can also be a life-or-death experience. He urges younger people in the field to take their jobs as seriously as he does.

And though Horton hasn’t worked on a military radio in a while, he doesn’t dismiss the idea. “I still might be able to,” he said.

Download this story as it appeared in the Texas Co-op Power magazine »

Story by Alyssa Dussetschleger

If you think you're seeing more electric vehicles on the roads of Central Texas, your eyes aren’t lying. By mid-June this year, more than 52,000 electric vehicles — or EVs — were registered in Texas, and 63% of them are model years 2020 or newer, according to data from the Texas Department of Motor Vehicles.

Of the 14 counties where Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative provides power, 10,329 electric vehicles were registered as of August, according to data from the Texas DMV. That’s a fraction of the cars and trucks registered in the area’s counties, but the electric vehicle numbers are going to grow.

One electric vehicle driver’s advice on avoiding ‘range anxiety’»

Teslas are the most popular electric vehicles in counties served by Bluebonnet: 5,179 are registered. Of those, slightly fewer than half are the popular Model 3 sedan, the most affordable Tesla at $39,000. There are another 1,848 Tesla Model Y mid-sized sport utility vehicles, which start at $53,990, on area roads. The least common Tesla (750 are registered) in the region is the high performing S model, a luxury sedan starting at $89,990.

Most popular after the Tesla models is Nissan’s Leaf, a compact car that starts at $27,400. There are 574 of them registered in the region. Next are Chevrolet Bolts, which start at $31,000, with 474 registered in our area.

Plenty of drivers nationwide — 71 percent — say they would consider buying an electric survey by Consumer Reports in 2020. Of course, the massive new Tesla manufacturing facility in eastern Travis County should have new vehicles rolling off the factory floor in a few months, which is certain to raise Central Texans’ Tesla-buying fever.

Two Tesla owners talk

Jeff Nelson was 55 when he bought his first vehicle, an electric Tesla Model 3, in 2018. He got his driver’s license just two years earlier.

The delay was tied to Nelson’s lifelong vision impairment, but that changed in 2015 when he got bioptic lenses, specialized vision-enhancing telescopic lenses that attach to eyeglass lenses. The bioptics can magnify what is seen up to six times, according to the private practice Bioptic Driving USA.

Even though he had his license, before 2018, Nelson didn’t need a car. He lived near his office in Austin and relied on public transportation or his wife to get around.

But three years ago Nelson and his wife, Taffy, moved into a new 2,500-square-foot home in the Whisper Valley subdivision in the Bluebonnet service area.

The development, on FM 973 just east of the Texas 130 toll road, has more than 200 single-family homes and 40 more are under construction. The houses all come with solar panels and other energy-saving options such as geothermal infrastructure, energy-smart appliances and prewiring for garage-mounted electric vehicle chargers.

Nelson did his homework and decided the Model 3 best fit his lifestyle and driving needs. He bought a Tesla wall connector to charge the car in his garage via a 220- volt plug (a standard household outlet is 120 volts) and a 45-inch tall lithium-ion battery to store electricity generated by his solar panels. The slim, rectangular 251-pound Powerwall, also made by Tesla, stores 13.5 kilowatt hours of power for use after the sun goes down or if backup power is needed. Nelson’s wall connector cost $500 and the Powerwall cost $7,500 in 2018.

With his car’s range of 300 miles on a full charge, and Nelson working mostly from home, he only charges his car once a week. His electric bill averages about $40 a month, he estimated.

Deanna Bodine is another Bluebonnet member who drives a 2018 Tesla Model 3.

She lives in Bastrop with her husband and five children, and has been a Bastrop County resident and Bluebonnet member since 2001. She teaches music at Emile Elementary School in Bastrop. Before buying the Tesla, she drove a 2011 Kia Sorento. She bought her Model 3 online, she said, and had it delivered to the Tesla service center on Research Boulevard in Austin.

When Bodine moved into her current home in 2019, she equipped her garage with a 240-volt outlet — the type commonly used for electric ovens, dryers or RV plugs — to charge her EV. She usually charges her car at home, daily. Her mobile charger, which came with her car, can charge 21 miles of range in an hour.

Charging her Tesla hasn’t made much of a noticeable impact on Bodine’s electric bill. “Maybe $20 to $30, but I couldn’t tell if it increased due to the heat or charging,” she said.

Bodine has been satisfied with her Tesla and would gladly purchase another electric vehicle. She’s not sure about the make and model, though. “The biggest factor will be nationwide charging ability,” she said.

Get ready for a wave of new electric vehicles

Electric vehicles are rolling past niche status and into the mainstream, and almost every major car manufacturer will offer an electric model in the next few years.

Among those on the list are Toyota, Ford, BMW, Audi, Volkswagen, Hyundai, Honda, Porsche, Kia, Stellantis (which includes Fiat, Chrysler, Jeep and Maserati vehicles), Volvo, Mazda, Mitsubishi, Jaguar, Subaru, Land Rover, Mercedes and General Motors.

As more EVs are made and battery technology gets better, their prices will likely compete with gasoline-fueled vehicles, accordingto the U.S. Department of Energy. Next year’s electric models range from the $29,990 MINI two-door, to the moderately priced $39,990 Kia Niro EV, all the way up to the $150,900 Porsche Taycan Turbo. Volvo has stated that by 2030, it would produce only electric vehicles. General Motors aims to offer 30 different EV models by 2025.

The first full-sized electric pickup from a major manufacturer, the Ford F-150 Lightning, is expected to hit showroom floors in mid-2022. The Lightning, which will start at $39,974 according to Ford’s website, looks similar to Ford’s other F-150 trucks. There are no Ford Lightnings in area showrooms as of this publication’s deadline, but you can reserve one online from your local dealership.

At its Bluebonnet service-area factory, Tesla and its CEO Elon Musk have said the company will make the newest Model 3 sedans, Model Y crossover SUVs and two new vehicles: the futuristic looking Cybertrucks, starting at $39,900, and the big Semi trucks for long-haul commercial drivers, starting at $180,000.

Manufacturers are touting many of the new EVs’ increased ranges (the distance an electric vehicle can drive on a single charge) and affordability. Nissan’s 2022 Ariya, an electric sport-utility vehicle, will retail for about $40,000, according to an estimate from Consumer Reports. The Ariya will have a range of 300 miles on a single charge if the buyer chooses the “long-range battery” option.

U.S. electric vehicle sales could account for 25% to 30% of the new-car market in 2030, and as much as 50% by 2035, according to projections by IHS Markit, a leading global data provider for major industries and markets.

However, EVs’ cost, range and battery longevity (which is typically 100,000 miles in standard electric vehicles today, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory) still make plenty of Central Texas drivers pause at the idea of going electric — especially those in rural areas who regularly travel long distances.

It will probably cost less to power an electric vehicle than a gasoline-powered car or truck. The U.S. Department of Energy says that fueling your car with gasoline costs nearly three times as much as fueling a vehicle with electricity. Additionally, the Alternative Fuels Data Center reports electric vehicles have fewer parts and usually do not need as much maintenance as gasoline-powered vehicles. The only maintenance required on Bodine’s Tesla has been “replacing the tires every three years or 40,000 miles, and windshield washer fluid as needed.”

A Chevrolet Bolt’s maintenance schedule includes tire rotation, air filter replacement and draining vehicle coolant circuits at 150,000 miles. Additional maintenance and care may include brakes, heat and radiator hose inspection, lights, windshields and wiper blades.

The most costly repair usually associated with owning an EV is the battery, according to Consumer Reports. The lifespan of an EV battery depends on the model. Chevrolet, for example, provides an eight year or 100,000-mile battery warranty. Tesla high-voltage batteries are under warranty for four years or 50,000 miles. Manufacturers typically do not publish pricing for replacement batteries, but if the battery does need to be replaced outside the warranty, it is expected to be a significant expense according to the Alternative Fuels Data Center.

A major factor in the rush to make electric vehicles in the U.S. is due, in part, to pressure and regulations from the federal and some state governments, according to Daniel Yergin, vice chairman of IHS Markit.

The drive for more electric vehicles faces significant challenges: Electric vehicle manufacturers will have to create entire new supply chains and the vehicles will require new charging infrastructure on a massive scale, he wrote recently.

The biggest challenge, however, will be changing car buyers’ habits: Moving from the familiar to the unknown on such a major investment won’t be easy. But as Texans see more EVs on the road and in the neighbor’s driveway, minds may change. Electric vehicles won’t rule the roads of Central Texas any time soon, but be prepared to make room.

New makes, models of EVs in 2022 and beyond

Automotive News, a weekly newspaper for the automotive industry, estimates that there will be nearly 100 models of electric vehicles available nationwide by the end of 2022. Buyers will see more crossover sport utility vehicles and pickups, from full to mid-size. Many new models will arrive in 2022, with preorders available now. Several automakers have also released plans for vehicles through 2024.

Chevrolet Bolt EUV

Starts at $33,000; Electric SUV, 2022 models in transit to dealers, available for purchase now; 247-mile estimated range; dual-level charge cord with attachment plugs for 120- or 240-volt outlets; hands-free and semi-autonomous driving assistance features; Level 2 charging outlet installed by Chevrolet at home of eligible buyers.

Kia EV6

Starts at $58,500; First edition of new Kia line of crossover EVs, limited number (1,500) being produced, coming January 2022; seats 5, futuristic design with dual curved screens and display, estimated 300- mile range; wait list available.

EVs coming in 2022 and beyond

- 2022 Tesla Cybertruck (manufactured in Travis County)

- 2022 Toyota bZ4X, Toyota’s first electric crossover SUV

- 2023 Subaru Solterra, Subaru’s first electric SUV

- 2023 Jeep Wrangler Magneto

- 2024 Ram 1500 EV, a full-size pickup

- 2024 GMC Hummer

- 2024 Honda Prologue SUV

- 2022 BMW and Mercedes Benz, releasing multiple EVs including small cars such as EQS from Mercedes Benz and SUVs such as the 2022 iX from BMW

Hyundai IONIQ 5

No pricing available; crossover, coming in 2022; estimated 300-mile range (168 kilowatt motor); equipped for “ultra-fast charging” of 60 miles range in 5 minutes; two years unlimited 30-minute free charging on some DC fast chargers in partnership with Electrify America.

Where to charge? Area EV stations

Looking for a place to plug in? PlugShare, a website and app that locates charging

stations, shows more than 30 electric vehicle charging stations in Bluebonnet’s

service area. They include:

Bastrop: Bring your own Level 2 charging cord and connector to Basin RV Resort, 98 Texas 71, 2 miles east of intersection with Texas 21; $10 per charging session.

Brenham: One Level 2 charging station with two charging cords at City Hall, 200 W. Vulcan St.; Level 2 charging stations at Coach Light Inn, 2242 S. Market St., free and open to public; chargers at Holiday Inn Express, 2685 Schulte Blvd. and at Best Western Inn, 1503 U.S. 290 E. for hotel guests’ use.

Caldwell: One Level 2 charging station at Bud Cross Ford, 150 Texas 36 at U.S. 21 intersection, free and open to public 8 a.m.-5 p.m., Monday-Friday; 9 a.m.-1 p.m. Saturday.

Cedar Creek: Four Level 2 chargers for resort guests at Hyatt Regency Lost Pines Resort and Spa, 575 Hyatt Lost Pines Road (off Texas 71 W.); chargers installed through partnership with Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative.

Elgin: Two Level 2 chargers at Austin Community College campus, 1501 U.S. 290, 2 miles west of intersection with U.S. 95; $4-$12 per charging session, based on time.

Giddings: 8 Tesla Superchargers at CEFCO Travel Center, 3025 W. Austin St. (which is also U.S. 290) 2 miles east of intersection with U.S. 77; payment required based on usage, charging time up to 30 minutes.

Manor: Two Level 2 Tesla chargers and 1 standard EV Level 2 charger (J-1772 connection) at Whisper Valley subdivision, 9400 Petrichor Blvd, at the Amenity and Discovery Center, free to the public; one Level 2 charger, free for residents of The Flats at Shadowglen apartment complex, 12500 Shadowglen Trace.

New Ulm: Two Level 2 chargers for visitors and the public at The Vine wedding and event venue, 25642 Bernard Road, 8 miles south of Industry.

San Marcos: 12 Tesla Superchargers at San Marcos Premium Outlets, 3939 S. I-35, payment required based on usage.

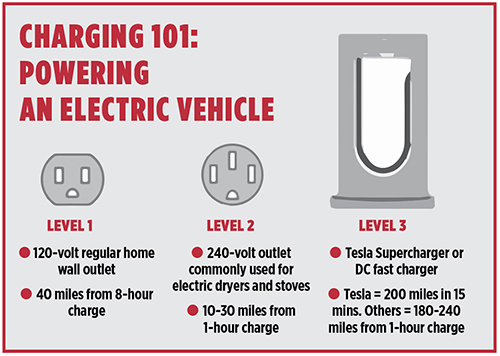

Charging 101: Powering an electric vehicle

Chargers vary in type, voltage, connector type, speed at which they charge and what vehicles they can charge. There are three levels of chargers: AC Level 1, AC Level 2 and DC Level 3 fast chargers (or Superchargers for Teslas).

There are three levels of chargers: AC Level 1, AC Level 2 and DC Level 3 fast chargers (or Superchargers for Teslas).

Level 1 is the simplest and slowest. A specialized adapter plugs the car into a standard 120-volt outlet. (Standard household outlets are 120 volts.) That will give the car about 3-5 miles of driving range per hour of charging — very slow.

Most EV owners use Level 2 AC chargers at home or on the road. The Level 2 runs off a 240-volt outlet, the same type used to power most clothes dryers. It can power an electric vehicle three to seven times faster than the Level 1 charger – about 10-30 miles of range every hour. A Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative member would pay $3.44 to give a 2021 Nissan Leaf enough power to drive 149 miles.

A new 240-volt outlet and wall charger should be installed by a certified electrician or installer.

If you’re looking for more juice, public charging stations are often equipped with powerful Level 3 chargers. A Tesla Supercharger, only for Teslas, can charge a Model 3 with 200 miles of range in 15 minutes. For most other electric vehicles, a Level 3 DC fast charger can provide 180 to 240 miles of range per hour of charging. Not every electric vehicle model can charge at Level 3, so check vehicle specifications.

Unless you drive a Tesla, there are two types of connectors for DC fast chargers, and they are not interchangeable between vehicle models. Make sure you know which type you have or need.

Public charging, especially Level 3, often isn’t free. Drivers may pay by the minute or by how much electricity they use. Prices can vary based on electricity cost and charging level.

Sources: epa.gov, energy.gov, Alternative Fuels Data Center (afdc.energy.gov), fueleconomy.gov, consumerreports.org, Kelley Blue Book (kbb.com), tesla.com, myev.com

There's an app for that (finding a charging station)

Most new electric vehicle models, including the Ford F-150 Lightning, Chevrolet Bolt EUV and Hyundai Kona, will have charging maps built into their navigation systems. But many electric vehicle owners opt for smartphone apps to help plan their routes, especially for longer trips.

PlugShare — Filter for your plug and charging level type, and exclude chargers currently in use; on its website, find amenities at charging stations such as restrooms

ChargePoint — Find stations, check charger availability, get updates about your vehicle’s charge status and range; at ChargePoint charging stations, app unlocks chargers for real-time charging updates; app also synchs with Apple and Google maps to find nearest available charger

ChargeHub EV Map — Trip planner will find charging locations on your route; create a user profile, check in to a station, leave comments and pictures to help other users select a station

Google Maps — Added EV charging stations to map features in 2011; search “charging stations” to find one nearby; see how many chargers are available, their type and power capabilities

Chargemap — Search a city or ZIP code using app or website to get charging station details, addresses and hours, amenities, charger types; apply filters to find correct power level and necessary connector; app also includes route-planning tool and user reviews of charging stations.

How do you buy a Tesla in Texas?

You cannot go to a dealer in Texas to buy a Tesla because Tesla doesn’t have dealerships in Texas — or anywhere else.

Texas law requires automotive manufacturers to sell their vehicles to independently owned third-party businesses such as dealerships, which then sell to individuals. One exception: used Teslas obtained through trade-ins can be sold by dealers.

Texans who want to buy a Tesla must either buy it online from tesla.com or in another state; then it must be delivered by Tesla to a regional Tesla service center for pick up. The vehicle will have out-of-state registration, and new owners have 30 days to register their Tesla in Texas, according to the Texas Department of Motor Vehicles.

Texas has 12 Tesla service centers. Those nearest the Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative region are in Austin (12845 Research Blvd. in North Austin), two in Houston (9633 Westheimer Road and 14820 North Freeway in North Houston) and in San Antonio (23011 I-10 W).

At tesla.com, you can buy new or used vehicles for an order fee ranging from $100 to $500. Buyers create a Tesla account and go through a step-by-step process of “delivery tasks,” which include submitting the final payment, financing and/or trade-in documentation. You’ll also receive the vehicle’s VIN and schedule delivery to a Tesla service center.

The waiting time for your Tesla varies with financing and model availability. The estimated delivery of new cars, at our time of publication, is January 2022 for a Model Y or Model 3, February 2022 for a Model S and April 2022 for a Model X. In early September 2021, there were many used car options on Tesla’s website.

Once your Tesla arrives at the service center, a technician will show you how to operate and navigate it. More information is at tesla.com/support/ordering.

Sources: statesman.com, capitol.texas.gov, businessinsider.com, tesla.com/support/ordering

Download this story as it appeared in the Texas Co-op Power magazine »