Scam alert: Members report increase in fraud attempts

Recent news

In area high schools, job and technical courses are growing alongside the demand for specially trained workers. Visits to classrooms at five Bluebonnet-area schools show the range of possibilities.

By Sidni Carruthers

Most weeks, teachers and staff at Del Valle High School can pick a day to skip the cafeteria burgers and dine at Cardinal Cafe.

On a recent school day, William Maldonado, a sophomore, started at 8:45 a.m. to cook chili for approximately 100 Cafe diners. He works with other students in the school’s spacious commercial kitchen, dining area and pastry kitchen, getting a feel for restaurant work by taking orders, waiting on tables and cleaning up after patrons leave.

The dining area is simple — no white tablecloths or fancy dishes. The freshly prepared meal, which staff and teachers pay for, includes an entrée, two sides, dessert and a drink. It’s a treat for the faculty and valuable training for students.

Maldonado is learning about the culinary and hospitality field. His training ranges from the industry’s history to the practical application of flavorings that bring out the best in a dish.

He is one of 470 students enrolled in Del Valle’s culinary arts and hospitality services program. Students who complete the coursework have internship opportunities at area businesses, including the Hyatt Lost Pines Resort and Spa, the Austin Convention Center and hospitality venues at the Circuit of the Americas. They can graduate with certification of their training credentials in restaurant management.

INTERESTED IN BLUEBONNET'S INTERNSHIP PROGRAM? »

If it has been a while since you went to high school — or you have a child or grandchild who isn’t there yet — you might be surprised at the breadth of career paths that fall under the “career and technical” umbrella at schools across the Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative service area. A high school student can train to become a dental hygienist, medical assistant, pharmaceutical tech, welder, construction manager, HVAC technician, home inspector, pipefitter or dozens of other careers without needing a four-year bachelor’s degree. Bluebonnet offers a four-year internship program in line worker training to area high school graduates. (See story, Page 20C)

In Texas, public high school students are required to take at least four college or career readiness courses, according to the Texas Education Agency website. More career and technical classes are being added at high schools, and, in the Bluebonnet region, more students are enrolling in the courses.

Career and technical jobs are abundant and they are the economic and employment mainstay of communities across the Bluebonnet region. Career and technical fields are expansive, essential and potentially lucrative. Trade industries are expected to grow 10% by 2028, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Area students can select from an ever-expanding variety of career and technical courses. Some offer certifications that can lead straight to a job. Other students plan to keep learning to get other certifications or an associate degree.

Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative actively supports area high school students and has been awarding scholarships for decades. In the last five years, the cooperative has given out more than 130 scholarships totaling $332,500, all earmarked for students planning to continue career and technical educations after they graduate from high school. Bluebonnet also offers academic scholarships for students planning to attend four-year college and universities. (See story, facing page)

Recent visits to five high schools within Bluebonnet’s 3,800-square-mile service area offer glimpses into classrooms where students are learning skills for an array of careers.

Del Valle High School

Del Valle High School’s career and technical education program is expansive and impressive. It has 22 four-year career programs, and about 80% of the high school’s 3,400 students are enrolled in some career or technical sequence of classes.

Students in the southeastern Travis County school can choose from 34 industry-based certifications while in school, from graphic design and animation to finance to construction management.

In addition to these, Del Valle ISD has two other career-based high school paths. Early College High School allows a student to earn a high school diploma and an Austin Community College associate degree simultaneously. The Pathways in Technology program is another partnership with both ACC and area businesses to train students in advanced manufacturing or cybersecurity while they complete high school, plus earn a certification and/or an associate degree.

At Del Valle High School, many of the classrooms are nontraditional. Some replicate medical labs complete with computer-programed mannequins that simulate patients and can mimic symptoms of illness. There’s a mock ambulance, too. The welding teaching area includes a large assortment of equipment and tools, including welders, pipe cutters, grinders and every machine in between. Graphic design classes are full of both computers and examples of student projects — including designs for mini cereal boxes, re-imagined record covers and mock-ups of new sneakers. Students can even work on their personal cars in the school’s fully equipped auto mechanic shop.

J. Norris Sebastian III, director of career and technical education at the high school, said that about eight years ago the school district reorganized classes and areas of study to bring a more comprehensive approach to the career and technical program.

Sebastian, a former executive chef, believes the culinary arts graduates — who in high school learn to manage a kitchen, plan events and manage projects — will be able to begin a job with some seniority and higher pay.

Jocelyn Rosales, a 2021 graduate of the school’s culinary arts program, is studying event planning at ACC. What she learned in high school helped her get through the first year of college. “The teachers (at Del Valle) helped me push through and follow my dreams. They convinced me to jump out of my little bubble. And I did,” Rosales said.

Other Del Valle culinary arts graduates have also gone to ACC and the University of Houston, said instructor Ashley Jenkins. Students in Houston can go on to earn a bachelor’s degree in global hospitality leadership or a doctorate in hospitality administration.

Lockhart High School

Traffic crashes happen. If a vehicle collision occurs in Lockhart in Caldwell County, it’s possible that the person repairing the car or truck involved was a graduate of Lockhart High School’s 12-year-old collision repair program.

Students who finish the four-year course of study can work in the repair field immediately or soon after graduation. First-year students start with the basics of collision repair, then move to repair work in their second year. Juniors study paint and refinishing, and seniors put that knowledge to work as interns at auto body shops in Lockhart.

AJ Hernandez, the school’s collision repair teacher since 2015, is proud of the program he has developed. “Students can go directly into the collision repair industry with the certifications they have earned. They can also go to tech school to get more knowledge and practice,” he said.

Program graduates receive Level 1 certification in professional body repair work, based on industry standard ratings. To advance in the field and reach higher levels, students typically continue their education at schools where collision repair courses are an area of focus, such as Universal Technical Institute in Houston or Austin, or at ACC.

Instructor Hernandez’s son, junior Blayn Hernandez, is in his third year of the program. His goals beyond high school aren’t focused on collision repair, though. Hernandez wants to enter the medical field and eventually become a surgeon. He takes other classes to further that goal, but why collision repair? “One of the things we do in collision is wrap cars or different objects” in a vinyl film that requires intricate cuts, he said. “Very intricate cuts are made in surgery as well.”

In one recent class, third-level juniors learned to repair plastic bumpers, a skill requiring precision. Careful sanding is followed by melting new plastic at a high temperature, then seamlessly smoothing it into the sanded groove. The work is repeated on the bumper’s flip side.

Right now, all five seniors in the program work as interns at Caliber Collision in Lockhart. It is their practicum, the final level of training in high school.

“Not including our first-year basic class, we have about 70 students in collision repair and paint and refinish,” Hernandez said.

About 93% of Lockhart High’s 1,969 students are in career and technical education courses. Students can choose from 16 focus options within the programs, including introductory courses in accounting and finance, as well as various certifications such as in emergency response.

Rachel Sotelo, the school’s career and technical education coordinator, said those students “can graduate with an industry-based and recognized certification. They are able to walk right into their career or pursue post-secondary education.”

Giddings High School

Welding, agriculture sciences and business are among the most popular classes in the career coursework at rural Giddings High School in Lee County.

The 643-student high school has seven career and technical “clusters,” according to interim principal Karla Sparks. Those groupings are business/marketing/finance, human services, STEM (science, technology, engineering and math), agricultural/food/natural resources, manufacturing, teaching/learning and cosmetology.

Greg Morris, the school’s welding teacher, says there are more jobs available in the welding field than there are students able to complete the rigorous four-year program.

Welding students are expected to work hard, consistently improve their skills and undertake projects for the community. The program requires a time commitment that some students aren’t able to meet, Morris said. Students who complete the welding courses can earn certifications and more easily get a job after high school.

Billy Roschetzky, a senior, plans to continue learning after high school. “I am going to Tulsa Welding School in Houston in July after I graduate,” he said. “I’m not sure what I want to study specifically, but probably structural and fabrication,” the art of building metal products from scratch.

Roschetzky tried his hand at welding before taking the high school classes, but Morris’ classroom is where he fell in love with the process. “I am surprised with how much technique it takes to be a good welder,” he said.

Morris is popular among his students. Taylor Wells, a junior who has been in welding classes for two years, said his teacher is the best part of the course: “He is patient and helps us learn what we need to know.” Wells has Level 2 welding certifications and plans to continue in the field after graduation.

After finishing the welding program, many students such as Roschetzky go on to specialty schools to become pipefitters, fabricators, general welders or fill another of the many jobs in the trade. The American Welding Society says the nation will need an additional 375,000 welders to satisfy industry needs by the end of this year. The industry is growing, and older generations are leaving the field. Welders in Texas don’t have to take prerequisite courses, but certification usually requires some training.

Brett Schneider graduated from Giddings in 2021 after taking all of Morris’ courses and, with the teacher’s encouragement, went on to Tulsa Welding School. Today he is a structural welder at Perry & Perry Builders in Rockdale in Milam County, where he helps build large industrial buildings and other commercial structures.

Brenham High School

The students in Faith Gaskamp’s anatomy and physiology class at Brenham High School in Washington County didn’t seem too excited to start the day’s project: dissecting a preserved sheep’s brain. But even though they had the option to perform the lesson virtually, all of the students chose the hands-on experience.

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted more students at Brenham High School — and at schools nationwide — to focus on career- or technical-oriented coursework, said Gaskamp, who also teaches other health science classes. The high cost of attending college is a factor, but not the only one. “We have seen a return to the importance of trade-based programs,” she said. “Trades are the backbone of our society and students want to become a part of this change.”

The 1,500-student high school has six career paths. In the health science arena, students can obtain certification as medical assistants. Other certifications are for veterinary assistant, two levels of welding, floral “knowledge base” (focused on floral design), Microsoft Word and ServSafe food safety.

Classes for the health science track at Brenham are full, with 25 students in each, and they are expected to grow, because of student interest along with state requirements for career study coursework.

With courses in anatomy and physiology, pathophysiology and medical terminology, students studying health sciences should be well-equipped to become medical assistants. They can also continue studying to earn other medical-related certifications or obtain degrees at two- or four-year colleges.

In Texas, there is a shortage of medical assistants. That creates more work for existing office staff and can affect the number of patients who can be treated, according to the Texas Medical Association. Medical assistant is the most difficult position to fill because certified medical assistants have many opportunities for higher paying jobs elsewhere, the medical society reported in December 2022.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of certified medical assistants is projected to grow nationwide by 5% in the next eight years.

“Most of the students in the health sciences pathway attend some type of schooling or additional certification program after graduation . . . specializing in a health pathway they are passionate about,” Gaskamp said.

Cheyann Nugent, a junior on the health science track, said she enjoys “learning how the body works, especially the brain.” She is getting plenty of hands-on experience at Brenham High. “We do a dissection or lab at the end of every unit. We are about to dissect a lamb’s eye,” she added. Nugent plans to receive her medical assistant certification when she graduates in May 2024.

Somerville High School

Teachers in the agriculture program at Somerville High School in Burleson County pride themselves on offering practical educations and skills to students in this rural community. Programs include turf management, plant soil science, floral design, and fabrication, which includes welding and construction.

“We hope that when students leave our ag program they have a better knowledge of where their food comes from, how it is raised, harvested and processed for consumption,” said Greg Moore, an agriculture teacher.

Out of the 205 high school students at Somerville High, 85%, are enrolled in agriculture classes.

Agriculture is more than “cows, sows and plows,” Moore said. It is also about science, genetics and learning how to meet the demand for livestock while the interest in raising it is waning. “The ag industry has changed so much in the last ten years with the increased use of drone, GPS and additional technologies. I stress the importance of studying science along with agriculture,” he said.

This might be one reason he has seen a big change in his classroom in the last few years: Young people who do not fit the mold of “traditional” agriculture-studies students are joining his classes.

Nontraditional ag students are typically those who don’t show animals or participate in the school’s chapter of the Future Farmers of America. One of these students, Grace Casas, found herself in the agriculture program when she took the floral design class. However, she doesn’t foresee a career creating artistic floral arrangements. Casas plans to study for certification as an ultrasound technician when she graduates in May.

A student in the traditional ag student category, Natalie Shupak, has raised and shown pigs for the last few years. She has taken welding, landscape design and floral design classes and participates in FFA. But she wants to get a business degree and open a retail boutique when she graduates.

Elsewhere, in turf management classes, a favorite class project is to create a “stadium in a box.” Students grow their own grass, maintain it and create whatever type of sporting field they want in the boxes made from woodshop project scraps. Students have made baseball and soccer fields, and last year, one student made a food truck park.

While Moore and his welding and construction instructor colleague, Jonathan Meurin, encourage students to pursue their passions when considering education and careers, students often choose to stick with what they learn in class. Moore’s strategy of pairing agriculture with science and teaching the connection between them allows students to consider nontraditional agriculture careers.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts 9% growth in jobs for technicians in agriculture and food science. Somerville students who want to follow the career paths taught in Moore and Meurin’s classes must first take principles of food and natural resources. The teachers believe it is essential that students understand food sources and issues associated with that before they move ahead.

“Students have more awareness of where their food comes from and how it gets to the table. Because of this, our students are more aware of the opportunities that are available,” Moore said. “The world we know today will not be the same tomorrow, and the agriculture industry has to grow and change to meet those needs in producing food, fiber and construction materials.”

***

What trade careers make top pay?

The highest paid in-demand trade jobs are typically in the construction, health care, energy or engineering industries. The jobs are often specialized and many require significant training, certifications, licensing and, sometimes, experience. Annual salaries (nationwide) include:

- Construction manager, $108,210

- Nuclear technician, $99,340

- Radiation therapist $82,790

- Commercial driver, $82,010

- Electrical line worker, $79,060

- Dental hygienist, $77,810

- Website developer, $77,200

- Building inspector, $68,480

- Respiratory therapist, $68,190

- Power plant operator, $67,565

Other trade jobs that earn, on average, $60,000 or more annually include aircraft mechanic, real estate appraiser, electromechanical technician, elevator mechanic, industrial mechanic, electrician, plumber, boilermaker, construction inspector and landscape designer.

Health care trade jobs that are in demand and high on the list of annual pay include ultrasonographer, MRI technologist, surgical technician, occupational therapy assistant, physical therapy assistant and dental assistant.

Sources: Money.com (2022), equipmentandcontracting.com (2022), LinkedIn.com (2021)

***

Keep on learning

TRADE AND TECHNICAL SCHOOLS, COLLEGES IN THE REGION

Numerous programs, schools and specialized colleges in Central Texas offer training programs through which high school graduates can obtain certifications and degrees in many trade and technical fields. Among the largest that offer in-person, online or hybrid-learning options are:

TEXAS STATE TECHNICAL COLLEGE, with campuses in Waco, Austin and Hutto, has more than 40 programs and degrees in a variety of industries; in-person and online coursework; information online at tstc.edu/programs/

BLINN COLLEGE’S APPLIED TECHNOLOGY, WORKFORCE AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT programs offer certifications, associate of applied science degrees, industry credentials and continuing education courses at multiple campuses, including in Brenham and Bryan. Blinn’s A.W. Hodde, Jr. Technical Education Center in Brenham partners with local school districts and industries to offer training; information at blinn.edu/workforce/ and search on the site for the A.W. Hodde, Jr. Technical Education Center.

THE TEXAS A&M ENGINEERING EXTENSION SERVICE offers programs in fire and rescue, infrastructure and safety, law enforcement, economic and workforce development and homeland security; find a list of certificate programs and information at teex.org/certificate-programs/

AUSTIN COMMUNITY COLLEGE offers numerous programs ranging from computer science & IT, education and health sciences, as well as certifications in fields including welding, HVAC, plumbing; learn more online at continue.austincc.edu/career-and-technical

UNIVERSAL TECHNICAL INSTITUTE TRADE AND VOCATIONAL SCHOOL in Austin (with other campuses in Houston and Dallas/Fort Worth) has training in automotive, diesel, HVACR and welding industries; more online at uti.edu/locations/texas/austin

THE COLLEGE OF HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONS offers numerous programs in the health care field at multiple campuses in Texas, including Austin, San Antonio and Houston, as well as some online programs; information at chcp.edu

RESOURCES

THE TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD reviews and approves career and applied technical degrees, and workforce certification programs at community, state and technical colleges; highered.texas.gov/our-work/equipping-our-workforce/

THE TEXAS WORKFORCE COMMISSION licenses career schools and colleges, provide resources and a list of all accredited schools and colleges; twc.texas.gov/jobseekers/career-schools-colleges-students

This fierce sea creature’s skeleton, spotted a century ago by students, returns to limited public display this year.

By Denise Gamino

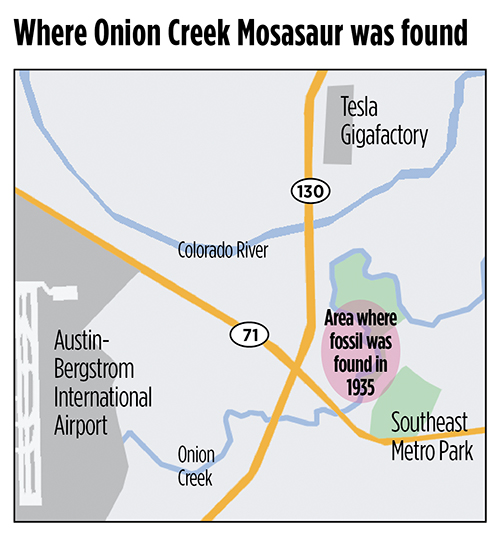

Elon Musk and the Tesla Gigafactory may be the biggest recent sensations in eastern Travis County near the Colorado River, but about 66 million years ago, a truly jaw-dropping phenomenon roamed that area.

SEE THE DINOSAUR PICTURE AND DRAWING SUBMISSIONS

Meet the immense sea creature that got to Texas ages before anyone else.

MORE DINOSAUR SITES IN TEXAS

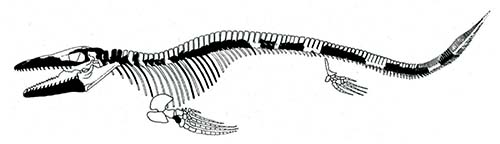

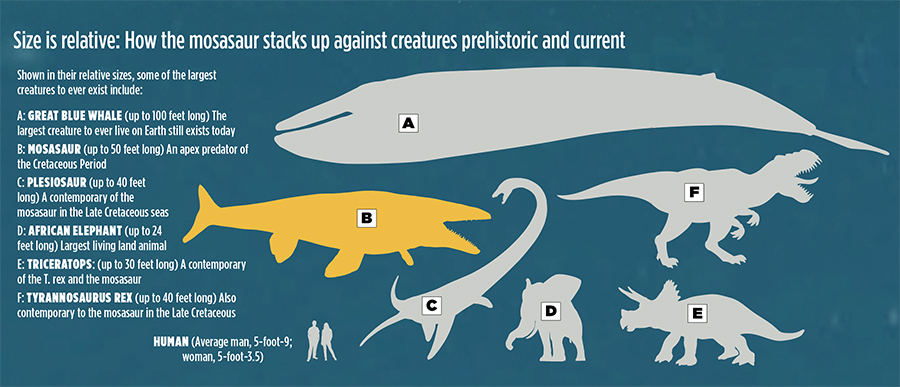

The Onion Creek Mosasaur was a ferociously aggressive 30-foot marine reptile that lived during the dinosaur age. Its 3-foot-wide open mouth and 4-foot-long jaw made it the top predator — and largest animal — in the inland sea that covered much of Texas and 40% of present-day North America millions of years ago. The voracious mosasaurs, swimming in water as deep as 600 feet, “would eat pretty much anything which could fit into their enormous mouths — which, it turns out, was a lot,” according to the National Park Service. Its diet included sharks, fish, birds, ammonites (extinct mollusks) and even other mosasaurs.

The menacing mosasaur (MOSE-uh-sawr) skeleton is the preeminent display at the Texas Memorial Museum on the University of Texas at Austin campus. The museum was closed to the public almost a year ago because of budget cuts, but new funding has allowed behind-the-scenes work to continue. The museum is scheduled to reopen in stages, beginning this fall. The Onion Creek Mosasaur will be seen from afar by visitors at that time, but the public would be allowed a closer inspection of the mosasaur when the second phase of the museum’s reopening occurs in the spring of 2024.

Texas Memorial Museum’s website describes the Onion Creek Mosasaur skeleton as “spectacular.” It’s believed that geologists first saw a part of the giant fossil 100 years ago near present-day Texas 71 and Onion Creek, but the nearly complete skeleton was found there in 1935 by fossil-hunting UT geology students. Those students graduated and went on to have prominent careers in the oil — a fossil fuel — industry.

No one knows whether other petrified mosasaurs may be buried in that area, possibly now covered by roads or buildings. Unlike the federal government, Texas does not require a paleontology review before construction projects begin.

But for at least a century, the area of Onion Creek near today’s Travis County Southeast Metropolitan Park has been known as such a “fossiliferous,” or fossil-rich, spot that it became a favorite specimen-hunting site for UT geology professors and their students. Most finds were oyster shells, clams and other fossilized seashells.

Mosasaurs existed in the Late Cretaceous Period, which geologists believe ended violently about 66 million years ago when an asteroid about 6 miles wide slammed into what is now the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico, causing an enormous inferno and a deadly planetwide dust cloud. The impact is thought to have been as powerful as 10 billion atomic bombs of the type used in World War II. The result was the mass extinction of all dinosaurs (except the forerunners of today’s birds), as well as ocean creatures such as mosasaurs, ammonites and plesiosaurs.

Millennia after that extinction event, on a Saturday afternoon in the fall of 1935, sophomore UT geology students W. Clyde Ikins, from Weatherford west of Fort Worth, and John Peter “Pete” Smith, from Dallas, made the 14-mile trip from the UT campus to the fossil-hunting site on Onion Creek. They were looking for fossilized marine oysters, a common specimen to the area, to fulfill a laboratory assignment.

“We had gone about a quarter of a mile north of the highway bridge on the east bank of the creek when we discovered some bones sticking out of the bank near the water level,” Ikins wrote to UT in the mid-1960s. “We found several vertebrae, rib bones, and a section of the jaw bone about two feet long. The jaw was complete with the large teeth which were used to crush mollusks. The teeth were so well preserved that they had their original polish and luster. At this stage we were very impressed with our find, but had no idea that it would turn out to be probably the most complete mosasaur skeleton that has been found to date.”

Smith was equally proud. “We got a great thrill out of the find as I had been hoping to find one since the day that Dr. (Robert) Cuyler (associate professor of geology) took us on our first Geology 1 field trip,” he wrote in a 1967 letter to UT. “He mentioned that they (mosasaurs) were around, it just took time to find them.”

Ikins and Smith dug out several mosasaur bones that day and brought them back to UT.

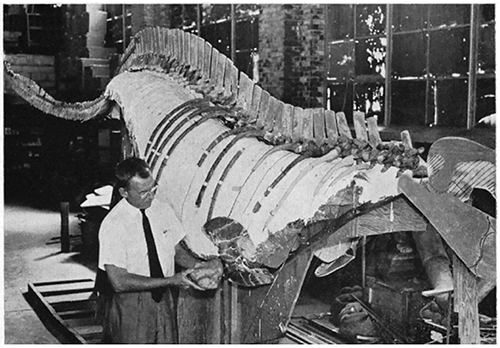

University geology officials were beyond elated by the rare discovery. The prized bones were found just in time to be excavated and showcased in UT’s Gregory Gymnasium as part of a statewide extravaganza to celebrate the 1936 Texas Centennial. They also hoped the mosasaur would bring public and scientific enthusiasm for the Texas Memorial Museum, then in the planning stages. It would open in 1939.

UT’s 1936 Centennial Exposition featured an array of Texas natural science exhibits — such as dinosaur tracks and anthropology dioramas — that drew visitors from all over Texas as well as every other state and 39 countries. The expo ran from June through November 1936, and then cleared out for UT basketball season. It was so popular that visiting hours had to be extended to accommodate the crowds, who could watch the mosasaur bones (except for the skull) being cleaned, preserved and readied for display.

The Onion Creek Mosasaur skeleton “is a particularly lucky find because the specimen is perfect,” noted the late H.B. Stenzel, a geologist who directed the 1936 excavation for UT’s Bureau of Economic Geology, the university’s oldest research unit. His comments were included in a June 7, 1936, UT press release about the Centennial Expo. “With careful supervision, we will have the most perfect specimen of mosasaur yet found in the world.”

Unfortunately, a calamity at the end of the expo delayed the mosasaur’s full public debut at the Texas Memorial Museum for several decades. Workers moving the mosasaur skeleton dropped it, and the bones shattered into many pieces and small fragments. “It remained in this condition for years and years,” Ikins wrote in his mid-1960s letter to the Texas Memorial Museum. “I think the only part of the skeleton that remained in any recognizable form was the head.”

The mosasaur remained asunder until the 1960s, when notable paleontologist Wann Langston, Jr. arrived at UT. He began a two-year process of reassembling the mosasaur skeleton and reconstructing some missing parts so the entire thing could finally be put on public display.

“The paleontologist and preparator reassembled all parts of the skeleton in a natural (swimming) position,” Langston wrote about the mosasaur in a 1966 detailed scholarly study for the Texas Memorial Museum. “As is usual with fossils, some parts of the Onion Creek Mosasaur had been lost before the skeleton was buried and some bones were destroyed by weathering before the discovery was made,” Langston wrote.

“Missing parts were molded in plaster and assembled in their appropriate places among the original bones. These included most of the paddle bones, some vertebrae, ribs, and various parts of the skull and jaws.”

The mosasaur quickly became the museum’s top exhibit when it went on display in the mid-1960s. Ten years later, UT learned that the university’s connection to the mosasaur was older than previously thought.

In 1975, former UT geology student L.T. “Slim” Barrow, the retired board chairman of Humble Oil and Refining Co. (later to become Exxon), sent a letter of congratulations to UT for, among other things, “the perfect job” of reassembling the mosasaur. He said he had been among a group of UT geology students in 1923 or 1924 who had seen some of the mosasaur’s vertebrae at Onion Creek. The students began to dig, Barrow wrote, but “we realized it was too big a job for us and quit before we had done any damage.” Twelve years later, Ikins and Smith found the nearly complete skeleton.

The Onion Creek Mosasaur was far from the only mosasaur that swam the Cretaceous waters that covered much of what is now Texas, while dinosaurs roamed on land. "Fossilized parts of several mosasaur species have been collected from roughly 100 spots in Texas,” said paleontologist and geologist Chris Sagebiel, the current collections manager of UT’s Texas Vertebrate Paleontology Collections. “However, most sites produce only one tooth, or only a bone or two.”

Western Kansas is a hot spot for mosasaur fossils, ranging from single bones to nearly complete skeletons. In Texas, similar “chalk deposits and associated limestone and shale are exposed in a narrow band extending from northeastern Texas (Red River and Bowie counties) southwestward to San Antonio, and westward toward the Big Bend,” Langston wrote in 1966.

“Dallas, Waco, and Austin are all built on these rocks, and mosasaur bones have been found in them, especially in Dallas, McLennan, Williamson, Travis, and Hays counties.”

In 2022, an amateur fossil hunter discovered part of a mosasaur skeleton in the streambed of the North Sulphur River 80 miles northeast of Dallas. Paleontologists from the Perot Museum of Nature and Science in Dallas excavated parts of the fossilized skull, lower jawbone and vertebrae, and plan to continue excavation work.

The exact location of most fossil sites is protected information, and is even exempt from freedom of information laws to preserve them from commercial hunters or vandals, UT’s Sagebiel said. However, the location where the Onion Creek Mosasaur was found is no longer secret because it has been destroyed over the decades by construction on the Texas 71 bridge over Onion Creek. “I believe that the actual (mosasaur fossil) site has since been thoroughly excavated, demolished and concreted over,” he said.

Even with the Onion Creek Mosasaur’s last resting place no longer accessible, Texas still has plenty of ancient creature fossils yet to be found. In fact, the “most fossiliferous site in Texas” is in another part of Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative’s service area, according to the American Federation of Mineralogical Societies. That is a spot along the Brazos River in Burleson County, where a huge deposit of marine fossils includes the remains of snails, oysters, clams and shark teeth.

Collectors have hunted for centuries at that fossil site, under the Texas 21 bridge northeast of Caldwell. Texas A&M University students and science groups still make regular field trips there.

The Brazos Valley Museum of Natural History in Bryan features fossils from the Museum of the A&M College of Texas, which closed in 1965. The Brazos Valley Museum’s collection includes ice age and dinosaur age and casts, including skulls of a mastadon, a triceratops and a Tyrannosaurus rex.

But Texas’ biggest paleontology finds have been made in the Big Bend area of far West Texas. A Texas Pterosaur, with a wingspan of almost 40 feet, was found in that region. You will be able to see its reconstructed skeleton soar in the Great Hall of the Texas Memorial Museum when it reopens in the fall.

***

From fossils to fossil-fuel careers

L. T. ‘SLIM’ BARROW Barrow, who spotted some of the Onion Creek Mosasaur bones in 1923 or 1924, was a native of Manor and played football and basketball for the Longhorns while studying geology. Humble Oil and Refining Company (now Exxon) hired him as a field geologist for surface geologic mapping in Caldwell and Guadalupe counties, where Humble discovered the Salt Flat and Darst Creek oilfields, according to the Texas State Historical Association. He became Humble’s chief geologist in 1929 and rose to chairman of the oil company’s board in 1948. He helped establish a memorial endowment to UT’s Geology Foundation in the late 1950s, in honor of one of his former professors. Barrow died in 1978.

W. CLYDE IKINS One of two UT geology students who found the nearly complete skeleton in 1935, Ikins studied chemistry, botany and geology at UT, earning a doctoral degree in geology. He began his geology career with the Black Mesa Mining Company exploring for brilliant red cinnabar (mercury ore) in Terlingua, near today’s Big Bend National Park. He became chief geologist for Dow Chemical, and later president and CEO of Hondo Petroleum. His botany interests were focused on waterlilies, irises, cacti and succulents. In 1981, he donated his sweeping cacti and succulent collection gathered from around the world to his botanist friend, Dr. Barton Warnock, for a botanical garden in the Big Bend area. Ikins became one of the world’s foremost experts on water lilies and irises. He died in 2005, but today, the peony-like “Nymphaea Clyde Ikins” water lily is still available for sale.

JOHN PETER ‘PETE’ SMITH Smith, along with Ikins, found the nearly complete skeleton in 1935. He went on to become the exploration manager for Esso (Standard) oil’s Libya division and was based in Tripoli. Esso was owned by Standard Oil and became Exxon in 1972. Esso was famous for an ad that encouraged drivers to “put a tiger in your tank” with Esso Extra premium gasoline. Smith retired from Standard Oil in 1967.

History on hold

The Texas Memorial Museum of science and natural history began, appropriately, with a big bang. In June 1936, President Franklin D. Roosevelt set off the dynamite that broke ground for the museum on the University of Texas campus in Austin. Roosevelt, who was on a presidential campaign train trip across Texas, remained on his parked passenger train near present-day East Fourth Street and Interstate 35 while pushing a big red, remote-control button to blast the limestone. The museum temporarily closed to the public in March 2022 because of a staff shortage. However, with university support and fundraising efforts, staff are renovating the museum to open in stages, beginning in September. The Onion Creek Mosasaur will be on display — from a distance — when the museum reopens, but visitors will not be able to get close to it until the second phase of reopening in spring of 2024. The museum is at 2400 Trinity St. in Austin. — Denise Gamino

Meet the Onion Creek Mosasaur!